- Biography

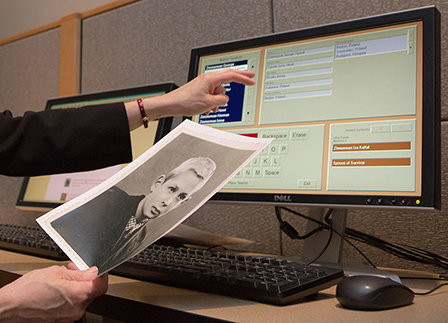

- Arnold Samuelson (1917-2002), was a U.S. Army Signal Corps photographer during World War II, who commanded a unit of photographers who took pictures of the advance of American troops through France, Belgium, Germany, and Austria, including the liberation of concentration and POW camps. The son of Swedish immigrants to the U.S., Samuelson was raised in Tacoma, Washington. He learned photography as a child, and after graduating from high school, went to work in a photo studio. Subsequently, he went to work for the Eastman Kodak Company in Portland, Oregon, where he sold camera equipment. In March 1942 Samuelson applied to flight cadet school and in May of that year was inducted into the U.S. Army. He served in the Army Air Corps before going for training as a Signal Corps photographer in January 1943. Samuelson graduated from both photographic training and officers' candidate school in July of that year, and the following month was assigned to the 167th Signal Corps company. For the next ten months he was stationed in Camp Crowder, Missouri. On July 24, 1944, the 167th Signal Corps company departed for England, where it was assigned to the 12th U.S. Army Group. Samuelson was sent to France in September. Starting in Normandy, his unit moved through Belgium and in and out of Germany. After participating in the Battle of the Bulge, Samuel was sent to the 12th Army Group headquarters in Paris. Following three weeks of desk duty he was reassigned to the 9th Armored Division. His unit was among the first U.S. troops to cross the Rhine River (at Remagen). They continued south through Germany and on May 1 crossed into Austria, where they photographed Hitler's hometown of Branau. His unit then proceeded on to Linz. On May 8, the day after V-E Day, Samuelson's unit entered the newly liberated Ebensee concentration camp and photographed its survivors. The photographers could hardly believe the state to which these men had been reduced. Samuelson expected to be transferred to the Pacific theater, but was saved from that fate by a general who owed him a favor. He then returned to Paris for a few weeks before departing for the U.S. on June 20. He served another six months at Camp Polk, Louisiana, and then was discharged. After his return to civilian life, Samuelson rarely talked about his experience as a combat photographer and seldom opened the military trunks containing his World War II photographs and memorabilia. However, 25 years into his retirement in Texas he decided to return to Europe and see if anything remained of the Ebensee camp. With the assistance of a historian at a Salzburg research institute who he discovered through the internet, Samuelson learned of the existence of the KZ Ebensee Memorial and was introduced to its director during his visit in the summer of 1996. The following winter, Time magazine featured one of Samuelson's Ebensee photos on the cover of its February 24, 1997 issue. He was pleasantly surprised that the magazine credited him as the photographer. Soon after, he received a call from Ebensee survivor, George Havas, who had recognized fellow survivors in Samuelson's photograph. Havas, a volunteer at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, had learned of the photographer's whereabouts from the director of the Ebensee Memorial. In May 1997 Samuelson returned to Austria when he was invited to be an honored guest at the dedication of the permanent exhibition at the Ebensee Memorial. For his 80th birthday on November 21, 1997, Samuelson's three daughters took him to Washington, D.C., where he met with Havas in person for the first time.

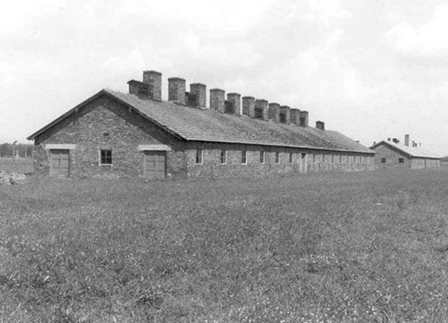

Gyorgy (now George) Havas is the son of Leo and Ruzena Havas. He was born in 1929 in Mukacevo (part of Czechoslovakia between 1919 and 1938), where his father was a physician who catered to patients from the surrounding villages. Gyorgy had one sibling, a younger brother named Robert (b. 1931). The Havas boys grew up in a home that was identifiably Jewish but not religiously observant. Gyorgy had a bar mitzvah at a local temple but attended a Czech school. He lived a rather divided existence. He had Czech friends at school and Hungarian-speaking Jewish friends at home. His parents spoke to him in Hungarian, but tried to orient him toward the dominant Czech culture. Already as a child of five or six Gyorgy understood that many people hated Jews simply for being Jewish. Through conversations at home, radio broadcasts and newsreels at the local cinema, he learned about Nazism early on, and sensed the foreboding of his community after the German annexation of Austria in March 1938. At this time, the Havas' considered emigrating to America, where Gyorgy's mother had four brothers, who had moved there in the 1920s. The brothers, in fact, arranged for visas to be sent to Mukacevo, but Leo was reluctant to leave his home and his medical practice. Gyorgy witnessed the build-up of fortifications along the Czech-Hungarian border in the summer of 1938, the Czech mobilization that took place in September, and finally the Hungarian annexation of southwest Carpathia in November of that year. Because his father was known to have been friendly toward the Czechs and sent his children to Czech schools, local Hungarian authorities took revenge on him by refusing to re-certify his medical license. He continued to practice secretly, but was under great stress, which he often took out on his family. Immediately following the Hungarian takeover, new anti-Jewish legislation was enacted that severely restricted Jewish employment, ownership of property, and access to higher education. Gyorgy's Czech school was closed, and he was transferred to a Hungarian gymnasium. Two years later, when Jews were prohibited from attending the state-run gymnasium, Gyorgy was compelled to move to the Hebrew gymnasium, for which he had to learn modern Hebrew from scratch. For a time Gyorgy and his classmates were compelled to join the Hungarian paramilitary youth movement, which involved weekly patriotic lectures and calisthenics. When this "privilege" was withdrawn for Jews, the students of the Hebrew gymnasium were made to serve once a week in labor units for which they donned yellow armbands and performed menial tasks at a local agricultural school. In 1941 Gyorgy's father was drafted into the Hungarian labor service. Fortunately, he had a sympathetic commander who did not make him work, and he was soon discharged. With the help of a colleague, Leo was able to continue practicing medicine to a limited extent. In January of 1944 he had a heart attack. He was still recuperating when the Germans occupied Hungary in March. On April 19 the Jews of Mukacevo were rounded up. While most were taken to the newly designated ghetto, others, including the Havas family, were marched to a local brick factory, which had been established as an assembly camp for Jews from the neighboring villages. Leo was desperate to get his family out of the factory and into the ghetto, and to this end tried to ingratiate himself with an SS officer. On May 11 he saw a chance for them to get out and quickly got his wife and boys to jump onto a truck that was headed to the ghetto. Leo remained behind. However, on May 15 they were picked up in the ghetto and driven, along with Leo, to a second brick factory on the outskirts of town. There they were beaten by a Hungarian policeman and an SS man and then were loaded onto an empty freight train at an adjacent railroad siding. Several hours later a large group of Jews was boarded onto the boxcars and the deportation train departed for Auschwitz. When the train reached Slovakia, the Hungarian guards were replaced by German SS. Immediately upon their arrival in Auschwitz on May 17, Leo and the boys were separated from Ruzena, but they all passed the selection process and were sent to the prison camp. A few days later when the men were divided between those over the age of 18 and those below, Gyorgy and Robert were separated from their father, who they never saw again. On May 26 the boys were included in a transport going to Mauthausen. Despite Gyorgy's efforts to stay with his brother, they were forcibly separated during their initial processing in the camp. Gyorgy remained in Mauthausen only five days before being transferred to the sub-camp of Ebensee. Robert, too, remained only a short time before being sent to the Gusen sub-camp, where he died on December 2, 1944. Gyorgy was among the first Jews sent to Ebensee, which was a camp still under construction when he arrived on June 2, 1944. During the 11 months he spent in Ebensee Gyorgy worked in many jobs, including tunnel construction, erecting prefabricated barracks, and excavating pits for the storage of potatoes for the winter. On February 28 Gyorgy had an accident at his work site and broke his wrist. He was then sent to the separate Jewish hospital barracks, where he got virtually nothing to eat. He was still in the hospital when the Americans liberated the camp on May 6, 1945. On May 8 an American photographer ventured into the hospital barracks and started taking pictures of the emaciated prisoners. That same day Gyorgy was moved to the Czech barracks in the camp, where his health continued to deteriorate because his body couldn't digest the bread and soup he was getting. On June 6, he left the camp with a repatriation transport to Czechoslovakia. As he was in a very weak condition, he was urged to get off in Prague and seek help from the Red Cross. This he did and was finally admitted to a real hospital, where he remained for several months. During his convalescence he was reunited with his mother. Ruzena had been sent from Auschwitz to Germany, where she was put to work first in the Gelsenkirchen labor camp and later, in Essen. In the early spring of 1945 she was evacuated to Bergen-Belsen, where she was liberated on April 15. Several weeks later she too joined a repatriation transport to Czechoslovakia. When she arrived in Prague she met someone from Mukacevo who informed her that Gyorgy was in town and took her to the hospital. With the assistance of Ruzena's brothers, she and Gyorgy received new American visas in November 1945. It was another two years, however, before they left Prague by plane for the U.S. Two years after the liberation Gyorgy learned that his father had been a member of the Sonderkommando in Auschwitz and that he had died in the Sonderkommando uprising of October 7, 1944, that resulted in the destruction of one of the gas chambers.

[Source: Havas, George. "Interview with George Havas," August 26, 1996, U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum Oral History Project.]