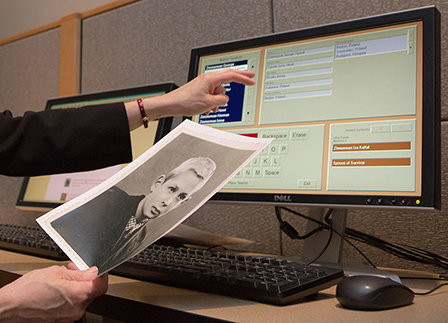

Johanna (Hanne) Eva Hirsch was born on November 28, 1924, in Karlsruhe, Germany, to Jewish parents, Max and Ella. Max was a photographer and operated a photographic studio. When Max died in 1925, Elle continued to operate the studio. In 1930, Hanna entered the public elementary school. In January 1933, Hitler became Chancellor of German and anti-Jewish repressions intensified throughout the country. The Hirsch studio and other Jewish businesses in Karlsruhe were covered with signs telling people not to use Jewish stores. Hanne was taunted by classmates for being a Jew and, once, became so angry she ripped the sweater of her tormentor. Ironically, the photo studio had an upsurge of business after the November 9-10 Kristallnacht pogrom as Jews were required to get new identification cards marked “J” for Jew. The studio and all other Jewish businesses were ordered to shut down on December 31, 1939.

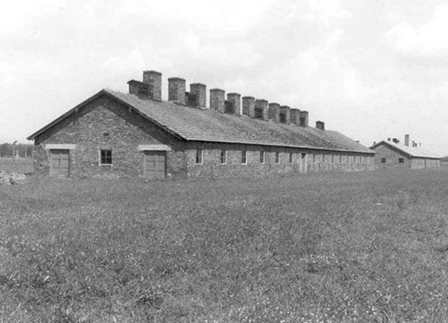

In October 1940, Hanne and Ella were deported to Camp de Gurs in Vichy France near the Spanish border. While in the camp, Hanne met Max Liebmann, born in 1921 in Mannheim, Germany, who had been deported to Gurs with his mother on October 22, 1940. Hanne heard about a pastor in the nearby village, Le Chambon, who helped get children out of the camp. He worked with a Jewish rescue agency, Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants (OSE/ Aid to Children). In September 1941, OSE rescued Hanne from Gurs where they had begun to deport prisoners to the concentration camps in Poland. Hanne was hidden in a children’s' home in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon run by Albert Bohny. By 1942, the Germans were beginning to round-up Jews in the southern countryside and Hanne was placed in hiding on two different farms, whose owners generously shared what they had with the refugees.

In 1943, Hanne obtained false papers in Le Chambon as a French girl and the underground arranged to help her get to Switzerland where she had a maternal aunt. With an escort from the underground, Hanne journeyed by train from Lyon to Annecy, and then walked from there to Annemasse where her papers were examined by a customs officer who asked her if she was Jewish. She denied being a part of the ‘dirty race” and with a slight smile, he let her continue. She was supposed to stay in a convent, but they decided not to take her in. Her escort found her lodging for the night and the next morning went with her to the convent and the nuns then helped her get to Tourneau. A priest hired by her uncle then guided her across the Swiss border with a group of other Jews on February 23. She lived for a while with her uncle, aunt, and cousin and attended school until she became ill with pneumonia. For a while, she worked on a farm as part of a Swiss program that drafted teenagers to work with farmers. Hanne had been classed as an emigrant, thus was able to move around to various cities and obtain employment. She had to renew her visa every six months and would be interviewed and asked when she expected to leave Switzerland. In 1944, she moved from Bern to Geneva where she worked as a household maid and boarded with some Bulgarian refugees. She re-encountered Max Liebmann, who was there on a pass from a refugee internment camp to take a social work course.OSE had also rescued Max from Gurs in July 1942 by placing him at a farm operated by orthodox French-Jewish Boy Scouts. When the Germans raided the camp in August 1942, Max escaped to Le Chambon-sur-Lignon. He hid there for four weeks, then with false identity papers, fled over the Alps to Switzerland.

Hanne and Max married in Geneva on April 14, 1945. The couple had a daughter in 1946. They learned that Johanna’s mother had been deported and murdered in Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland. Max’s mother and father met a similar fate. Hanne’s brother, who had emigrated ot the US in 1937, had joined the US Army and been killed in the Battle of the Bulge. In 1948, a cousin in the US provided an affidavit of support and the couple emigrated to the United States. The Swiss would not permit Max to withdraw his money from the bank. He consulted a lawyer who could withdraw it for him, and the lawyer chose to pay for their journey himself. In 1952, the Swiss finally released his money to Max.