- So we'll start to record.

- We're going to start all over now.

- I'm going to say, good morning, this is Barbara Kreines,

- and it's Wednesday, April 28, 1981.

- And I have the pleasure of speaking

- to Mr. Albert Geisel in his beautiful apartment in Roselawn

- on Section Road.

- And it is a beautiful apartment.

- Mr. Geisel, would you begin this morning

- by telling us a little bit about your birthplace,

- when you were born, and about your general family

- background in Germany?

- I am Albert Geisel.

- I was born May 18, 1907 in Rheinbach near Bonn

- as a son of Hermann and Sophie Geisel.

- I had two older sisters and one younger brother.

- When I was six years old, I attended a Catholic partial

- school to my 13th year when I graduated.

- After that I attended for three years what would

- you call a trade school.

- And I entered the business of my father.

- He was-- we had a meat market and were cattle dealers.

- In 1913, when, I was attending school,

- we had a big occasion in our town.

- The kaiser, or rather, the emperor, was passing our town,

- and all schoolchildren were lining up the streets.

- Then in 1914, when World War number one started,

- I still remember very well as soldiers from all

- over were quartered in private houses.

- They came with horses and everything.

- Everything went to the west into France--

- first into Belgium.

- My mother, who had four brothers, who

- were living near the Belgian border,

- about 30, 32 miles where we were living,

- who had all also a meat market, they had to close--

- they had to close their businesses when they all

- were inducted in the army.

- My youngest uncle, Uncle Karl, he already

- was wounded in Belgium.

- But he was lucky.

- He was transferred back into Germany

- and stayed all during the war in Berlin.

- They all advanced to corporal, sergeant, and second lieutenant.

- The second lieutenant, my Uncle Alex, and when the Germans--

- Germany was defeated in the war, he rode back on his horse

- and was lucky.

- And a shell did strike his cap, but he was not wounded.

- But might I go back?

- In December 1916, my father was inducted in the army also.

- He was one of the oldest soldiers.

- He was born in October '69.

- If he had born in August '69, he had not been inducted anymore.

- He had his basic training in Koblenz am Rhein.

- And on one day, he had a few days' leave,

- but then through an informers for bad weather,

- he was ordered back to his unit, and was all by himself

- back out to France without any notice.

- And he had really a rough time.

- But at that time, as I say before, we were four children.

- My mother was all by herself with the four children.

- I never will forget.

- I was 10 years old when I slaughtered the first calf.

- My older sister was four years older than I am.

- She helped my mother cutting up meat.

- But the hardship was really great.

- My mother, who weighed 180 pounds,

- she went down to 125 pounds.

- But then at the end--

- no, I guess it was at the beginning of April 18, 1918,

- my father got his discharge due to his age.

- Going a little back about our family history,

- we were for generation and generation in the same locality.

- My mother-- or better, my mother's mother, my grandmother,

- she came from Godesburg, also near Bonn.

- My father's mother, she came from Unkel am Rhein,

- a city near Remagen.

- So coming back to my private life, as I grew older

- grew older our community consisted of about 99%

- of people of the Catholic faith.

- And I had only Catholic friends, hardly, any connections

- with Jews.

- And socially, Sundays, we went to walks in the park

- or went for playing cards in the house or maybe

- in a saloon for an hour or two.

- And after that, we attended our business.

- The farmers had to attend the cattle.

- We had maybe cattle.

- I attend cattle.

- And during the week, we had our house there.

- We had our business.

- We had land.

- We had farm.

- We had-- we were very well-to-do people.

- And yet you knew you were Jewish.

- And how did you express that Jewishness?

- Was there any Jewish community at all?

- Oh, yes.

- We had about-- we had our synagogues there.

- We had about 12 Jewish families in our community.

- And in the surrounding villages, there were maybe--

- I mean, the next villages were maybe three miles apart,

- and they had maybe three or four Jewish families.

- And very many, they attended the service in Rheinbach,

- in our community.

- It was Orthodox, I guess?

- What kind of a-- do you remember?

- And who conducted it?

- There wasn't a rabbi there?

- There was no rabbi, but yes, you could say Orthodox

- because at that time we were eating kosher meat.

- My dad was a chauffeur.

- And so there were other people.

- But as soon the Nazis came and they took the knives away,

- naturally we ate all meat which was cattle,

- from cattle which were not killed kosher, maybe

- under the circumstances.

- How was the-- how large was the community itself?

- About 5,000 population.

- But in our community, as I said before, we had a meat market,

- and there were about 10 meat markets.

- But at the beginning, the Jews, they

- were selling only beef or lamb, no pork.

- But later when I grew older, we had everything.

- We slaughtered pigs and everything.

- But my dad was so conscientious what quality meat

- he was handling.

- He had only the best, and I guess

- there was nobody in town who didn't

- buy the meat in our place.

- Also, there were 10 competitors.

- And we had--

- So socially or a business-like, we didn't any--

- it didn't feel any different.

- But there were certain people, also

- they were dealing with us business, but business concern.

- But socially, they looked a little down on us.

- For instance, when we became an age where we learned dancing,

- the teacher came.

- And on one side there were the girls and on one side the men.

- For instance, when my sisters were in that position,

- there were certain big farmers sons

- who hesitated to dance with.

- But those occasions, they were in the minority.

- I mean, it doesn't appear very often.

- The boys would get bar mitzvah?

- Oh, yes.

- Oh, yes.

- My bar mitzvah was as big as a wedding.

- I mean, big attendance and everything.

- Oh, yes.

- And--

- It sounds like there was a lot of tolerance

- and was very tolerant of one another's beliefs.

- So in other words, when my dad came back from the army,

- we had inflation.

- We got really poor.

- We had all to start from the beginning.

- But I was pretty much pushing on.

- I was more or less running the show,

- and everything was developing to our satisfaction.

- Then when the war--

- when Hitler came to power, as I mentioned before,

- socially we had nothing to worry.

- And we were financially so well off

- that we didn't worry because we thought,

- how many people are worse off than we are and we never

- had done anything wrong as far as having a parking ticket,

- any violations.

- And also there were propaganda that people

- shouldn't deal with Jews, but still the farmers dealt with us.

- Belonged to the party or not to the party,

- they were dealing with us.

- Also they were threatened.

- The fact wouldn't even the bishop [GERMAN] I mean,

- the Catholic higher priest, they were denounced openly

- that they were dealing still with the Jews.

- Because he was proud that he was,

- mentioned that he was dealing with us.

- But nevertheless, that went on and on and on.

- Finally, everything was rationed,

- and a Nazi was put in charge to the market in Bonn.

- From there, later on were the cattle that distribute.

- And the classification came, a, b, c, d,

- that means quality-wise.

- And naturally, the Jews couldn't get the best quality.

- They gave them cattle which couldn't even walk anymore.

- But nevertheless, I had good friends

- to whom I gave that kind of meat what I used to produce sausage.

- And they had more the best quality

- meat which they had no use for.

- So they were astonished as I still could keep up my trade

- and had the best meat to sell.

- Because I got it from the competition who

- had no use for it, and I didn't have

- to sell the poor quality meat because I had an outlet for it.

- Then came with hogs.

- They didn't get any.

- My sister, who was not Jewish-looking whatsoever,

- she went in the office of that so-called Nazi,

- and he said, sure, you get a hog.

- Yeah.

- Somebody mentioned Jew.

- No, you are not Jewish.

- So for one week that helped.

- She got a hog.

- But the next time, it was out.

- So making the story short, in 1938,

- I was ordered to the big office in Bonn when I was asked,

- I should give up my trade.

- But in the meantime, there was not much trade anymore.

- I mean, just that you had the permission.

- And I said to that man, I did nothing wrong,

- and I am not going to give it up.

- So the man said-- was a very nice man.

- He said, now, listen.

- You know they don't want that you have it.

- If we let you have your trade, you

- give it up the first of the year voluntarily.

- I said that is a deal.

- Because I mean, I only want to show

- I had not done nothing wrong.

- But in the meantime, my brother had emigrated to New York,

- to America.

- And we were told that a very distant relative--

- Was your brother in the business with you?

- A very distant relative who was in America also

- with his sister when his parents were living in Dusseldorf.

- They were leaving Germany, and at that time

- I was asked to visit them in order

- to give them some messages to my brother

- or to hear something, news about my brother

- and the life in America.

- And I had a fairly new car.

- On Wednesday, I had the car outside

- and didn't want to use it anymore.

- I want to leave it clean to travel to Dusseldorf, which was

- about 90 miles from Rheinbach.

- And on a Thursday morning, I take my bike

- and go to two neighboring villages.

- The first one was Miel and then Ludendorf.

- And that was a little after noon time.

- I left that village and drove with one hand on my bike.

- With the other hand, I was eating a sandwich.

- And then came opposite towards me

- on a bike one of a bigger richer farmer, wealthy farmers

- from that village.

- And he goes off the bike and he asked, Geisel,

- where are you going?

- I ask why?

- Yeah, I just come from Rheinbach.

- They arrested all Jews there, including your dad

- and your fat mayor, an SA, was watching how

- they tear the synagogue down.

- Now, one can imagine I couldn't eat my sandwich anymore.

- I turned around and went back in that village

- and went to a customer.

- And I said Mrs. [? Schacher, ?] that Peter Fuchs ] just comes

- and tells me that and that.

- So she said to one of her sons-- those people had two sons--

- Henry, you get your bike and you go to Rheinbach

- and find out what is what.

- And I was sitting there and wait.

- How long was the distance?

- About four miles.

- And after two hours, that fellow comes back and says,

- not looking in my face anymore, I couldn't reach your people.

- I went to your neighbor, who was a farmer, and through the wall

- I talked to your sister and said--

- and they told me that your dad is arrested,

- and if you don't come home, they will arrest your mother

- and your sister also.

- So that fellow's mother said, Albert, what can you do?

- You have to go home, and go from that village Ludendorf

- in order to get to Rheinbach, I had

- to pass Oberdrees, another village.

- And there were two farmers, women, making the expression,

- oh, there is still one coming.

- So in the end of that village, a custom of ours,

- we had a saloon there.

- I go in there, and I said, Frau [? Merber, ?] I use your phone.

- I didn't ask for an answer.

- I go and called my sister.

- And she said, Albert, you better be here by then and then.

- Otherwise, they will get me and mother too.

- In the outskirts of Rheinbach, there

- was the newest and biggest penitentiary of Prussia

- with all the houses where the guards were living.

- Was almost a village by itself.

- But in the outskirts there, my sister, another distant cousin

- came already, expecting me and informed me what is going on.

- And in order to go out to our house,

- we had to pass the main street.

- I was wearing long brown boots like the SA--

- SA was wearing.

- And I came home.

- My mother had cooked some pea soup she wants to give me,

- but I wasn't able to eat pea soup.

- So my sister accompanied me, and we went to the courthouse.

- And as I said, a small community, everything, everybody

- knows each other.

- And the caretaker of the courthouse, a real smart party

- man, addressed me only Mr. Geisel, Mr. Geisel.

- I had taken a prayer book along.

- And he said to the fellow, take some sheets for Mr. Geisel

- and take some books to read for Mr. Geisel.

- And I was put in a cell by myself.

- And after a few hours, I hear slamming of doors.

- And finally, my cell door was opened.

- And party people from Bonn came and asked, what is your name?

- What was your occupation?

- My occupation is cattle dealer because I still

- had the permission.

- So they left me.

- Was on a Thursday.

- But may I interrupt you?

- All this happened-- by coincidence,

- I had not listened to the radio, and I

- didn't know what had happened in Paris when that so-called Rath

- was murdered.

- And that was the reason they took all those actions

- against the Jews.

- But that evening, my dad was released because nobody should

- be arrested over 60 years old.

- My dad was past 60 years old.

- They let him go.

- The next Friday before lunch, we were called out.

- There was a big commotion at the courthouse,

- and everybody was assembled.

- My sister's there with a packed suitcase for me and a truck

- waiting for us.

- And we all loaded on that truck and driven through the city,

- then out of the city.

- We didn't know what our destination was,

- but then we were brought to the penitentiary in Brauweiler.

- That was near Cologne.

- That was on a Friday.

- Then I was put together in a cell.

- There were already three more people,

- one from Bonn, one young fellow from Brühl--

- That's all close by--

- 16 years old.

- And so every day for a short time we were let out.

- And if I remember well, on a Monday morning,

- it was about 1:30 in the morning, we were called out.

- The first time that I saw floodlights,

- I mean it was in the middle of the night was daylight.

- And we were lined up and escorted

- from the police in Cologne.

- Cologne was the biggest city in the Rhineland.

- And they called the police a Schupo.

- They were escorting us on both sides,

- and we were marched to the railroad station in Brauweiler.

- And at that time, in Germany, the railroad

- had first, second, third, and fourth class.

- First and second class were nice upholstered cars.

- The third class was cars with small compartments

- with two wooden benches, which hold maybe eight people.

- And the fourth class were huge cars

- which had wooden benches in the middle and aisle.

- And with us was a distant cousin of ours.

- He had been a prisoner of war in the First World War

- when he said, keep your nose back, keep your nose back.

- So those people on that railroad station,

- they were forced in those cars that they couldn't move anymore.

- And finally as that cousin said, keep your nose back,

- there were only 14 people left.

- So we came in that car.

- We had plenty of room to sit and to stretch

- and were accompanied with those Schupos.

- I wanted to have conversation with them because I

- knew some people in the Schupo.

- And they said, yeah, we are not supposed to talk to you.

- So we left then that Brauweiler, the next big station

- what we passed.

- Can I interrupt you?

- Who was-- I'm a little confused.

- Just you went?

- Not the rest of your family?

- Just for my family?

- Yeah, only one. yes, yes, yes, yes.

- There was only my parents and my sister with her two boys

- left and myself.

- But the rest of the men from our community.

- And when we pass--

- when we passed Cologne, our train

- consisted of about 600 people.

- From Cologne, we went up along the river Rhine to Koblenz.

- There were some more cars connected then.

- We were not 600 people--

- 1,200 people.

- And all big railway station which

- we were passing, through the loudspeaker

- came, special train number so and so and so and so.

- And I myself had no idea where we were going.

- And I don't recall anymore if we traveled for a couple of days,

- but those Schupos, there were very decent.

- And those big railroad stations where

- we had to stop, with our money they went to the commission

- stands and got some chocolate or a cup of coffee or something.

- So finally it was at night.

- We came to a railroad station.

- And our Schupo escorts left with the words "you will think of us

- very often."

- In the same moment from one side of the train,

- SS came with machine guns, came in

- on one side on the left on the other side with a warning,

- nobody goes on a door, nobody goes on a window.

- You will be shot.

- So we're sitting quietly.

- And then we heard slamming of doors.

- And finally, our door were opened.

- And when we got out after being for a few days or nights

- in there, and it was November, cold,

- misty winter night, we were sweating and shivering

- when we came in that cold.

- We were lined up.

- On another platform was a whole train with cattle cars.

- And then we were marched with that cattle car, myself with one

- hand my suitcase.

- Then that cattle car was opened.

- Get in that car.

- And at that time, I was pretty much alert.

- I didn't use the steps on that car.

- There were two steps on that car.

- With one hand, a handle on that car, with the other step

- I was in that car.

- But the one who wasn't as fast right with the machine gun

- butt over them.

- Now, as I said, we were only 14 to 16 people.

- The door was closed after that.

- But after a few minutes, that door was open.

- Some more people came in.

- Again, beating with us because those people

- were not quite as alert and as fast.

- And--

- So that was repeated and repeated.

- But nobody could move anymore.

- Then the door still was opened up.

- And the people were-- it was impossible, impossible.

- Nevertheless, like you load sheep in a car,

- crush them in there.

- Then the people couldn't breathe.

- I was lucky.

- I was fairly tall and could breathe over

- the head of the other people.

- And then people in the corner of those cars were air shafts.

- They wanted to open them up.

- Then they shout, we shoot if you don't stay away from that.

- All right.

- After a short time, we heard a whistle and the locomotive

- pulled on.

- But only a few yards in order to stop and go

- backwards only to shake us up.

- So I don't know how long, 15 minutes, 20 minutes that

- went on.

- And then we stood.

- But I must say, that railroad station

- was Munich where we were.

- And then after that short trip, get out, very careful,

- very careful.

- Because in the meantime, from that mist that

- was kind of ice slippery, then we

- were lined up again to four people.

- And then we were in Dachau.

- Then the commands.

- One, two, three, forward, march.

- Double time, stop, double time.

- And I was real-- like a machine.

- But those people who were maybe physically

- were not alert as much, with those machine gun

- butts, bing, bing, bing.

- So that was only a small distance.

- I don't know how many thousand people were assembled,

- and then some SS big shots from SS was standing there

- in their long woolen coat and big boots and held a speech.

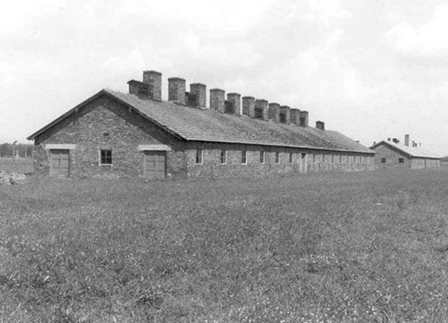

- Then we were marched between barracks.

- We have to throw our suitcases away.

- Then those barracks, there was--

- when you entered those barracks, to the left and right

- was a room.

- And as I said, that distant cousin of ours again,

- keep your nose back, keep your nose back.

- Those ones who went in first, there

- was a rafter when you go in there,

- but the lid was taken off so there was a hole.

- and people who were not alert and they tripped over that hole.

- But on left and right were standing

- one of those first inmates of the prison

- camp, those former communists.

- They were standing in there and beating the people from the left

- to the right when they were entering those Rooms then

- came shout again from inside, impossible with this filth.

- We can't breathe anymore.

- And there again we were only less than 20 people left.

- We were left then in that other empty room all by ourselves.

- And we were then lined up, and then came an SS

- and started on first, what was your occupation?

- I was a banker in Cologne.

- Where you got those ribbons from?

- There were rewards what I got in World War number one

- to save 650 people's lives to live--

- when we were stationed in Italy.

- When I was-- listen, a mine was being laid or something.

- So then that man was then really impressed.

- So that particular man said, may I ask for some water for myself

- and for my comrades here?

- You get water.

- Then in a few minutes, they came with a bucket

- with water what was handed from one to the other.

- And I can assure you, champagne can't taste as good

- as that water tasted.

- Then the floor was covered with straw.

- We had to lay down.

- We couldn't stand up.

- We had to lay down.

- Then they came around and throw everybody

- a piece of dry rye bread.

- But I hadn't eaten for a couple of days.

- Nobody was able to swallow that bread because it didn't go down

- the throat.

- And I myself, I kept myself a little fresh

- as my sister had given me in my suitcase quite a bit

- a peppermint along.

- And so for myself and the others I distributed peppermint.

- So after that first night, we had to fall out again

- and picked up our suitcases.

- And then we were processed.

- But that went so slow, so slow.

- In the meantime, one SS came after the other.

- What was your occupation and this and this and that?

- But finally, it became my turn.

- On a table was sitting an SS and a former communist,

- a political prisoner as his assistant.

- I had to empty my suitcase.

- I had there quite a number of stockings, which my mother had

- knitted, and three, four, five shirts, and had a prayer book.

- And as soon he saw that, he threw that away.

- And then he had a piece of paper.

- He said, what is that kind of Jewish writing?

- I said, that is a diploma what my great-grandfather

- got when he served in the army from 1894 to 1897 in [GERMAN].

- Then he said to that helper, put it together with values.

- Then I had 40 marks in money along.

- And due to that, I was the only one who could keep the money.

- Everybody had every penny taken away.

- From there, we got all--

- the barber had our hair taken off.

- They were out of prison garb, so we could

- keep our clothes, our suits.

- But I had to give up my boots.

- I got shoes issued.

- From there we went in a bathroom with all kinds of showers,

- all in tile, wonderful.

- And coming under that shower, that gave you new life.

- Wonderful.

- And lucky as I was again, as soon

- as [INAUDIBLE] was through, then we

- had to go, nude as we were, to a row of doctors

- to become examined.

- But as soon I was through, SS came.

- And they took that movable shower head,

- and the people were asked, come over here.

- Open your mouth.

- Say ah.

- And they put that water in their mouth,

- and the people got to the floor.

- The fact, I know quite a few one,

- horse dealer from Euskirchen, nearby city, and that

- did him bum on the floor.

- I know one cattle dealer, he had a crippled leg.

- He had to wear on his shoes high heels.

- Him, men more than six feet tall, open your mouth, eh!

- Until they fell to the floor.

- All right.

- From there, we came then to our assigned barracks.

- I was in block 26 room one.

- And the funniest part what was, there

- was one fellow, Walter [? Berns ?] from Cologne.

- We left Germany over from Holland to England

- where I had to stay, oh, for a year

- before I am able to come to America.

- And that's the same Walter [? Berns. ?]

- He was assigned to the same barracks where I was.

- His father, he was in block 28, the next block.

- And the other people from my hometown, they weren't block 28.

- But then it happened, they had a PX.

- Every day, we could make a list where

- somebody was sent to buy food for us,

- like bread or dairy butter, what you were not even able to buy

- on the outside anymore.

- And we were so surprised.

- And so everybody, maybe some acquaintance of mine,

- for 14, 16 people were gathering around me,

- and I helped them through.

- Everybody-- I felt sorry for the others

- had to look on because you could take care of dozens

- but not of hundreds.

- But after a few days, that was interrupted, that we

- couldn't buy-- only could buy certain things.

- But then after being there, you could write home for money,

- and they could send you, if I recall

- right, every two weeks $15.

- But anyhow, being in that barracks, after two days,

- we were called to give our clothes up.

- In the meantime, they had enough prison clothes again.

- It was the blue and white stripes, just thin linen.

- But at that time when I went there,

- and I had only a few pennies with me,

- I said to that political prisoner,

- let me get out my suitcase.

- And I gave him those few pennies and--

- but find your suitcase and hundreds of suitcases.

- And he was anxious himself, but I made it.

- When I took three or four pairs of socks out or my shirts out,

- when I came back to the barracks,

- and that wearing one shirt, I wore five shirts.

- I was out already before they were able to.

- And then from other times, we had to go.

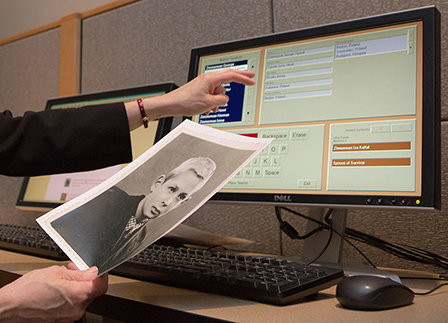

- You had your picture taken.

- You had to sit in a chair.

- And as soon that picture was taken, if you were not alert

- and were out of that chair, they pushed a button and a needle

- came out where you were sitting.

- But as I said we were marching.

- And I was fairly tall, and I was pretty much in front.

- And our political prisoners were our direct guards.

- And I heard a voice, don't fall asleep in front.

- But I never was expecting that he was referring to me.

- All of a sudden, I was hit on my behind

- that I couldn't stand the pain.

- And I can assure you, for more than a half

- a year when I was laying in bed and was shifting from one side,

- I had to go on my hands not that I was able

- but that was only a minor infliction.

- The fact, some other time we were marching.

- We would halt. And one other SS comes.

- We looked at each other, like a sudden,

- he tells me, what, did you try to hit me?

- Just provocation.

- And then with his gloved hand, he hit me in the face.

- But it was more aggravating than harmful.

- That was, thanks God, the only experience what I had.

- So I was-- in the meantime, that was a daily routine.

- As I said, we had to go in the morning or in the evening.

- One poor fellow, he was carrying from his other people

- only sheet thrown him.

- Only a skeleton, and one day he was dead anyhow.

- I mean, it was nothing left of him.

- But one episode, as I was a block 26 room one,

- and in room two, one of political prisoners,

- they must have beaten him half crazy,

- was now the boss in that room two.

- And one day he comes in our ROOM and there

- was a young fellow, an athlete, more than six feet tall.

- And he made a remark, all the equipment

- here is only crap anyhow.

- He was referring to the stonework.

- What did you say?

- That's all crap what you got here.

- And that political prisoner, small guy,

- he could hardly reach him, hit that guy left and right

- in the face.

- What did you say about it this?

- It's all crap what you got here.

- Very proud young fellow.

- And he said, what did you say?

- And he kept on hitting him and hitting him only

- in the face and mouth.

- And finally the blood comes out in his mouth and his nose.

- And we were begging that guy say every nice number one.

- And finally he said, everything.

- So then he let him go.

- So another time, we were all assembled out there.

- Those big SS there, they called names.

- And there come some poor old Jewish people

- in their prison dress.

- And what is your name?

- So on.

- Now, in order to make it short, they

- call out maybe a dozen people.

- Look at them.

- In other words, what creatures.

- They represent seven million marks.

- You know, former big shots in big business and so on.

- Then there always were informers.

- As I said, I was lucky and wore my warm underwear.

- And other people, there were people from Austria,

- from South Germany.

- They were arrested at their job, off the street.

- Some, they were doing road work, construction work.

- They had nothing.

- Just when somebody must have told them,

- they had under their prison clothes

- that linen clothes themselves, blocked up with newspapers.

- Paper holds warmth.

- And somebody had informed about that.

- So when we were all appealed on a big place,

- you had to put it all there.

- And afterwards, they had to also clean it up.

- So those people were later on freezing to death.

- Well, in the meantime comes Christmas.

- Or I may interrupt myself again.

- We was were so hungry, you pick up

- your Food there was in a corner like you put potatoes

- for the pigs.

- We could pick up a potato or two but you were eating them

- with the peeling as they were.

- There were herrings.

- They were not cleaned.

- You ate them head and tail and everything.

- Even if you were thirsty like the dickens afterwards.

- So in the meantime, Christmas came along

- and the first time we had a good meal.

- We had soup meat and soup that tastes like a home-cooked meal.

- We felt wonderful.

- The following day, we had just the leftover

- but still it tasted good.

- Then the 28th of December, my name was called.

- And all those people whose names were called

- were processed and could be discharged.

- But where we were standing there,

- you had to go before the doctors again.

- And those who were physically not fit.

- The fact, there was one fellow, Alfred [? Berney ?] from Norway

- he was all the time he couldn't wear shoes.

- He was walking on boards.

- He had his hands always in sleeves.

- They were full of pus, all infected.

- And his name was called, but he didn't get his discharge

- because the outside world shouldn't

- see in what conditions we were.

- So I guess it was in the afternoon

- before we were processed.

- We came in a train, a warm train, a short ride.

- 10 minutes, 15 minutes, we came to the railroad

- station in Munich where a Jewish committee took over.

- And then we got our tickets on the train.

- And naturally, before I left, I gave all my shirts

- to the people who were left.

- And I looked funny because I had a shirt.

- No collar and tie with my bare head.

- But we're able to travel with other civilians in the train.

- So the second day in the morning at 8:30, I arrived in Bonn.

- We had to change trains.

- But from the railroad station, I called home

- that I would come with a train so and so.

- And I came then home.

- That was about the 28th, 29th of December 30, 1918--

- 1938.

- But going back, as I said, I had two sisters.

- They were married in Mosbach, Baden.

- And they had applied for quota to emigrate to United States.

- And one of my visits in Mosbach.

- They had to do something in the American consulate in Stuttgart.

- And they asked me to come along, I should register too.

- And I was laughing, at that time it was not

- right to emigrate because there was--

- I liked it too much where I was.

- And so I got the quota number 10,000 and something.

- And actually when I came back from that visit home,

- my sister at home said, yeah, you think only of yourself.

- Why didn't you take a quota number for us too?

- But then they made arrangements from home.

- And in the meantime, they got already the quota number 25,000

- and something.

- What's a quota number?

- Well, that many people can emigrate.

- You see at that time only 2,000 to 3,000 people a year were

- allowed to emigrate.

- And at that time, while I was in Dachau, and the reason

- that I got my discharge first, those getting the discharge who

- had been veterans of World War number one,

- and they asked us first, while I was in concentration lager,

- they had to give up our car.

- But then they want to sell all our possessions, house and land.

- And my sister claimed we can do nothing.

- My brother took care of all financial things.

- We can do nothing without him.

- And she went several times to the Gestapo

- in Bonn-- in Cologne.

- And as I said, she was--

- as she didn't look Jewish, she was always fairly well accepted.

- And finally, due to that, I got my discharge.

- But then I got on a [GERMAN] visa.

- That means I had no permit to work,

- that I could emigrate to England in order

- to wait for my quota number.

- So in March '39, I left Germany, went to England,

- hardly speaking the language.

- And from Harwich, the port city of England,

- we left from Hook of Holland, the port city in Holland.

- When they arrived in Harwich, England, the port city,

- and there was with a train to London.

- There was somebody from the Jewish committee--

- that was at that time the Bloomsbury House--

- who led us to the Bloomsbury House.

- And it happened at the Bloomsbury House,

- the lady in charge, very, very essential lady, Mrs. Schwab,

- and a fellow from the nearby village from us

- was the chauffeur of that lady.

- And while waiting, waiting, waiting

- to be processed from that committee, what happened to me,

- I was told, why don't you go and make

- your financial arrangements?

- Because I had money sent over from the United States

- to the Chase Manhattan Bank branch of London.

- When I came there, huge room, people all like aristocrats,

- and me not speaking English.

- And they said, yeah, what kind of reference you got?

- I said, reference?

- I got a brother there, and I got my dad's cousin there.

- I don't know anybody in America.

- I mean, as good as I acquit myself.

- Yeah, the reason that we asked for reference,

- we don't want any people who have connections

- with Al Capone as customers.

- But OK, we take your money.

- So they gave me a checkbook.

- In the meantime, I come back to that Bloomsbury House,

- and that fellow whom we know, he said,

- you take the subway, to Belsize Park Gardens.

- There is a rooming house where my parents lived too

- when they came here.

- But my English was so good.

- I went to that station.

- I said, I want a ticket for Belsize Park.

- [LAUGHS] Because I didn't know.

- But anyhow, I made it there.

- And so every--

- I was then able to attend every day a class to learn English.

- But my main reason was to find ways to get my parents

- and sister with her two boys out and thinking

- that the acquaintance of ours with the chauffeur of Mrs.

- Schwab, had a step ahead when he told me, oh, it's just a word.

- That's nothing.

- But there was no progress and no progress.

- I am not ashamed to say I was laying

- in bed, crying how helpless I was, and not able to work.

- I became just more desperate and desperate.

- And that man himself, I mean, most likely

- he talked bigger than he was.

- But after a few months, he asked me

- to come in and see Mrs. Schwab.

- I go in that Mrs. Schwab, and I told her the situation.

- She said, how much money you got?

- I said, yeah, my parents so and so.

- Yeah, can you spare 100 pounds or what it was?

- Or $100?

- For your nephews?

- And said fine.

- I was with that lady not two minutes.

- I was referred to room so-and-so.

- And when I came, I come from Mrs. Schwab.

- Every was on the right feet.

- And in less than five minutes, there was the permission

- that my parents could come, my sister

- comes on a domestic permit to take care of my parents.

- And the children come on a children's permit.

- So right away, the permit was there.

- I wonder why it worked so quickly.

- Then they were talking, there will be the war.

- And if I recall right, the war was already

- declared on a Saturday.

- I got a call from home.

- My sister is at the telephone, and she said,

- we are leaving today.

- We are tomorrow morning in London on Victoria station.

- And as I said, I was at that rooming house.

- And everybody looked so pity for me.

- There was already war, and they said we're coming.

- The next morning, I go to the Victoria station,

- and the train comes.

- I mean I had, in the meantime that I had left in March,

- and that was in August.

- And then I see my parents on the [? boats. ?] And I took a taxi

- and went to the boarding house.

- And then everybody said, yeah, Geisel, I will tell you,

- we never believed that your parents still gotten out,

- and they were still lucky on the border.

- That was the last train for Germany--

- was leaving Germany.

- And they kept my father back, and the others

- were already in the train and the whistle blow already.

- And then finally they let my father go too.

- And so they arrived and then we went to the boarding house.

- And we stayed in there a short while.

- And the English people, they had vacated their houses

- and went to the country.

- So there were apartments advertised, houses advertised.

- And I rented a house on Selborne Gardens.

- And the fact, Then in May 4--

- march '40 I got--

- my quota was called.

- I went to the American consulate and got my visa.

- Then most of the people from my boarding house

- were living at the same place.

- In my early talk, that Alfred [? Berns, ?]

- whom I never had seen any more in England,

- came on the same train on the same boat,

- went with me together again to America.

- Then I left my parents and sister in England.

- And I left.

- And when we came, our ship should go from Liverpool,

- but we were delayed due to the German u-boats

- and stayed overnight in a hotel.

- Then we left with the SS Georgic, which

- was later torpedoed and sunk.

- But he was one of the biggest boats what the Cunard Line had.

- And I must say, the first evening,

- that meal was so wonderful, tasted so good and everybody--

- The next morning, I got up, had wonderful breakfast.

- But I was wondering.

- The dining room was almost empty and the day before was crowded.

- So I went up to the upper deck.

- And there was a man who had been always so friendly,

- but he was standing on the railing of the boat

- relieving himself.

- But I was laughing.

- That sea was so stormy.

- I went then on the upper deck, on a small stairs up.

- But everything was shaking, so I didn't stay.

- Only stand up up there only for a few minutes.

- And I went down there, but I was hardly down.

- I was in a bad--

- bad shape myself.

- I made it to the bathroom, which was crowded.

- Then I must say, I got so sick.

- I guess it took nine days to come over.

- I didn't leave my berth until the day

- before we hit the United States.

- And so I arrived in the United States.

- My sister in New York waited for me.

- My brother, who was in Chicago, but I

- intended to stay a week in New York.

- I met some acquaintances in New York.

- They didn't let me feel easy.

- They said, if they offer you a job for $10 a week,

- grab it with both hands.

- But if they offer you a job for $18,

- expect the week after you are laid off.

- They don't keep you.

- So I wasn't feeling too good.

- After a week, with the bus I traveled from New York

- to Chicago.

- Stayed there with my brother.

- It was distant cousins of ours.

- The fact, their father was a cousin of our father, who

- had come to this country when he was 10 years old,

- who was living in Chicago.

- And those girls, naturally they were American born.

- They invited me for supper, and they wanted to give me a treat

- and serve me corn on the cob.

- I said no, we feed that to pigs where I come from.

- You can eat that.

- [LAUGHTER]

- And so the first thing was going hunting

- for an apartment, my brother and myself,

- finding one in an apartment building,

- furnished apartment, daily maid service, $40 a month.

- Then with my uncle was very well known in the business world.

- Me, a meat man, learned meat man.

- He sent me all to the meat packing

- houses up to Armour Company.

- But as I said, I have left Germany

- like a lord, dressed with the best clothes from head to feet.

- So when I first went to Armour Company,

- they had every day where they were showing the place

- but the tour was over.

- But when they saw me, over loudspeaker,

- there's somebody wants to see, inspect--

- they thought a visitor from the old country

- gave me a special tour just by myself to the place.

- So I saw the process of a packing house,

- from slaughtering the cattle until the process when they were

- sold the butter and cheese.

- And when I saw the process, my heart fell to my feet

- that I should work under those conditions.

- But nevertheless, a higher up gentlemen

- who knew my Uncle Charlie, my dad's cousin,

- they had a nice talk to me.

- All his encouragement was, yeah, leave your address

- and give your--

- make an application with the secretary.

- That was it.

- Then I went to a big place.

- They had all the hotel supplies, [? Selfour ?] Brothers.

- When I came there, I was led in the office.

- I told them that you fell down.

- I just come from Germany.

- I was reception.

- They want to know about the conditions

- there every night when I was through.

- Yeah, right now this is very slow

- but leave your address so and so.

- I was pretty much discouraged.

- That I was-- when I left England,

- there were people in our boarding house.

- Go and say hello.

- We have nephews in Chicago.

- And I go to those people.

- In the meantime, they were cattle dealers.

- And I said, your uncle's son says hello.

- Yeah, you say you go tomorrow morning on 46th on Halstead.

- Hygrade is opening a new plant there.

- You see there for this work.

- I take the L and go in that--

- go there, and I see there the first time a huge trailer

- unloading all of the beef.

- And I was scared to open my mouth.

- And I'm standing there and until it was all unloaded.

- And I see a guy who is scaling that.

- And I go to him and I said, listen, Mr. Worth sent me here.

- Maybe you have work for a butcher.

- That man answered not one word.

- With one hand, he opened the cooler door,

- and he called in that cooler, Stanley, here

- is a fellow who claims to be a butcher.

- Give him a hook and a knife.

- And I was standing there in my best clothes.

- And so he gives me a hook and a knife.

- They came some [? Bilko ?] customers who talked German.

- They felt very, very sorry for me.

- They want to be helpful even that.

- But they let me do piecework.

- At that time, I was a greenhorn.

- Everybody was taking advantage of me.

- Well, I worked in that place for three days.

- And after three days, I had earned $5.04.

- But in the meantime, I had made an application

- at the packing of Oscar Mayer.

- And the second week, I worked there again and made $5.48.

- I was afraid when I come home I see in the mailbox

- a notice from Oscar Mayer, I would

- like to see you at your earliest convenience, John [? Meyer, ?]

- the superintendent.

- But in the meantime, at Hygrade, that type of meat,

- I had already big infection on my finger.

- And all that night, I was bathing my finger

- and bathing my finger.

- The next morning, I go to the Oscar Mayer room,

- and I came in the office.

- And I start stuttering with my English.

- That fellow told me, you can talk German to me.

- He had come himself eight years before from Germany.

- But in the meantime, he was already superintendent.

- And then he talked to me for about an hour.

- Then he said, yeah, you go to the doctor and examine.

- And then on Monday, you can start working, not telling me

- what I would make or nothing.

- Then he turned around and he said,

- I want to introduce you to your boss.

- He introduced me to Gottfried Meyer.

- That was the nephew of the chairman of Oscar Mayer.

- Everybody was really pleasant.

- So I go to the doctor.

- Dr. Showalter, and they examined me.

- On Monday morning, I started working.

- And they put me in the boning department.

- And the others, they were cutting the meat off the bone.

- And I should just clean the bone.

- And the assistant foreman was a German fellow too.

- Already at lunchtime, I said, Frank, that is no work for me,

- cleaning the bones.

- Naturally, I talk German to him.

- And so after lunchtime, he told an American fellow,

- you clean the bone and Albert cleans the meat.

- And then that [? red ?] guy was just a greenhorn.

- He was rubbing in his beard and all, but that didn't help much.

- So I was standing there.

- But in the meat packing business,

- in May is the slowest time then, when big companies like Armour,

- Swift at that time, laid the people off, 20,000,

- 30,000 at a time, that only big people with big seniority

- keeping their jobs.

- And so it was slow at Oscar Mayer too,

- but they were very decent.

- They came then and asked me, Albert, you

- want to work in the hog-cutting floor instead laying me off.

- But at that time, it was still a 48-hour a week.

- And so they put me in that hog-cutting floor.

- But may I interrupt you?

- After a week working in that boning place and I got my check,

- I got my check $20.80, I felt like a king.

- And I worked decent.

- So coming in that hog-cutting floor,

- I had to trim, trim on slabs bacon.

- And I was wondering, you had to put

- the trimming in a barrel with your clock number on it.

- And they called the boss of that hog-cutting floor the slave

- driver.

- He only addressed me not with my name.

- I was Landsmann.

- And at five minutes to 8:00, everybody had to stand

- attention-- at attention at the table.

- At 8 o'clock, the whistle blows.

- Then with the heel of the knife, they made noise on the table.

- Everybody had to go.

- The people were scared to use the bathroom.

- They had to stay on their job.

- Then in the evening, that what you had done

- was put on the scale, your lock number and the weight on it.

- At that time, couple days later, that slave driver

- comes to me, Landsmann, can't you do any better?

- And but then I was told how much on a minimum

- you had to do in order to be able that they keep you,

- to hold your job.

- But then I found out I did already one fourth more

- than it was required to do.

- But that other boy, he was a Polack, a slave driver.

- No, maybe he wasn't a friend of the Jews either.

- And so I worked in that place only 28--

- 28 hours a week.

- I don't remember after a week or two on a Friday, he comes to me.

- And he said, Landsmann, you want to work tomorrow

- for your first boss, Mr. [? Schaefer? ?]

- That was the big boss from the boning department

- as well from the wholesale department.

- He was a German fellow too.

- And I said, a poor devil has to work.

- He thought maybe for Shabbos I didn't.

- OK, you go then there.

- The next morning, I go in that wholesale department.

- And they had there so many offals.

- And they pulling, pulling, trying

- to take so many barrels and barrels and barrels.

- And as I said, I was 100% expert.

- I didn't have to learn the trade here.

- And I worked there.

- And when it was early afternoon, I

- saw them sticking their heads together,

- another fellow worker or another boss.

- Then that Mr. [? Schaefer ?] came to me.

- And he said, Albert, don't you want to work for me here?

- What do you have to work for that slave driver?

- And you don't work 28 hours.

- You work as long as you want to work.

- You can work 48 hours.

- You work as long as you want to work.

- See, they never was used to somebody working like I worked.

- And for sure, I worked.

- So the next morning, Monday morning, that slave driver,

- in order to go to this hog-cutting floor,

- he had to pass my place.

- And he sees me working there.

- Landsmann?

- Nanu?

- I said, yeah, I'm working.

- I will see to it-- having a good man

- and taking that away from me?

- Before I was not good enough, I was not fast enough.

- But anyhow, I stayed in that place.

- And I said, I had started there with Oscar Mayer with $0.50

- an hour.

- You had to belong to the union.

- After I was four months there, a fellow worker said, Landsmann,

- how much money you make?

- I said $0.50.

- That's not right.

- You are entitled for after three months

- and they don't lay you off, you're

- entailed for a nickel more.

- So I go to the office, and I say what about it?

- Your next paycheck, you get it.

- Then after two months, I got an additional 7 1/2 cents raise.

- I got then 62 and 1/2 cents.

- But in the meantime, I stayed in that wholesale department,

- the same way wholesale that I was

- used to work at home in our own business.

- And you heard my name 100 times over that mic.

- And in the fifth floor was the freezer.

- I called the fifth floor for an order.

- But I talked German.

- Then other people came from the boss of the shipping.

- What is the matter?

- Are we here in America or in the old country?

- Because they couldn't participate what

- I was talking about.

- But anyhow, I--

- Then as I said I got 62 and 1/2 cents.

- Then automatically we got a raise to 67 and 1/2 cents.

- And there were people that were working there for 30 years that

- were making $0.90 an hour.

- And well, let me skip a little bit.

- I was there exactly 11.5 months.

- I was at that time, from over 700 people,

- among the three best paid people in the plant.

- Then in the meantime, the war-- as I said, the war broke out.

- And I had to go and register.

- And at that time, your examination

- was still before an individual.

- That was in Hyde Park.

- And he talked to me, start on my head.

- You become a good soldier.

- And he said, take your pants down.

- And he said, pick them up.

- You have a rupture.

- You know, they don't take you.

- But you better tell your people.

- So I got the classification 4F.

- I go, tell the boss about what they told me.

- They sent me back to that Dr. Showalter,

- and he examined me and he called the assistant.

- You have no rupture.

- But anyhow, I kept on working.

- I had my number was--

- I had a very low registration number.

- And finally they got a notice from the draft board,

- concerning them.

- He said, yeah, so and so, you have to go for examination.

- I said, I had my examination.

- It makes no difference, rupture or no rupture.

- So I had to go before the old specialists who examined you,

- and nobody told me anything if I had a rupture or no rupture.

- After a few days, I got in a notice, re-classified, 1A.

- And then my brother, who was living with me,

- I guess I had 4,000 registration number.

- My brother had 10,000 or whatever it was.

- And he said, yeah, the war has to take a long time

- until before they call me.

- So I was in call to go downtown Chicago,

- and all examinations again and nothing.

- But in the afternoon, I was in the army.

- But I could ask for two weeks to straighten out things.

- And it was then I had to report in November '42.

- I had my basic training in Camp Grant, Illinois.

- My brother who had that high number,

- he was inducted nine days after me.

- Went from Camp Grant, came to Camp Carson.

- Today, it's called Fort Carson, Colorado.

- Then to the Thermal Air Base in California

- near Indio, California.

- From there back to Camp Carson, Colorado.

- Then back to Barkeley Texas.

- Then in November, '44 we were shipped overseas.

- It's a week later now, and it's May 6, 1981.

- And we're speaking to Mr. Albert Geisel again this morning.

- And we're going-- since we talked a little bit

- about to the point where you were in the Second World War

- and in Europe.

- Now we'll go over that area lightly

- and see what happens and come back to the United States

- eventually.

- We left from Boston and converted SS America

- to Scotland.

- And we had Thanksgiving near Glasgow in old barracks

- from World War number one.

- After being there for a few weeks, we went with the railroad

- through England to Southampton, crossed the Channel,

- and arrived in France, in Le Havre.

- There we struck.

- We went to a place, Étretat, a former resort

- on the English Channel.

- And there we stayed-- we had--

- we stayed there for a short time.

- Then it was when the Battle of the Bulge

- started when Von Rundstedt made that advance.

- We left Étretat to [? Villejuif, ?]

- a suburb of Paris where we took over a French hospital.

- And there we were very busy, but those casualties which

- we got there were tremendous.

- As it was in the middle of winter,

- the biggest casualties were--

- And we are rerecording some previous tape that was--

- something unfortunate happened to.

- And today is June the 10th, 1981.

- And we're going to start, hopefully,

- where we left off last time at the end of that tape.

- And we got to the point where we were talking

- about how you met Mrs. Geisel.

- Do you want me?

- How did you meet your--

- Mrs. Geisel?

- This is actually a long story or not a long story.

- During the war, my parents and sister were in London, England.

- And my brother was attending--

- the university-- was sent from the army

- to attend the University of Cincinnati

- in order to learn French.

- And as it was done of so many Cincinnati families on weekends,

- they invited GIs.

- And so my brother was invited from a family, Carl Frank,

- for a weekend.

- And there came the conversation that Carl Frank

- had a sister who was not married and were in England.

- And my brother said, I have an unmarried brother

- who is in the army.

- And that was it.

- But after the war, I was with my--

- I was discharged from the army.

- And I was with my mother in New York, where I had taken a job.

- And one day, I was called home.

- My later wife came with her brother and sister-in-law

- to visit an acquaintance who had been in England also

- and were also acquaintances of my future wife to look me up.

- And then after, they left New York for Cincinnati.

- In the meantime, my brother had had his discharge too

- and were living in Chicago.

- And between my later brother-in-law, Carl Frank,

- and my brother, Gus Geisel, they arranged

- that I should meet Elsa.

- And in the meantime, I had a very, very good-paying job

- in New York.

- But they were after me.

- I had a much better future in Cincinnati.

- And so we got to the decision that I married, and started,

- and came to Cincinnati.

- For a very short time, it was in the business

- with my brother-in-law.

- What business was that?

- He had a sausage factory.

- And he wanted to enlarge.

- I-- as it was, my life going 100 percent in the hotel supply

- business.

- But for one reason or the other, I

- was not too happy when I started in business for myself.

- That was in March 1947.

- When you moved to Cincinnati, what part of the city

- did you move to?

- First, my brother-in-law, he lived on Cleveland Avenue.

- And we moved in to the third floor in his house--

- I don't know how many months.

- Then, also on Cleveland Avenue, there was a house for sale

- from Lillian's wife.

- The first few months in Cincinnati,

- she works there as a fitter or a seamstress,

- whatever you call it.

- And that house belonged to--

- they'd call her, I guess the grandmother,

- the mother of Mr. Jacobs or whatever it was.

- And so we bought that house in order

- to be close to the relatives.

- And at that time, Cleveland Avenue

- was very convenient located.

- As a fact, my wife doesn't drive.

- And we had our business in Bond Hill.

- But when our son became school age--

- Do you just have one son?

- One son.

- And he was born here in Cincinnati?

- Born in Cincinnati.

- We married in October '46, and our son was born in October '47.

- That was good.

- And we-- one day, I saw a house advertised in Bond Hill.

- And a friend of my brother-in-law,

- who was a builder, I took him along to look at the house.

- And I was ask the price.

- I made right away an offer.

- Also, the builder said, Albert, take it easy.

- Was on a Sunday afternoon, and I went home.

- We had a little to eat.

- Then it happened.

- The doorbell rang.

- And somebody came in the door, inquired

- for some certain people.

- And while I was talking there, I talked to our neighbors.

- Then I was called from my wife.

- I'm wanted on the phone.

- And the seller of the house was on the phone

- and said, Mr. Geisel, we did some talking

- and some arithmetic.

- I accept your offer.

- And what street was that now?

- On Yarmouth Avenue, Bond Hill.

- At that time, Bond Hill was one of the top elementary schools.

- But as I said, our son was in walking distance,

- wasn't depending on transportation going to school.

- And my wife was in walking distance to the business,

- as she doesn't drive.

- So it was very, very convenient located for us.

- And I don't even recall if we stayed in Bond Hill--

- maybe from 1952 to 1976, I guess.

- When we sold our house, as we are-- in the meantime,

- our son got married.

- And this was only my wife and myself.

- We didn't need a house.

- And we saw a nice place advertised.

- And we moved to Roselawn, our present location.

- Your present home.

- All right.

- Let's go back.

- And I think would be interesting to talk about the business.

- We didn't-- we erased that part from the first tape.

- As I said, I started out in business.

- At that time, it was very difficult.

- It was very competitive.

- And at that time, I didn't know, the predecessor of my store

- was very much disliked as, during the war,

- he took too much advantage of people.

- He was able do his relationships with meatpackers

- that he had enough meat to sell, but sold it only

- to friends or at known high prices.

- So when I bought the store, it was a declining business,

- as that man was so disliked.

- So I had to start all over again.

- But as business progressed, I got very well-known.

- I didn't have to do too much advertising

- because my best advertising was from our customers,

- from mouth to mouth.

- And I must say, I was 100% expert in my line.

- I could serve the people with the right merchandise

- and the right price, without taking advantage of them.

- The store was on California Avenue, wasn't it?

- The store was on California Avenue,

- next to Fifth Third Bank.

- And later on, as people went more and more to freezer meat,

- I was approached from all my customers,

- filled their freezer with sides of beef, and so--

- and developed till that became a nice restaurant supplier.

- My business was lately only 90% or maybe even 95% in meats.

- And from the 95%, was 75% wholesale.

- But as our son had left and went to college,

- and after reaching 65, my wife didn't want to work anymore.

- So when I was almost 66, I sold our place and retired.

- OK.

- Let's talk about, now, your religious and social life

- in the Cincinnati community.

- When you first came to Cincinnati,

- you were a young married man.

- What was your social life?

- Was it primarily your family?

- First of all, you came out of the army,

- you had left the old country.

- Also, coming from a very wealthy family,

- you started out with nothing.

- But I always was independent and want to be independent.

- There was not an eight-hour day, that was a 15-hour day and six

- and a half days a week.

- And so there was not much left what social life concerned.

- And at that time, the newcomers, what religious life concerned,

- they joined the New Hope congregation.

- And naturally, only on the High Holidays,

- you could participate in the service.

- But later on, when our son became school age,

- all his friends were--

- belonged to the Wise Temple.

- And so naturally, I made an appointment.

- At that time, it was--

- Milton Bloom was the president of Wise Temple.

- On a Sunday, I had an appointment with him.

- And I said, so and so.

- And I joined the Wise Temple.

- And so later on, we were only just

- a paying member of New Hope.

- But we attending all the activities and services

- with the Wise Temple because also, we were so-called Orthodox

- Jews in the old country.

- But nevertheless, we didn't know the translation from Hebrew

- to German, or in this country, from Hebrew to English.

- But at the Wise Temple the service

- was conducted in English.

- So we could follow the service.

- And we could understand what we were praying.

- But while with the Wise Temple, naturally,

- when there came Passover, we always--

- second day, we participate in the congregational Seder.

- Otherwise, our social activities were very much limited,

- as mentioned before, with six and a half days work

- and 15 hours or more a day.

- So now, you're making up for it now.

- Have you ever returned to Germany?

- Yes.

- In '72, when I retired, we--

- there was a special flight from the Germania.

- And my wife and myself, with quite a few of my--

- our acquaintances went on the same flight.

- And we went direct from Cincinnati

- to Frankfurt, where I rented a car, and from Frankfurt,

- going to my hometown, Rheinbach.

- That was about 150 kilometers.

- Well, it's German.

- But nevertheless, they had now the Autobahn--

- that means the expressway--

- when I came.

- I should have--

- I made a mistake.

- I was looking for the word exit where

- I had to leave in Siegburg.

- But in German, it is not exit, it is Abfahrt.

- But nevertheless, I made some detour.

- But I had to go from the Autobahn, which

- is on the right side of the river Rhine.

- I had to go across the bridge to Bonn.

- And from Bonn was the main highway,

- Meckenheim, and then Rheinbach.

- That was dramatically different.

- It was dramatic.

- I had to ask my way through.

- But after being in Rheinbach, I was at home again.

- What was it like when you got back there?

- So we went there to a restaurant where

- my brother had stayed before.

- We had been in the old country more frequently as I was.

- And I made reservations.

- But it was on a Sunday afternoon after putting our luggage

- in our room.

- But it was making one mistake.

- From leaving that restaurant, I want

- to see our friend, close friend, who is a farmer in Rheinbach,

- but just a couple of minutes from that restaurant.

- And I took the key from our apartment wrong.

- And leaving the restaurant, instead hanging it up that

- people knew that I had-- that I was not in the building,

- I went to our friend's.

- And that is custom in a small country

- town in the Sunday afternoon, they visit the cemetery.

- And saw my friend's daughter and family

- who live in the same building, who didn't know us.

- But they heard my parents are at the cemetery.

- In the meantime, it was about 4:30 in the afternoon.

- I showed my wife around in the city and explained a little.

- While walking around, in the meantime,

- the people were leaving church.

- And there was one couple, second house neighbor of ours,

- Jacob [? Kriebler ?] and Betty [? Kriebler. ?] And that man was

- in the upholstery business.

- They're walking towards me.

- And I step in front of them.

- And I ask them, don't you know me?

- No.

- I said, aren't you Jacob [? Kriebler. ?] Yeah.

- Aren't you Betty?

- She was used to be in my class.

- She went to school with me.

- That Jacob [? Kriebler ?] was two years older than I am.

- I said, don't you know Albert Geisel?

- Then you can imagine the surprise.

- Then all those people--

- and there's a small town, that was in the middle of the city,

- came from church.

- And then everybody came.

- Yeah, here's my sister, Clara.

- Here's this and that.

- But as it was so long, I mean, it took me a long time

- to remember that yeah, there's [? Gemur ?] [? Chang. ?]

- There's [? Franz ?] [? Hank ?] and so on.

- I mean, then I got acquainted.

- Anyhow, after talking to them, we went then across the street

- where we used to live.

- There was a restaurant.

- And I said to my wife, let's eat a little.

- While eating there, I--

- my former friend, the Jacob [? Kriebler ?] was there.

- And I treated him for a glass of beer and talking to him.

- In the meantime, on the other table were four or five people.

- And so my friend said, don't you know Willie [? Storm ?] anymore?

- And so going over there, the right away,

- so many questions they bring.

- And one sister from-- of that [? Willie ?] [? Storm, ?] she

- went to school with my brother.

- So all the questions about how I've been and all the experience

- what I had in concentration camp,

- and all they claimed they didn't--

- They were interested to know.

- --they didn't know anything about it.

- But our conversation took so long that in the meantime,

- it was 8:30 when I walked in to the place of my friend,

- [? Arnold ?] [? Simmons ?] and family, that farmer.

- And while I was there, the neighbors came.

- And everybody was holding ears and mouths

- open to want to know so-and-so.

- And that was extended and extended.

- In the meantime, there was the son

- of a former next-door neighbor.

- He lived across the street of that friend of ours.

- Yeah, we have to see Willie [? Esse ?] too.

- So we go then to him.

- And right away, they came and bottle of wine.

- And his wife, she was a daughter of a former customer of ours.

- But when I had left Germany, she was maybe three, four years old.

- She had no idea.

- And when we had a conversation about her aunt and uncle,

- and they were only sitting there and so

- amazed how I all know the family conditions.

- But in the meantime, I guess it was about 12:30 at night.

- And we had not slept with the time difference,

- for maybe 18-19 hours leaving the United States.

- And we coming to our restaurant.

- We had in front, that whole thing was with a gate closed up.

- And we couldn't get in.

- And we rattled on that gate.

- You could hear at night, when everything

- was quiet for 10 miles.

- We couldn't get in.

- And so what really happened in the--

- at that day, there was Schützenfeste in the city.

- It was the same then, the blank--

- I know it-- it's like the Coping House has once a year here

- in Cincinnati.

- I think that's wine and dancing.

- When they shoot the bird, and so on, and so on.

- And so everybody was attending there

- in the outskirts of the city.

- And they thought.

- And then so what did we do?

- We tried to get in another hotel to sleep.

- But everything was closed.

- So finally, we went back to that farmer.

- I slept between two chairs.

- And so the next morning, when I went into our restaurant,

- and those people were amazed to see us.

- They thought we were in our room.

- Then our key was not hanging up.

- So that day, we walked around and saw another friend

- of ours, a lady--

- the fact, she had visited me in London

- while I had waited a year in London for my quota number

- to come to the United States.

- And after that, in the afternoon, we met our friends.

- And with our car, we went for a tour what

- I was used to do to Altenahr, Neuenahr, what

- is a very famous resort town, and then down the river

- Rhine, then up Bad Godesberg.

- And then in the meantime, we pass

- a village for our friend's daughter-in-law was married.

- With our car, we went into the field where there were--

- So you had a very wonderful experience and good feelings

- about going back to Germany then?

- And then the next day, as we had--

- what was wrong on our part, we had arranged our tour,

- we left our hometown to Brussels, Belgium,

- to see my uncle, who was living there.

- And so we stayed about two or three days with our uncle

- in Brussels.

- Then we, with our car--

- and he and his wife with his car--

- we went to La Rochelle in Luxembourg.

- They called that the Luxembourg Swiss.

- It is located in very nice, green pasture country.

- We stayed there with them for three days.

- And from there, we took the car, we

- left Luxembourg, and went to--

- over Metz, to Strasbourg in France, where

- a cousin of my wife was living.

- We stayed with her a few days in Strasbourg.

- With friends of them, we went all to the surroundings.

- We went to the Borges that is--

- was very well-known from World War I,

- where were heavy fighting done.

- From there, we went--

- but it was all close by to Baden-Baden, very famous

- resort town.

- And after going back, then, a few more days to Strasbourg,

- we left Strasbourg, and went to Freudenstadt,

- and stayed there for six or seven days.

- But besides going to the [? cool ?]

- garden, listen to the music, the band,

- we went several times again to Baden-Baden.

- And I drove my wife to the vineyards

- what she never had seen before.

- Where was your wife actually from originally?

- She came--

- Cologne, did you say?

- She came from north Germany, Wunstorf-- that's near Hanover.

- And then after six days in Freudenstadt, our time was up,

- we drove to Frankfurt, turned our car in,

- and back to the United States.

- So how was your general impression of your return?

- As I said, it was my--

- as I was only such a short time in Germany,

- had no much chance to talk to people.

- But in my hometown, which was only a town of 5,000

- population--

- but while I was gone, Germany had lost World War II,

- the population had doubled as the people from former Sudeten

- Germany, with their industry, had come to Germany so that

- there wasn't a population of 5,000 people,

- there were 10,000 people.

- In my hometown, much buildings going on what

- had been gardens and fields.

- There were houses.

- Like city hall, what was in the middle of the city,

- that was built outside of the city.