Overview

- Brief Narrative

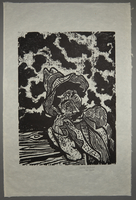

- Woodcut portrait of a Sinti woman created by Otto Pankok, a German artist persecuted by the Nazi regime. In the 1920s, he was part of the avant garde Junge Rheinland group with Otto Dix, Gert Wollheim, Karl Schwesig, and Adolf Uzarski. Around 1930, Pankok became fascinated by the itinerant life led by Roma and Sinti, and exhibited his first series of portraits in 1932 at the Dusseldorf Kunsthalle. Under the Nazi regime which came to power in 1933, art and culture had to serve to promote national socialist ideology. Modern art was denounced as a tool of the international Jewish conspiracy. In 1933, some works from Pankok's Passion Cycle, which reimagined the Passion of Christ in a national socialist state, with Communists, Jews, Roma, and artists as the pure and good, and the Gestapo and other Nazis as the evil and fallen. It was soon shut down by the government. In 1935, Pankok was investigated by the Gestapo. After a book of the Passion Cycle was published in 1936, Pankok was designated a degenerate artist and forbidden to work as an artist. His works were removed from museums and one of his Sinti lithographs, Hoto II, was included in the 1937 Entartete Kunst [Degenerate Art] exhibition. In spite of this, Pankok continued working in secret to create artwork depicting Communists, Jews, Roma, and others who suffered under the Nazi regime. After the war, he again was a professor at the Art Academy in Dusseldorf.

- Artwork Title

- Dinili

- Date

-

creation:

1948

issue: 1960

- Geography

-

creation:

Dusseldorf (Germany)

issue: Wesel (Germany)

- Credit Line

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection, Gift of Eva Pankok

- Contributor

-

Artist:

Otto Pankok

Subject: Otto Pankok

- Biography

-

Otto Pankok was born on June 6, 1893, in Saarn near Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany, to Dr. Eduard and Marie Spring Pankok. Otto had an older brother, Adolf. His father had a medical practice. He graduated from the state school in 1912. Otto studied art at several school, the Academy of Fine Arts in Dusseldorf, the School of Fine Arts in Weimar and then went to Paris, where he attended the Academie Russe and the Academie de la grande Chaumière. When war broke out in 1914, Otto was conscripted into the Germany Army. He was wounded in a blast early in the war, hospitalized for months, and released from service in April 1917. The war ended in 1918. The next year, Otto moved to Berlin, then to Remels with his friend and fellow artist, Gert Wollheim. In 1920, both men moved to Dusseldorf. They worked with other artists, including Max Ernst, Otto Dix, Karl Schwesig, and Adolf Uzarski, as part of an avant garde group of intellectuals and artists known as Das Junge Rheinland [Young Rhineland]. They joined the Aktivisten-bund [Activist League] and were among the artists promoted by art dealer Johanna Ey (Mutter Ey), who exhibited their work in her gallery. In 1921, he married Hulda Droste, a journalist. Their daughter Eva was born on July 14, 1925. Pankok and the others sought an artistic language that was more modern and truthful, unconnected with existing social customs and structures. Pankok developed a monochromatic style, relying on strong, expressive lines and forceful composition. Pankok first worked primarily as a painter and printmaker, but in the late 1920s, he began creating sculptural work. Between 1927 and 1929, he traveled to Italy, southern France, Spain and Holland, and produced a series, Lithos. He achieved fame in 1930, for Stern and Blume [Star and Flower], a series of 130 works. His works were deeply influenced by his idol Vincent van Gogh, and his style was referred to as expressive realism. Around the same time, fascinated by the itinerant life led by Roma and Sinti, Pankok visited a number of Roma encampments in France and Germany. In 1931, he worked in an unemployment colony in Heinefeld, near Dusseldorf, where Sinti also camped. In October he created his first works in his Sinti cycle; a series of portraits of Sinti were exhibited in 1932 at the Dusseldorf Kunsthalle. In 1932, he began work on a cycle of sixty drawings, Die Passion.

In January 1933, Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany. Under the Nazi regime, art and culture had to serve to promote Nazi ideology. In September, Hitler announced that it was time for a new, pure German art. Modern art was denounced as degenerate, a tool of the international Jewish conspiracy. A few works from Pankok's Passion cycle were displayed in 1933. It reimagined the Passion of Christ in a national socialist state, with Communists, Jews, Roma, and artists as the pure and good, and the Gestapo and other Nazis as the evil and fallen. It was soon shut down by the government. In 1935, Pankok was investigated by the Gestapo after a house servant denounced him. In 1936, the book "Die Passion in 60 Bilder von Otto Pankok" was published by Gustav Kiepenheuer, Berlin. Pankok was designated a degenerate artist and forbidden to work as an artist. His works were removed from museums and one of his Sinti lithographs, Hoto II, was included in the 1937 Entartete Kunst [Degenerate Art] exhibition. In spite of this, Pankok worked in secret to create work depicting Jews, Roma, and others who suffered under the Nazi regime in drawings and prints. The family tried but were not able to leave for Switzerland. He hid many of his works with friends. They relocated to Eifel near the Belgian border where they were not so aggressively persecuted.

The Second World War (1939-1945) ended in May 1945 when Nazi Germany was defeated by the Allied powers. In 1946, Pankok moved from Eifel back to Dusseldorf. From 1947-1958, he was a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts there. He traveled often to France and Yugoslavia. After leaving the Academy, Pankok to Haus Esselt at Drevenack on the Lower Rhine, where he again began to work intensively with wood carvings. Pankok, 73, passed away on October 10, 1966, in Wesel. Today Haus Esselt houses the Otto Pankok Museum.

Physical Details

- Language

- German

- Classification

-

Art

- Category

-

Prints

- Object Type

-

Portraits (lcsh)

- Physical Description

- Woodcut portrait in black ink on wove paper of a young woman with wavy, shoulder length hair, long eyelashes, pronounced cheekbones, and slightly parted lips. Her eyes are wide and she looks intently ahead. She wears a speckled blouse. The artist’s name is printed at the bottom.

- Dimensions

- overall: Height: 38.000 inches (96.52 cm) | Width: 25.125 inches (63.818 cm)

pictorial area: Height: 26.000 inches (66.04 cm) | Width: 19.000 inches (48.26 cm) - Materials

- overall : wove paper, ink

- Inscription

- front, below image, pencil : Nachlaß Otto Pankok / Eva Pankok [Estate of Otto Pankok]

back, bottom left corner, pencil : H291

Rights & Restrictions

- Conditions on Access

- No restrictions on access

- Conditions on Use

- Restrictions on use. Donor explains in her letter of 1-3-94 that she doesn't have reproduction rights to the works. (see letter)

Keywords & Subjects

Administrative Notes

- Legal Status

- Permanent Collection

- Provenance

- The woodcut was donated to United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in 1994 by Eva Pankok, the daughter of Otto Pankok.

- Funding Note

- The cataloging of this artifact has been supported by a grant from the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany.

- Record last modified:

- 2022-07-28 18:22:24

- This page:

- http://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn8530

Download & Licensing

In-Person Research

- By Appointment

- Request 21 Days in Advance of Visit

- Plan a Research Visit

- Request to See This Object

Contact Us

Also in Otto Pankok collection

The collection consists of five Sinti woodcut portaits created by Otto Pankok in postwar Germany.

Date: approximately 1948

Otto Pankok woodcut of a Sinti man in a hat

Object

Woodcut portrait of a Sinti man, Papelon, created by Otto Pankok, a German artist persecuted by the Nazi regime. In the 1920s, he was part of the avant garde Junge Rheinland group with Otto Dix, Gert Wollheim, Karl Schwesig, and Adolf Uzarski. Around 1930, Pankok became fascinated by the itinerant life led by Roma and Sinti, and exhibited his first series of portraits in 1932 at the Dusseldorf Kunsthalle. Under the Nazi regime which came to power in 1933, art and culture had to serve to promote national socialist ideology. Modern art was denounced as a tool of the international Jewish conspiracy. In 1933, some works from Pankok's Passion Cycle, which reimagined the Passion of Christ in a national socialist state, with Communists, Jews, Roma, and artists as the pure and good, and the Gestapo and other Nazis as the evil and fallen. It was soon shut down by the government. In 1935, Pankok was investigated by the Gestapo. After a book of the Passion Cycle was published in 1936, Pankok was designated a degenerate artist and forbidden to work as an artist. His works were removed from museums and one of his Sinti lithographs, Hoto II, was included in the 1937 Entartete Kunst [Degenerate Art] exhibition. In spite of this, Pankok continued working in secret to create artwork depicting Communists, Jews, Roma, and others who suffered under the Nazi regime. After the war, he again was a professor at the Art Academy in Dusseldorf.

Otto Pankok woodcut of a Sinti woman in a striped dress

Object

Woodcut portrait of a Sinti woman in a striped dress, Kitzla, created by Otto Pankok, a German artist persecuted by the Nazi regime. In the 1920s, he was part of the avant garde Junge Rheinland group with Otto Dix, Gert Wollheim, Karl Schwesig, and Adolf Uzarski. Around 1930, Pankok became fascinated by the itinerant life led by Roma and Sinti, and exhibited his first series of portraits in 1932 at the Dusseldorf Kunsthalle. Under the Nazi regime which came to power in 1933, art and culture had to serve to promote national socialist ideology. Modern art was denounced as a tool of the international Jewish conspiracy. In 1933, some works from Pankok's Passion Cycle, which reimagined the Passion of Christ in a national socialist state, with Communists, Jews, Roma, and artists as the pure and good, and the Gestapo and other Nazis as the evil and fallen. It was soon shut down by the government. In 1935, Pankok was investigated by the Gestapo. After a book of the Passion Cycle was published in 1936, Pankok was designated a degenerate artist and forbidden to work as an artist. His works were removed from museums and one of his Sinti lithographs, Hoto II, was included in the 1937 Entartete Kunst [Degenerate Art] exhibition. In spite of this, Pankok continued working in secret to create artwork depicting Communists, Jews, Roma, and others who suffered under the Nazi regime. After the war, he again was a professor at the Art Academy in Dusseldorf.

Otto Pankok woodcut of a Sinti woman with freckles

Object

Woodcut portrait of a freckled Sinti woman, Raklo, created by Otto Pankok, a German artist persecuted by the Nazi regime. In the 1920s, he was part of the avant garde Junge Rheinland group with Otto Dix, Gert Wollheim, Karl Schwesig, and Adolf Uzarski. Around 1930, Pankok became fascinated by the itinerant life led by Roma and Sinti, and exhibited his first series of portraits in 1932 at the Dusseldorf Kunsthalle. Under the Nazi regime which came to power in 1933, art and culture had to serve to promote national socialist ideology. Modern art was denounced as a tool of the international Jewish conspiracy. In 1933, some works from Pankok's Passion Cycle, which reimagined the Passion of Christ in a national socialist state, with Communists, Jews, Roma, and artists as the pure and good, and the Gestapo and other Nazis as the evil and fallen. It was soon shut down by the government. In 1935, Pankok was investigated by the Gestapo. After a book of the Passion Cycle was published in 1936, Pankok was designated a degenerate artist and forbidden to work as an artist. His works were removed from museums and one of his Sinti lithographs, Hoto II, was included in the 1937 Entartete Kunst [Degenerate Art] exhibition. In spite of this, Pankok continued working in secret to create artwork depicting Communists, Jews, Roma, and others who suffered under the Nazi regime. After the war, he again was a professor at the Art Academy in Dusseldorf.

Otto Pankok woodcut of a Sinti man

Object

Woodcut portrait of a Sinti man created by Otto Pankok, a German artist persecuted by the Nazi regime. In the 1920s, he was part of the avant garde Junge Rheinland group with Otto Dix, Gert Wollheim, Karl Schwesig, and Adolf Uzarski. Around 1930, Pankok became fascinated by the itinerant life led by Roma and Sinti, and exhibited his first series of portraits in 1932 at the Dusseldorf Kunsthalle. Under the Nazi regime which came to power in 1933, art and culture had to serve to promote national socialist ideology. Modern art was denounced as a tool of the international Jewish conspiracy. In 1933, some works from Pankok's Passion Cycle, which reimagined the Passion of Christ in a national socialist state, with Communists, Jews, Roma, and artists as the pure and good, and the Gestapo and other Nazis as the evil and fallen. It was soon shut down by the government. In 1935, Pankok was investigated by the Gestapo. After a book of the Passion Cycle was published in 1936, Pankok was designated a degenerate artist and forbidden to work as an artist. His works were removed from museums and one of his Sinti lithographs, Hoto II, was included in the 1937 Entartete Kunst [Degenerate Art] exhibition. In spite of this, Pankok continued working in secret to create artwork depicting Communists, Jews, Roma, and others who suffered under the Nazi regime. After the war, he again was a professor at the Art Academy in Dusseldorf.