Overview

- Brief Narrative

- Blanket issued to Ernst (Ernest) Heppner in Shanghai, China, by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) in August 1945. Ernst was living in Breslau, Germany (now Wroclaw, Poland), with his parents, Isidor and Hilda, his half-sister, Else, and near his half-brother, Heinz. Following the Kristallnacht program in November 1938, and Heinz’s subsequent arrest, the family began looking at emigration options. Eighteen-year-old Ernst and his mother secured passage on a ship to Shanghai, China, where they arrived in March 1939. Ernst soon got a job working for a toy store branch located inside a bookstore, where he began to learn reading English. He also joined an established British Boy Scout troop, the Thirteenth Rovers, and the Shanghai Volunteer Corps (SVC), which reinforced the International Settlement’s municipal police. In May 1943, the Japanese occupation authorities forced the stateless refugees into a ghetto in Hongkew. In April 1945, Ernst married Illo Koratkowski, an immigrant from Berlin. The following month, Germany surrendered to the Allies; Japan surrendered in August. Ernst and Illo were able to get civilian jobs with the American Army, and moved to Nanking (now, Nanjing) in 1946. The following year, Ernst, Illo, his mother, and his father-in-law immigrated to the United States. The couple settled in New York City, where their daughter was born. Ernst didn’t learn the fates of his family until after the war. Heinz and his family immigrated to England in 1939, but both Isidor and Else were killed in the Holocaust.

- Date

-

received:

1945 August

- Geography

-

received:

Shanghai (China)

- Credit Line

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection, Gift of Ernest G. Heppner

- Contributor

-

Subject:

Ernest G. Heppner

Issuer: United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA)

- Biography

-

Ernst Günther Heppner (later, Ernest Guenter,1921-2004) was born in Breslau, Germany (now Wroclaw, Poland), to Isidor (1878-c.1942) and Hilda (nee Liffmann, 1884-1982) Heppner. Ernst had two, older, half-siblings, Else (1905-1944) and Heinz (later Henry, 1907-2005). Isidor owned one of the largest matzah factories in Germany, and the family lived a comfortable, middle-class lifestyle. The family adhered to very conservative, almost orthodox religious practices. During the summers, Hilda and Else managed their family’s strictly kosher hotel in Altheide, a resort town near the Czechoslovakian border. Hilda traveled often to visit her large family, so Ernst spent much of his time with Else, who had contracted polio as a child and required leg braces and canes.

At his primary school in Breslau, Ernst was one of only two Jewish children in his class. He frequently experienced antisemitism from both teachers and other students, and got into many fights. Ernst was involved in a Jewish scouting group, which promoted paramilitary training and survival tactics. After completing primary school, Ernst was enrolled in a gymnasium (a college preparatory school). In 1933, Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor or Germany, and authorities quickly enacted anti-Jewish decrees that restricted every aspect of Jewish life. The family’s bank accounts were frozen. Ernst became ostracized at school, and was prohibited from participating with sports teams and class excursions. In 1935, the Nuremberg Laws were passed, mandating the total separation of Jews and non-Jews. Ernst was expelled from school, and his parents were forced to sell their hotel to non-Jews. Ernst began attending trade classes in welding and locksmithing, and became an apprentice at an industrial machinery company owned by a family friend.

On November 9 and 10, 1938, officials instigated pogroms against Jews and their property throughout Germany, known as Kristallnacht. The local synagogue was set on fire, but since Isidor’s factory was hidden from the street, it was spared. During the pogroms, 30,000 Jewish men were also incarcerated in German concentration camps. Ernst managed to hide from the SS officers who came through their neighborhood, while his father and brother were shielded at the factory. The following day, fearing threats against his wife and baby, Heinz surrendered for arrest, and was sent to Buchenwald concentration camp. His wife, Alice, managed to get him released a few weeks later.

The family began looking at emigration options. Else planned to immigrate to South America with her fiancée. Hilda’s niece, who lived in Washington, D.C., sent an affidavit for the family, but the lengthy quota list made immigration to the United States impossible. The only other place they could immigrate to without visas was Shanghai, China. Hilda secured a cabin for two on the Potsdam, and in early spring 1939, Ernst and Hilda took a train to Genoa, Italy, where they boarded the ship. Isidor needed to remain in Germany until he could sell the factory and their property, and until Else could leave as well.

Ernst and Hilda disembarked in Shanghai on March 28, 1939. Representatives from one of the Jewish committees met the new arrivals, and took them to a reception center and soup kitchen, where they remained for two weeks. Hilda quickly obtained a job as a caseworker for the Committee for the Assistance of European Refugees in Shanghai (CFA), assisting new refugees. This allowed Ernst and Hilda to rent a furnished room, rather than live in the overcrowded, primitive barracks in Hongkew, the Japanese-occupied district of the International settlement. Ernst soon made several new friends with whom he explored the city. That July, Ernst became ill with pneumonia and pleurisy, and was taken to a makeshift hospital run by the CFA. In August, Hilda received a letter from Heinz and his wife, Alice, who had been able to immigrate to England. They also received letters from various family members, including Isidor and Else, pleading for help.

Ernst got a job working for a Russian-Jewish family who owned a toy store. He was soon appointed manager of a branch located inside a bookshop. While there, Ernst began learning to read English. In late 1940, Ernst’s branch closed, and he began working for the bookseller, selling English-language books and office supplies. He also joined a British Boy Scout troop called the Thirteenth Rovers, with other older teenagers. As a Rover, Ernst helped organize a two-week camp experience. Ernst also joined the Shanghai Volunteer Corps (SVC) as a driver. The SVC was a militia under the command of British officers that reinforced the International Settlement’s municipal police. Though he had no prior driving experience, Ernst passed his test at the end of 1940.

In April 1941, Ernst met Illo Koratkowski (1923-2012), while helping to organize a charity ball. Illo had emigrated from Berlin in the spring of 1940, and worked for a rare-book dealer. That summer, Hilda left the CFA to work for the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC). After the December 7 attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese also bombed the British ships docked in the Shanghai harbor and occupied the city. British and American citizens were incarcerated in POW camps, and Ernst was forced to stop his activities with the SVC and the scouting group. It became illegal for those in the United States to send funds directly to Shanghai, so the support organizations ran out of money, and Hilde lost her job in April 1942. On November 18, Ernst and Hilda received their last letter from Else, which was sent from a Jewish home via the Red Cross.

On May 18, 1943, prompted by Nazi Germany, the Japanese forced the stateless refugees into a ghetto in Hongkew. Ernst and Hilda already lived within the borders, but couldn’t leave the ghetto without a pass. Ernst was forced to join an auxiliary police group, responsible for the self-protection of the ghetto, and became an assistant fire chief. He also began a new job at a bakery on the border of the ghetto, and received bread daily, as part of his wages. Hilda began operating a makeshift restaurant in their attic room.

Ernst and Illo married on April 8, 1945. On May 10, they learned of Germany’s surrender to the Allies. On July 15, American planes bombed the wharves near the ghetto. Two days later, military installations inside the ghetto were bombed. The collateral damage killed thousands and destroyed the bakery where Ernst worked. They continued to endure frequent air raids until Japan surrendered to the Allies on August 14. Soon after, the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) established offices and began distributing food, clothing, and medical supplies. Ernst and Illo were able to get civilian jobs with the American Army. In 1946, they were transferred to the Joint United States Military Advisory Group stationed in Nanking (now, Nanjing).

In the spring of 1947, Ernst received a message from his mother that their quota numbers for the United States had been called. On July 14, Ernst, Illo, his mother, and his father-in-law arrived in San Francisco. Ernst, Illo, and Hilda moved to New York City, while Illo’s father settled in Chicago. Illo quickly obtained a job with an import/export company in Manhattan. Ernst Americanized his name to Ernest and began working as a typewriter mechanic. Their daughter was born in July 1948, and the family moved to the Midwest in 1949.

Ernest did not learn the fates of his family until after the war. In April 1942, Isidor was deported to Kolomyja ghetto in German-occupied Poland, and likely died that year. Else was deported to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German-occupied Czechoslovakia in April 1943. In October 1944, she was deported on transport Et to Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland, where she was killed. Heinz and his wife settled permanently in England, where he changed his name to Henry. Henry was interned as an enemy alien on the Isle of Man, and released in April 1941. Ernest and Illo accompanied his mother during her move from New York to a retirement home in Basel, Switzerland in 1964. During that trip, Ernest reunited with his brother for the first time. Ernest became involved with the Anti-Defamation League, local survivor and Jewish groups, and civil rights activism. He also wrote an award-winning book documenting his war-time experiences.

The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) was an international relief agency representing 44 nations, but largely dominated by the United States. Founded in 1943, it became part of the United Nations (UN) in 1945, and it largely shut down operations in 1947. Its purpose was to "plan, co-ordinate, administer or arrange for the administration of measures for the relief of victims of war in any area under the control of any of the United Nations through the provision of food, fuel, clothing, shelter and other basic necessities, medical and other essential services." Its staff of civil servants included 12,000 people, with headquarters in New York. Funding came from many nations, and totaled $3.7 billion, of which the United States contributed $2.7 billion; Britain $625 million and Canada $139 million. The Administration of UNRRA at the peak of operations in mid-1946 included five types of offices and missions with a staff totaling nearly 25,000: The Headquarters Office in Washington, The European Regional Office (London), the 29 servicing offices and missions (2 area offices in Cairo and Sydney; 10 liaison offices and missions in Belgium, Denmark, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, Trieste; 12 procurement offices in Argentina, Brazil, Chile and later Peru, Cuba, India, Mexico, South Africa, Southern Rhodesia, Turkey, Uruguay, Venezuela; 6 offices for procurement of surplus military supplies in Caserta and later Rome, Honolulu, Manila, New Delhi, Paris, Shanghai), the sixteen missions to receiving countries (Albania, Austria, Byelorussia, China, Czechoslovakia, the Dodecanese Islands, Ethiopia, Finland, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Korea, the Philippines, Poland, Ukraine, Yugoslavia), and the Displaced Persons Operations in Germany.

UNRRA cooperated closely with dozens of volunteer charitable organizations, who sent hundreds of their own agencies to work alongside UNRRA. In operation only three years, the agency distributed about $4 billion worth of goods, food, medicine, tools, and farm implements at a time of severe global shortages and worldwide transportation difficulties. The recipient nations had been especially hard hit by starvation, dislocation, and political chaos. It played a major role in helping Displaced Persons return to their home countries in Europe in 1945-46. Its UN functions were transferred to several UN agencies, including the International Refugee Organization and the World Health Organization. As an American relief agency, it was largely replaced by the Marshall Plan, which began operations in 1948. [Source: UN Original finding aid of records of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA)]

Physical Details

- Classification

-

Furnishings and Furniture

- Category

-

Household linens

- Object Type

-

Blankets (lcsh)

- Genre/Form

- Blankets.

- Physical Description

- Green army blanket

- Dimensions

- overall: Height: 60.000 inches (152.4 cm) | Width: 90.000 inches (228.6 cm)

- Materials

- overall : wool

Rights & Restrictions

- Conditions on Access

- No restrictions on access

- Conditions on Use

- No restrictions on use

Keywords & Subjects

Administrative Notes

- Legal Status

- Permanent Collection

- Provenance

- The blanket was donated to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in 1989 by Ernest G. Heppner.

- Record last modified:

- 2023-08-24 13:46:47

- This page:

- https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn947

Download & Licensing

In-Person Research

- By Appointment

- Request 21 Days in Advance of Visit

- Plan a Research Visit

- Request to See This Object

Contact Us

Also in Ernest G. Heppner collection

The collection consists of scrip, badges, a blanket, a nightstick, documents, correspondence, publications, and other printed material relating to the experiences of the families of Ernest Heppner and Kurt Redlich in Europe and Shanghai, China, before, during, and after the Holocaust.

Date: 1929-1980

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 1 krone note, acquired by a Jewish refugee

Object

Scrip, valued at 1 krone, distributed in Theresienstadt (Terezin) ghetto-labor camp and acquired post-war by Ernst (Ernest) Heppner. Currency was confiscated from inmates and replaced with scrip, which could only be used in the camp. The scrip was part of an elaborate illusion to make the camp seem normal and appear as though workers were being paid for their labor, but the money had no real monetary value. Ernst was living in Breslau, Germany (now Wroclaw, Poland), with his parents, Isidor and Hilda, and his half-sister, Else, who was severely handicapped from contracting polio as a young child. He also had an older half-brother, Heinz (Henry), who lived with his wife and young child. Following the Kristallnacht program and Heinz’s subsequent arrest in November 1938, the family began looking at emigration options. Else planned to immigrate to South America with her fiancée. Seventeen-year-old Ernst and his mother secured passage on a ship to Shanghai, China, where they arrived in March 1939. Ernst and Hilda survived the war in Shanghai, and immigrated to the United States with Ernst’s new wife, Illo, in July 1947. Heinz and his family immigrated to England in 1939. However, Isidor and Else were unable to escape Germany. In April 1942, Isidor was deported to Kolomyja ghetto in German-occupied Poland, and likely died that year. Else was deported to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German-occupied Czechoslovakia in April 1943. In October 1944, she was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland, where she was killed.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 2 kronen note, acquired by a Jewish refugee

Object

Scrip, valued at 2 kronen, distributed in Theresienstadt (Terezin) ghetto-labor camp and acquired post-war by Ernst (Ernest) Heppner. Currency was confiscated from inmates and replaced with scrip, which could only be used in the camp. The scrip was part of an elaborate illusion to make the camp seem normal and appear as though workers were being paid for their labor, but the money had no real monetary value. Ernst was living in Breslau, Germany (now Wroclaw, Poland), with his parents, Isidor and Hilda, and his half-sister, Else, who was severely handicapped from contracting polio as a young child. He also had an older half-brother, Heinz (Henry), who lived with his wife and young child. Following the Kristallnacht program and Heinz’s subsequent arrest in November 1938, the family began looking at emigration options. Else planned to immigrate to South America with her fiancée. Seventeen-year-old Ernst and his mother secured passage on a ship to Shanghai, China, where they arrived in March 1939. Ernst and Hilda survived the war in Shanghai, and immigrated to the United States with Ernst’s new wife, Illo, in July 1947. Heinz and his family immigrated to England in 1939. However, Isidor and Else were unable to escape Germany. In April 1942, Isidor was deported to Kolomyja ghetto in German-occupied Poland, and likely died that year. Else was deported to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German-occupied Czechoslovakia in April 1943. In October 1944, she was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland, where she was killed.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 5 kronen note, acquired by a Jewish refugee

Object

Scrip, valued at 5 kronen, distributed in Theresienstadt (Terezin) ghetto-labor camp and acquired post-war by Ernst (Ernest) Heppner. Currency was confiscated from inmates and replaced with scrip, which could only be used in the camp. The scrip was part of an elaborate illusion to make the camp seem normal and appear as though workers were being paid for their labor, but the money had no real monetary value. Ernst was living in Breslau, Germany (now Wroclaw, Poland), with his parents, Isidor and Hilda, and his half-sister, Else, who was severely handicapped from contracting polio as a young child. He also had an older half-brother, Heinz (Henry), who lived with his wife and young child. Following the Kristallnacht program and Heinz’s subsequent arrest in November 1938, the family began looking at emigration options. Else planned to immigrate to South America with her fiancée. Seventeen-year-old Ernst and his mother secured passage on a ship to Shanghai, China, where they arrived in March 1939. Ernst and Hilda survived the war in Shanghai, and immigrated to the United States with Ernst’s new wife, Illo, in July 1947. Heinz and his family immigrated to England in 1939. However, Isidor and Else were unable to escape Germany. In April 1942, Isidor was deported to Kolomyja ghetto in German-occupied Poland, and likely died that year. Else was deported to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German-occupied Czechoslovakia in April 1943. In October 1944, she was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland, where she was killed.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 10 kronen note, acquired by a Jewish refugee

Object

Scrip, valued at 10 kronen, distributed in Theresienstadt (Terezin) ghetto-labor camp and acquired post-war by Ernst (Ernest) Heppner. Currency was confiscated from inmates and replaced with scrip, which could only be used in the camp. The scrip was part of an elaborate illusion to make the camp seem normal and appear as though workers were being paid for their labor, but the money had no real monetary value. Ernst was living in Breslau, Germany (now Wroclaw, Poland), with his parents, Isidor and Hilda, and his half-sister, Else, who was severely handicapped from contracting polio as a young child. He also had an older half-brother, Heinz (Henry), who lived with his wife and young child. Following the Kristallnacht program and Heinz’s subsequent arrest in November 1938, the family began looking at emigration options. Else planned to immigrate to South America with her fiancée. Seventeen-year-old Ernst and his mother secured passage on a ship to Shanghai, China, where they arrived in March 1939. Ernst and Hilda survived the war in Shanghai, and immigrated to the United States with Ernst’s new wife, Illo, in July 1947. Heinz and his family immigrated to England in 1939. However, Isidor and Else were unable to escape Germany. In April 1942, Isidor was deported to Kolomyja ghetto in German-occupied Poland, and likely died that year. Else was deported to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German-occupied Czechoslovakia in April 1943. In October 1944, she was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland, where she was killed.

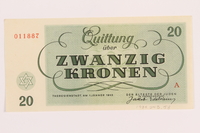

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 20 kronen note, acquired by a Jewish refugee

Object

Scrip, valued at 20 kronen, distributed in Theresienstadt (Terezin) ghetto-labor camp and acquired post-war by Ernst (Ernest) Heppner. Currency was confiscated from inmates and replaced with scrip, which could only be used in the camp. The scrip was part of an elaborate illusion to make the camp seem normal and appear as though workers were being paid for their labor, but the money had no real monetary value. Ernst was living in Breslau, Germany (now Wroclaw, Poland), with his parents, Isidor and Hilda, and his half-sister, Else, who was severely handicapped from contracting polio as a young child. He also had an older half-brother, Heinz (Henry), who lived with his wife and young child. Following the Kristallnacht program and Heinz’s subsequent arrest in November 1938, the family began looking at emigration options. Else planned to immigrate to South America with her fiancée. Seventeen-year-old Ernst and his mother secured passage on a ship to Shanghai, China, where they arrived in March 1939. Ernst and Hilda survived the war in Shanghai, and immigrated to the United States with Ernst’s new wife, Illo, in July 1947. Heinz and his family immigrated to England in 1939. However, Isidor and Else were unable to escape Germany. In April 1942, Isidor was deported to Kolomyja ghetto in German-occupied Poland, and likely died that year. Else was deported to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German-occupied Czechoslovakia in April 1943. In October 1944, she was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland, where she was killed.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 20 kronen note, acquired by a Jewish refugee

Object

Scrip, valued at 20 kronen, distributed in Theresienstadt (Terezin) ghetto-labor camp and acquired post-war by Ernst (Ernest) Heppner. Currency was confiscated from inmates and replaced with scrip, which could only be used in the camp. The scrip was part of an elaborate illusion to make the camp seem normal and appear as though workers were being paid for their labor, but the money had no real monetary value. Ernst was living in Breslau, Germany (now Wroclaw, Poland), with his parents, Isidor and Hilda, and his half-sister, Else, who was severely handicapped from contracting polio as a young child. He also had an older half-brother, Heinz (Henry), who lived with his wife and young child. Following the Kristallnacht program and Heinz’s subsequent arrest in November 1938, the family began looking at emigration options. Else planned to immigrate to South America with her fiancée. Seventeen-year-old Ernst and his mother secured passage on a ship to Shanghai, China, where they arrived in March 1939. Ernst and Hilda survived the war in Shanghai, and immigrated to the United States with Ernst’s new wife, Illo, in July 1947. Heinz and his family immigrated to England in 1939. However, Isidor and Else were unable to escape Germany. In April 1942, Isidor was deported to Kolomyja ghetto in German-occupied Poland, and likely died that year. Else was deported to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German-occupied Czechoslovakia in April 1943. In October 1944, she was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland, where she was killed.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 50 kronen note, acquired by a Jewish refugee

Object

Scrip, valued at 50 kronen, distributed in Theresienstadt (Terezin) ghetto-labor camp and acquired post-war by Ernst (Ernest) Heppner. Currency was confiscated from inmates and replaced with scrip, which could only be used in the camp. The scrip was part of an elaborate illusion to make the camp seem normal and appear as though workers were being paid for their labor, but the money had no real monetary value. Ernst was living in Breslau, Germany (now Wroclaw, Poland), with his parents, Isidor and Hilda, and his half-sister, Else, who was severely handicapped from contracting polio as a young child. He also had an older half-brother, Heinz (Henry), who lived with his wife and young child. Following the Kristallnacht program and Heinz’s subsequent arrest in November 1938, the family began looking at emigration options. Else planned to immigrate to South America with her fiancée. Seventeen-year-old Ernst and his mother secured passage on a ship to Shanghai, China, where they arrived in March 1939. Ernst and Hilda survived the war in Shanghai, and immigrated to the United States with Ernst’s new wife, Illo, in July 1947. Heinz and his family immigrated to England in 1939. However, Isidor and Else were unable to escape Germany. In April 1942, Isidor was deported to Kolomyja ghetto in German-occupied Poland, and likely died that year. Else was deported to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German-occupied Czechoslovakia in April 1943. In October 1944, she was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland, where she was killed.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 100 kronen note, acquired by a Jewish refugee

Object

Scrip, valued at 100 kronen, distributed in Theresienstadt (Terezin) ghetto-labor camp and acquired post-war by Ernst (Ernest) Heppner. Currency was confiscated from inmates and replaced with scrip, which could only be used in the camp. The scrip was part of an elaborate illusion to make the camp seem normal and appear as though workers were being paid for their labor, but the money had no real monetary value. Ernst was living in Breslau, Germany (now Wroclaw, Poland), with his parents, Isidor and Hilda, and his half-sister, Else, who was severely handicapped from contracting polio as a young child. He also had an older half-brother, Heinz (Henry), who lived with his wife and young child. Following the Kristallnacht program and Heinz’s subsequent arrest in November 1938, the family began looking at emigration options. Else planned to immigrate to South America with her fiancée. Seventeen-year-old Ernst and his mother secured passage on a ship to Shanghai, China, where they arrived in March 1939. Ernst and Hilda survived the war in Shanghai, and immigrated to the United States with Ernst’s new wife, Illo, in July 1947. Heinz and his family immigrated to England in 1939. However, Isidor and Else were unable to escape Germany. In April 1942, Isidor was deported to Kolomyja ghetto in German-occupied Poland, and likely died that year. Else was deported to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German-occupied Czechoslovakia in April 1943. In October 1944, she was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland, where she was killed.

Medal and a ribbon bar pin awarded to a Jewish refugee in Shanghai

Object

Badge awarded around 1945 by the British Boy Scouts Association to Ernst (Ernest) Heppner, a Jewish refugee in Shanghai. It was awarded by the British Red Cross for his direct (bed-to-bed) blood transfusion to a British woman, saving her life. Ernst was living in Breslau, Germany (now Wroclaw, Poland), with his parents, Isidor and Hilda, his half-sister, Else. He also had an older half-brother, Heinz (Henry), who lived with his wife and young child. Following the Kristallnacht program and Heinz’s subsequent arrest in November 1938, the family began looking at emigration options. Seventeen-year-old Ernst and his mother secured passage on a ship to Shanghai, China, where they arrived in March 1939. Ernst got a job working for a toy store branch located inside a bookstore, where he began learning to read English. He also joined a British Boy Scout troop, the Thirteenth Rovers, and the Shanghai Volunteer Corps (SVC), which reinforced the International Settlement’s municipal police. In May 1943, the Japanese occupation authorities forced the stateless refugees into a ghetto in Hongkew. In April 1945, Ernst married Illo Koratkowski, a Jewish refugee from Berlin. The following month, Germany surrendered to the Allies; Japan surrendered in August. Ernst and Illo were able to get civilian jobs with the American Army, and moved to Nanking (now, Nanjing) in 1946. The following year, Ernst, Illo, his mother, and his father-in-law immigrated to the United States. Ernst’s half-brother, Heinz and his family immigrated to England in 1939, but both his father, Isidor, and his sister, Else, were killed in the Holocaust.

Shanghai Volunteer Corps badge issued to a Jewish refugee in Shanghai

Object

Badge issued to Ernest G. Heppner, in late 1940 or early 1941, as a member of the Shanghai Volunteer Corps (SVC). Founded in 1854, the SVC was under the command of British officers and reinforced the International Settlement’s municipal police. Ernst was living in Breslau, Germany (now Wroclaw, Poland), with his parents, Isidor and Hilda, his half-sister, Else, and near his half-brother, Heinz. Following the Kristallnacht program in November 1938, and Heinz’s subsequent arrest, the family began looking at emigration options. Eighteen-year-old Ernst and his mother secured passage on a ship to Shanghai, China, where they arrived in March 1939. Ernst soon got a job working for a toy store branch located inside a bookstore, where he began to learn reading English. He also joined an established British Boy Scout troop, the Thirteenth Rovers, as well as the SVC. In May 1943, the Japanese occupation authorities forced the stateless refugees into a ghetto in Hongkew. In April 1945, Ernst married Illo Koratkowski, an immigrant from Berlin. The following month, Germany surrendered to the Allies; Japan surrendered in August. Ernst and Illo were able to get civilian jobs with the American Army, and moved to Nanking (now, Nanjing) in 1946. The following year, Ernst, Illo, his mother, and his father-in-law immigrated to the United States. The couple settled in New York City, where their daughter was born. Ernst did not learn the fates of his family until after the war. Heinz and his family immigrated to England in 1939, but both Isidor and Else were killed in the Holocaust.

Shanghai Volunteer Corps badge issued to a Jewish refugee in Shanghai

Object

Badge issued to Ernst (Ernest) Heppner, in late 1940 or 1941, as a member of the Shanghai Volunteer Corps (SVC). Founded in 1854, the SVC was under the command of British officers and reinforced the International Settlement’s municipal police. He became a driver for the transport company. Even though he had no prior driving experience, Ernst passed his test at the end of 1940. Ernst was living in Breslau, Germany (now Wroclaw, Poland), with his parents, Isidor and Hilda, his half-sister, Else, and near his half-brother, Heinz. Following the Kristallnacht program in November 1938, and Heinz’s subsequent arrest, the family began looking at emigration options. Eighteen-year-old Ernst and his mother secured passage on a ship to Shanghai, China, where they arrived in March 1939. Ernst soon got a job working for a toy store branch located inside a bookstore, where he began to learn reading English. He also joined an established British Boy Scout troop, the Thirteenth Rovers, as well as the SVC. In May 1943, the Japanese occupation authorities forced the stateless refugees into a ghetto in Hongkew. In April 1945, Ernst married Illo Koratkowski, an immigrant from Berlin. The following month, Germany surrendered to the Allies; Japan surrendered in August. Ernst and Illo were able to get civilian jobs with the American Army, and moved to Nanking (now, Nanjing) in 1946. The following year, Ernst, Illo, his mother, and his father-in-law immigrated to the United States. The couple settled in New York City, where their daughter was born. Ernst didn’t learn the fates of his family until after the war. Heinz and his family immigrated to England in 1939, but both Isidor and Else were killed in the Holocaust.

Shanghai Volunteer Corps nightstick issued to a Jewish refugee in Shanghai

Object

Wooden truncheon issued to Ernst (Ernest) Heppner, in late 1940, as a member of the Shanghai Volunteer Corps (SVC). Founded in 1854, the SVC was under the command of British officers and reinforced the International Settlement’s municipal police. He became a driver for the transport company. Even though he had no prior driving experience, Ernst passed his test at the end of 1940. Ernst was living in Breslau, Germany (now Wroclaw, Poland), with his parents, Isidor and Hilda, his half-sister, Else, and near his half-brother, Heinz. Following the Kristallnacht pogrom in November 1938, and Heinz’s subsequent arrest, the family began looking at emigration options. Eighteen-year-old Ernst and his mother secured passage on a ship to Shanghai, China, where they arrived in March 1939. Ernst soon got a job working for a toy store branch located inside a bookstore, where he began to learn reading English. He also joined an established British Boy Scout troop, the Thirteenth Rovers, as well as the SVC. In May 1943, the Japanese occupation authorities forced the stateless refugees into a ghetto in Hongkew. In April 1945, Ernst married Illo Koratkowski, an immigrant from Berlin. The following month, Germany surrendered to the Allies; Japan surrendered in August. Ernst and Illo were able to get civilian jobs with the American Army, and moved to Nanking (now, Nanjing) in 1946. The following year, Ernst, Illo, his mother, and his father-in-law immigrated to the United States. The couple settled in New York City, where their daughter was born. Ernst didn’t learn the fates of his family until after the war. Heinz and his family immigrated to England in 1939, but both Isidor and Else were killed in the Holocaust.

Ernest G. Heppner papers

Document

The Ernest G. Heppner papers consist of records documenting the Ernest Heppner and Kurt Redlich families’ departures from Nazi Europe and their lives in Japanese‐occupied Shanghai, newspapers documenting the Jewish refugee community in Shanghai, and other printed materials. Heppner family materials include biographical materials about Ernest Heppner, his mother Hilde Heppner, his wife Ilse‐Lore Heppner, her father Paul Koratkowski, and their relative Rosa Koratkowski; correspondence; and files documenting the Heppners’ and Koratkowskis’ activities in Shanghai. Biographical materials include identification papers, employment records, and travel records. Correspondents include Heppner’s father and sister who remained in Breslau and his brother’s family in England. This series also includes files documenting Ernest Heppner’s participation in the Shanghai Volunteer Corps, his and his wife’s work for the US Army Advisory Group, his mother’s social work with Jewish refugees in Shanghai, and his father‐in‐law’s participation in the Jüdische Gemeinde alongside Kurt Redlich. Redlich family materials include biographical materials about Kurt Redlich and his wife Ida, correspondence, files documenting the Jewish community and aid organizations in Shanghai, and a map and narrative describing Redlich’s experiences in Dachau after Kristallnacht. Biographical materials include identification papers, education records, and travel and immigration papers. Correspondents include family members, friends, Charles Jordan of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC), and David Kranzler, to whom Redlich provided information for Kranzler’s book, Japanese, Nazis & Jews: the Jewish refugee community of Shanghai, 1938‐1945 (a copy of which can be found in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s library). These files also include two photographs documenting the JDC in Shanghai. Shanghai newspapers include English and German language newspapers printed in Shanghai during the war and postwar years primarily for Jewish refugees from Europe. The newspapers include articles about and of interest to the Jewish community, some of which are either written by or mention Paul Koratkowski or Kurt Redlich. Printed materials include 1930s German literary magazines, materials describing the Schwarzes Fähnlein youth group to which Ernest Heppner belonged, a calendar printed by the Heppner matzo factory, newspapers clippings, and handbill notices addressed to the Jewish community in Shanghai.