Overview

- Brief Narrative

- Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 100 [hundert] kronen note owned by Hildegard and Moritz Henschel who were interned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German occupied Czechoslovakia from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz and Hildegard were Berlin residents when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany which was forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association. When it was shut down on June 10, 1943, Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

- Date

-

received:

after 1943 June

issue: 1943 January 01

- Geography

-

issue:

Theresienstadt (Concentration camp);

Terezin (Ustecky kraj, Czech Republic)

- Credit Line

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection, Gift of Yoel Givol and Michal Lilli Kahani, in memory of their grandparents, Hildegard and Moritz Henschel

- Markings

- face, upper center, brown ink : QUITTUNG ÜBER / HUNDERT KRONEN / 100 [RECEIPT OF / HUNDRED CROWNS]

front, lower center, smaller text than above, brown ink : WER DIESE QUITTUNG VERFÄLSCHT ODER NACHMACHT / ODER GEFÄLSCHTE QUITTUNGEN IN VERKEHR BRINGT. / WIRD STRENGSTENS BESTRAFT [ANYONE WHO FALSIFIES OR DISTORTS OR FAKES THIS RECEIPT, OR COUNTERFEITS RECEIPT, WILL BE STRICTLY PUNISHED]

reverse, upper left, serial number, red ink : 005430

reverse, lower right, series letter, red ink :

reverse, lower left and upper right, brown ink : 100

reverse, center, brown ink : Quittung / über / HUNDERT KRONEN / THERESIENSTADT, AM 1.JANNER 1943 DER ALTESTE DER JUDEN / IN THERESIENSTADT [Receipt / of / HUNDRED CROWNS / THERESIENSTADT, ON 1. JANUARY 1943 THE ELDER OF THE JEWS IN THERESIENSTADT] - Contributor

-

Subject:

Hildegard Henschel

Subject: Moritz Henschel

Printer: National Bank of Prague

Designer: Peter Kien

Issuer: Der Alteste der Juden in Theresienstadt

- Biography

-

Hildegard Alexander was born on April 29, 1897, in Berlin, Germany. During World War I (1914-1918), she served as a nurse for the German Red Cross and was awarded a medal for her service. She worked as a lab technician at a pharmacy company from 1919 to 1923. On June 28, 1922, she married Moritz Henschel, who was born on February 17, 1879, in Breslau, Germany. They had two daughters: Marianne, born on September 6, 1923, and Lilly, born on April 5, 1926.

In January 1933, Hitler came to power and, by summer, Germany was ruled by a Nazi dictatorship. As living conditions worsened for Jews, Hildegard and Moritz decided to get their daughters out of Germany. In November 1938, they sent Marianne to a Zionist preparatory camp in Rudnitz. On January 31, 1939, Marianne, 15, emigrated to Palestine with a Youth Aliyah group and settled in a kibbutz. Lilly, 13, was sent to England on a Kindertransport in 1939. Moritz served on the board of the Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland (The Reich Association of Jews in Germany), and became the president of the Berlin Kehillah (Jewish Community) in March 1940. Hildegard worked for the Reichsvereinigung Office of Emigration from 1939 to 1940, then as a secretary for the Jewish Community’s health administration. On September 19, 1941, they were forced to wear Star of David badges. The government began confiscating Jewish property, starting with an old age home. Hospitals and schools were also confiscated. The conditions in Berlin worsened as the government pursued the policy of making Berlin Judenfrei (free of Jews). In October 1941, the Nazi government began large scale deportations of Jews from Berlin. The Reichsvereinigung was forced to assist with the deportations. Moritz believed that cooperation was necessary because they would carry out the deportations more humanely than the Germans. As the deportations increased, the number of Jewish suicides increased. Every case was taken to the hospital where Hildegard worked and she kept track of the rising numbers. Moritz eventually learned that he was being lied to about the destination of the transports and that people were being killed. Moritz and Hildegard were protected from being deported because they were employees of the Jewish Community and had special identification. They wore their Star of David badges on the left and had a stamped armband. In January 1943, Moritz became the president of the Reichsvereinigung after the former president was deported.

On June 10, 1943, the German SS closed the Reichsvereinigung. Hildegard, Moritz, and the remaining leaders of the Reichsvereinigung were arrested and taken to an assembly camp in Berlin. On June 16, Hildegard and Moritz were deported to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp. Moritz was elected to the Judenrat (Jewish Council) and was put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung (Leisure Time Department), which produced cultural materials and events, such as music, poetry, and plays. Moritz was also made head of the post office. The camp was overcrowded and severely lacking in food. Death from disease and starvation was common. Hildegard and Moritz survived by receiving food parcels from Sweden and keeping a low profile. They were liberated on May 9, 1945, by Soviet forces.

In fall 1945, Hildegard and Moritz went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp in Germany. In 1946, they immigrated to Palestine and settled in Tel Aviv. Moritz was in poor health and died at age 68 on April 22, 1947, in Tel Aviv. On May 11, 1961, Hildegard testified in the trial of Adolf Eichmann and discussed her experience in wartime Berlin and Moritz’s position in the Jewish Community. Eichmann, as chief of Reich Security Main Office department IV B 4 (Jews). was responsible for organizing the mass deportations of Jews to concentration camps and killing centers. The trial was televised and attracted worldwide attention as the first detailed, public examination of the evidence and atrocities committed during the Holocaust. Eichmann was found guilty at the trial and executed in 1962. The trial experience was very difficult for Hildegard and she never spoke about the Holocaust again. Her daughter Lilly died in 1962. Hildegard, 86, died in 1983 in Israel.

Moritz Henschel was born on February 17, 1879, in Breslau, Germany (Wroclaw, Poland), to Karl and Emma Deutsch Henschel. In January 1910, he graduated from the Berlin Rabbinical Seminary and began working as a lawyer. Moritz served in the German Army in World War I (1914-1918), and was awarded the Iron Cross, Second Class, for bravery. After the war, he worked at the Landgericht, the regional court in Berlin. On June 28, 1922, Moritz married Hildegard Alexander, who was born on April 29, 1897, in Berlin. She served as a nurse in World War I and worked as a lab technician at a pharmacy company from 1919 to 1923. They had two daughters: Marianne, born on September 6, 1923, and Lilly, born on April 5, 1926.

In January 1933, Hitler came to power and, by summer, Germany was ruled by a Nazi dictatorship. Moritz was a member of the Reichsvertretung der Deutschen Juden (Reich Representation of German Jews), which was established in September 1933 to oversee Jewish education, vocational training, welfare and economic assistance, and emigration and was an influential member of the Berlin Kehillah (Jewish Community). On March 5, 1938, the Jewish Community was no longer recognized by the Nazi government as a public corporate body, so Moritz, along with Heinrich Stahl and Herbert Selinger, ran it as an emergency committee. As conditions worsened, Moritz and Hildegard decided to get their daughters of Germany. In November 1938, they sent Marianne, 14, to a Zionist preparatory camp in Rudnitz. On January 31, 1939, Marianne left for Palestine with a Youth Aliyah group and settled in a kibbutz. In 1939, Lilly, 13, was sent to England on a Kindertransport. In February 1939, the Reichsvertretung was restructured into the Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland (Reich Association of Jews in Germany), which oversaw Jewish emigration, education, labor, and welfare. Moritz was on the board. Hildegard worked for its Office of Emigration from 1939 to 1940. In August 1939, the Berlin Jewish Community was reorganized as a society under the Reichsvereinigung, with Heinrich Stahl as president. In March 1940, Moritz became president of the Jewish Community when Heinrich Stahl was removed by the government. Hildegard was a secretary for the Community’s health administration. On September 19, 1941, Jews in Berlin were forced to wear Star of David badges. The government began large scale confiscations of Jewish property, starting with an old age home. Hospitals and schools were also confiscated.

Living conditions for Jews worsened as the government pursued the policy of making Berlin Judenfrei (free of Jews). In October 1941, the government began large scale deportations of Jews from Berlin. The Reichsvereinigung was forced to assist with the deportations. On Yom Kippur on October 1, Moritz and two of his employees were taken from the synagogue to meet with the Gestapo. They were told that a large number of people were being deported to Łódź. The Jewish community had to submit an updated list of all Jews in Berlin and turn one of the synagogues into a transit camp for 1,000 people. After 4,000 people had been deported, Moritz was told the next transports would be sent to a kibbutz near Riga and Minsk. He believed that cooperation was necessary because they would carry out the deportations more humanely than the German SS. Moritz had secret contacts in the railroad and they soon realized that they were being lied to about the destination of the transports. They received news that people were being moved from Łódź and Riga to Stutthof concentration camp, where they were killed. They never heard about the transport to Minsk again. The government eventually established more assembly camps in Jewish cemeteries, hospitals and synagogues, from which Jews were deported to eastern Europe. The deportations increased, but Moritz and Hildegard were protected from being deported because they were employees of the Jewish Community and had special identification. They wore their Star of David badges on the left and had a stamped armband. After the president of the Reichsvereinigung, Leo Baeck, was deported to Theresienstadt in January 1943, Moritz became president.

On June 10, 1943, German SS went to Moritz’s office and arrested him, telling him that the Reichsvereinigung no longer existed. Moritz, Hildegard, and the remaining leaders of the Reichsvereinigung were taken to an assembly camp in Berlin. On June 16, Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German occupied Czechoslovakia. Moritz was elected to the Judenrat (Jewish Council). The chairman of the Judenrat reported to the German camp commandant and administered the camps for the Germans. He was advised by the members of the council. Moritz was put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung (Leisure Time Department), which produced cultural materials and events, such as music, poetry, and plays. Moritz was also made head of the post office. The camp was overcrowded, with severe food shortages, and disease and starvation were widespread. Moritz and Hildegard survived by receiving food parcels from Sweden and keeping a low profile. They were liberated on May 9, 1945, by Soviet forces.

In fall 1945, Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp in Germany. In 1946, they were given permission to immigrate to Palestine and settled in Tel Aviv. On September 13, 1946, Moritz gave a lecture about the last years of the Berlin Jewish Community. Moritz, age 68, died on April 22, 1947, in Tel Aviv.

Franz Peter Kien was born January 1, 1919, in Varnsdorf, Czechoslovakia (Czech Republic), to Leonard and Olga Frankl Kien. His father Leonard was born in 1886, in Varnsdorf, and was a member of the German-speaking Jewish population in the, the Sudetenalnd, which bordered Germany. Leonard was a textile manufacturer with his own factory. Peter’s mother Olga was born in 1898, in Bzenec, Austro-Hungary (Czech Republic), to Jewish parents. After 1929, the Kien family moved to Brno. Peter enrolled at the German Gymnasium, where he excelled at drawing, painting, and writing. In 1936, he graduated and moved to Prague to study at the Academy of Fine Arts. He also attended the Officina Pragensis, a private graphic design school run by a well-known Jewish artist, Hugo Steiner-Prag.

On September 29, 1938, Germany annexed the Sudetenland. On March 15, 1939, Germany invaded Prague and annexed the Bohemia and Moravia provinces of Czechoslovakia, ruled by a Reich Protector. Jews were banned from participation in government, businesses, and organization, including schools. Peter had to leave the Academy, but continued to study at the Officina Pragensis. He also taught at Vinohrady Synagogue. In September 1940, Peter married Ilse Stranska, who was born on May 9, 1915, in Pilsen, to Jewish parents.

In late September 1941, Reinhard Heydrich, the SS head of RSHA, Reich Main Security Office, became Reich Protector. Soon there were regular deportations of Jews to concentration camps. At the end of November, Theresienstadt concentration and transit camp near Prague got its first shipment of Jewish prisoners. On December 14, Peter was transported to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp. He was assigned to the technical department where he worked as a draftsman and designer alongside other artists, including Bedrich Fritta, Leo Haas, and Jiri Lauscher. On July 16, 1942, Peter’s wife Ilse arrived in the camp. On January 30, 1943, Peter’s parents Leonard and Olga were transported from Bzenec to Terezin. Peter was assigned major projects by the Jewish Council that administered the camp for the Germans, such as the scrip receipts used in place of money in the camp. He secretly documented the inmate’s daily life, creating portraits and other drawings, and wrote plays, poems, and an operatic libretto. On October 16, 1944, Peter’s wife Ilse and his parents Leonard and Olga were selected for deportation. Peter volunteered to go with them. Before leaving, Peter and his family were sent to Auschwitz concentration camp in German-occupied Poland. Peter survived the selection process, soon fell ill, likely with typhus, and died at age 25 in late October 1944. His wife and parents were killed at Auschwitz. Some of the work that Peter left with other prisoners or hid at Theresienstadt survived and has been exhibited worldwide.

Physical Details

- Language

- German

- Classification

-

Exchange Media

- Category

-

Money

- Object Type

-

Scrip (aat)

- Extent

-

1 book.

- Physical Description

- Theresienstadt 100 kronen scrip printed on rectangular, watermarked, offwhite paper in black, orange, and red-brown ink. The face has a vignette of Moses, a bearded man with a wrinkled brow, holding 2 stone tablets with the 10 Commandments in Hebrew. To the right is the denomination 100 and German text. The background rectangle has an abstract, repeating pattern. On the right is a wide offwhite border with 100 in the bottom corner below a Star of David. The reverse has a background rectangle with a zigzig pattern with an underprint flourish, overprinted with German text, an engraved signature, and a scrollwork line. The denomination 100 is in the upper right corner. On the left is a wide offwhite border with 100 in the bottom corner below a Star of David in a lined circle. The serial number in red ink is in the upper left corner. The series letter in red ink is in the lower right. Scrip appears unused.

- Dimensions

- overall: Height: 3.000 inches (7.62 cm) | Width: 5.875 inches (14.923 cm)

- Materials

- overall : paper, ink

Rights & Restrictions

- Conditions on Access

- No restrictions on access

- Conditions on Use

- No restrictions on use

Keywords & Subjects

- Topical Term

- Concentration camp inmates--Czech Republic--Terezín (Ústecký kraj) Deportees--Germany--Berlin. Holocaust, Jewish (1939-1945)--Czech Republic--Terezin (Ustecky kraj) Holocaust, Jewish (1939-1945)--Germany--Berlin. Holocaust survivors--Israel--Tel Aviv. Jews--Persecution--Germany--Berlin. World War, 1939-1945--Germany--Berlin.

Administrative Notes

- Legal Status

- Permanent Collection

- Provenance

- The scrip was donated to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in 2003 by Yoel Givol and Michal Lilli Kahani, the grandchildren of Hildegard and Moritz Henschel.

- Funding Note

- The cataloging of this artifact has been supported by a grant from the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany.

- Record last modified:

- 2023-06-09 13:25:26

- This page:

- https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn544002

Download & Licensing

In-Person Research

- By Appointment

- Request 21 Days in Advance of Visit

- Plan a Research Visit

- Request to See This Object

Contact Us

Also in Hildegard and Moritz Henschel collection

The collection consists of artwork, medals, Star of David badges, books, correspondence, documents, and musical scores relating to the experiences of Moritz and Hildegard Henschel before and during the Holocaust in Berlin, Germany, during the Holocaust in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp, and after the Holocaust in Israel.

Date: 1840-1999

Moritz and Hildegard Henschel papers

Document

Moritz and Hildegard Henschel papers consist of documents, poems, photographs, correspondence, clippings, articles, and sheet music pertaining to Moritz Henschel’s role as director of the “Freizeitgestaltung,” in Terezin and his wife Hildegard Henschel’s experiences during this same time period. Moritz and Hildegard Henschel biographical and Theresienstadt materials include birth and marriage certificates, Red Cross correspondence, employment records, awards, medical records, poems, music, reports, identification papers, personal narratives, and clippings documenting Moritz and Hildegard Henschel, their deportation to Theresienstadt, their cultural and work life in Theresienstadt, and their liberation. Henschel family correspondence include prewar, wartime, and postwar family correspondence with Moritz and Hildegard Henschel, their daughter Lily, and Marianne Givol. Research materials acquired at the Terezin memorial document Peter Kien. Family photographs document Moritz and Hildegard Henschel and the Jewish council at Theresienstadt. Additional award decorations and certificate document Shmuel Givol Gotthold.

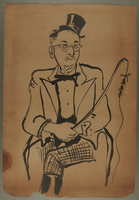

Drawing of Jewish Council member as circus ringmaster drawn by camp inmate

Object

Caricature drawn by Peter Kien for Moritz Henschel while both were imprisoned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp. It depicts Moritz as a circus ringmaster. Moritz was a member of the Jewish Council in the camp and Kien was an influential artist and playwright who also designed the camp currency. Kien was deported to Auschwitz in October 1944 and died soon after arrival. Moritz was an influential lawyer in Berlin when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As the government persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany, created by the Nazi government in February 1939 to organize Jewish affairs. The Association was eventually forced to assist with deportations. Moritz also became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association, when Leo Baeck was deported. On June 10, 1943, the Reich Association was shut down and Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt on June 16. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural materials and events. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Jo Spier watercolor of people dancing through a gate and given to another inmate

Object

Watercolor drawing created by Jo Spier and given to Moritz and Hildegard Henschel while they were imprisoned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp from June 1943-May 1945. It shows people dancing through a stone gate, leaving behind a trail of Star of David badges. Spier, a Jewish artist from the Netherlands, was arrested for creating a satirical cartoon of Hitler in 1943 and deported to Theresienstadt with his wife and three children. They returned to Amsterdam after liberation. Moritz was an influential lawyer in Berlin when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As government persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany, created by the Nazi government in February 1939 to organize Jewish affairs. The Association was eventually forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association, when Leo Baeck was deported. On June 10, 1943, the Reich Association was shut down and Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then immigrated to Palestine in 1946.

WWI Red Cross merit medal, 3rd class awarded to German Jewish woman

Object

German Rothe Kreuz [For Merit in the Red Corss] medal, 3rd class, awarded to Hildegard Alexander for her service as a nurse in World War I (1914-1918). See 2003.361.19 for the Rothe Kreuz ribbon she was also awarded. Her husband, Moritz Henschel, had been decorated for his service in the German Army during the war. Moritz was an influential lawyer in Berlin when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As government persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany, created by the Nazi government in February 1939 to organize Jewish affairs. The Association was eventually forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association, when Leo Baeck was deported. On June 10, 1943, the Reich Association was shut down and Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Iron Cross, 2nd class, 2 ribbons, and box awarded to a German Jewish soldier for bravery in WWI

Object

Iron Cross 2nd Class medal awarded to Moritz Henschel for his bravery on August 14, 1915, on the Italian front in World War I (1914-1918.) Moritz was an influential lawyer in Berlin when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As government persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany, created by the Nazi government in February 1939 to organize Jewish affairs. The Association was eventually forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association, when Leo Baeck was deported. On June 10, 1943, the Reich Association was shut down and Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Star of David badge imprinted Jude worn by a German Jew

Object

Star of David badge worn by Moritz or Hildegard Henschel who were deported from Berlin to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in June 1943. Moritz was an influential lawyer in Berlin when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As government persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany, created by the Nazi government in February 1939 to organize Jewish affairs. The Association was eventually forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association, when Leo Baeck was deported. On June 10, 1943, the Reich Association was shut down and Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Drawing of woman scrubbing floor given to German Jewish inmate

Object

Color drawing of a woman washing the floor given to Hildegard Henschel while she and her husband Moritz were imprisoned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz was an influential lawyer in Berlin when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As government persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany, created by the Nazi government in February 1939 to organize Jewish affairs. The Association was eventually forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association, when Leo Baeck was deported. On June 10, 1943, the Reich Association was shut down and Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

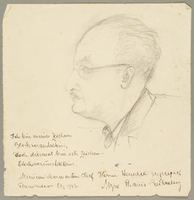

Portrait of a Theresienstadt inmate drawn by another inmate

Object

Portrait drawing of Moritz Henschel by Myra Strauss Rutenberg given to Moritz while he and his wife Hildegard were imprisoned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz was an influential lawyer in Berlin when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As government persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany, created by the Nazi government in February 1939 to organize Jewish affairs. The Association was eventually forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association, when Leo Baeck was deported. On June 10, 1943, the Reich Association was shut down and Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Fighter against the Nazis Medal and box awarded to Jewish Brigade veteran

Object

Fighter Against the Nazis medal and ribbon with box awarded to Shmuel Givol Gotthold. The ribbon was awarded on Holocaust Remembrance Day, May 7, 1967, and the medal several years later. Gotthold was a soldier in the Jewish Brigade, British Army, 2nd Jewish Battalion, Palestine Regiment. In the immediate postwar period he was stationed in the British Zone in Germany where he helped trace missing persons and aided refugees desperate to know whether their family members had survived. The Brigade was established by the British in September 1944. It included more than 5000 Jewish volunteers living in Palestine and was the only independent, national Jewish unit to serve in WWII. The unit served in combat during the final battles for the liberation of Italy. The British dissolved the Brigade in the summer 1946

British Defence Medal 1939-1945 ribbon awarded to Jewish Brigade veteran

Object

British Defence Medal 1939-1945 ribbon awarded to Shmuel Givol Gotthold. Gotthold was a soldier in the Jewish Brigade, British Army, 2nd Jewish Battalion, Palestine Regiment. In the immediate postwar period he was stationed in the British Zone in Germany where he helped trace missing persons and aided refugees desperate to know whether their family members had survived. The Brigade was established by the British in September 1944. It included more than 5000 Jewish volunteers living in Palestine and was the only independent, national Jewish unit to serve in WWII. The unit served in combat during the final battles for the liberation of Italy. The British dissolved the Brigade in the summer 1946

WWI Red Cross medal ribbon awarded to German Jewish woman

Object

Rothe Kreuz [For Merit in the Red Cross] medal ribbon awarded to Hildegard Alexander for her service as a nurse in World War I (1914-1918). See 2003.361.8 for the Rothe Kreuz medal she was also awarded. Her husband, Moritz Henschel, had been decorated for his service in the German Army during the war. Moritz was an influential lawyer in Berlin when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As government persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany, created by the Nazi government in February 1939 to organize Jewish affairs. The Association was eventually forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association, when Leo Baeck was deported. On June 10, 1943, the Reich Association was shut down and Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Book

Object

Book of Goethe's writings taken from the Theresienstadt ghetto library by Moritz Henschel, who was imprisoned there from June 1943 - May 1945. Moritz was an influential lawyer in Berlin when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As the government persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany, created by the Nazi government in February 1939 to organize Jewish affairs. The Association was eventually forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz also became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association, when Leo Baeck was deported. On June 10, 1943, the Reich Association was shut down and Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp in Germany, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Book

Object

Book of Horace's writings taken from the Theresienstadt ghetto library by Moritz Henschel, who was imprisoned there from June 1943 - May 1945. Moritz was an influential lawyer in Berlin when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As the government persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany, created by the Nazi government in February 1939 to organize Jewish affairs. The Association was eventually forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz also became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association, when Leo Baeck was deported. On June 10, 1943, the Reich Association was shut down and Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp in Germany, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Signed print of rabbi saved by German Jewish camp inmate

Object

Portrait print of Rabbi Guttmann saved by Moritz and Hildegard Henschel from their imprisonment in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp between June 1943 and May 1945. The Rabbi and the artist were prominent citizens of Breslau, which was Moritz's home town. Moritz was an influential lawyer in Berlin when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As government persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany, created by the Nazi government in February 1939 to organize Jewish affairs. The Association was eventually forced to assist with deportations. Moritz also became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association, when Leo Baeck was deported. On June 10, 1943, the Reich Association was shut down and Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Watercolor of an oasis with animals made for a German Jewish camp inmate

Object

Humorous drawing of animals in an oasis inscribed to Hildegard Henschel and given to her husband Moritz in April 1944, when they were prisoners in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp. Moritz was an influential lawyer in Berlin when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As government persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany, created by the Nazi government in February 1939 to organize Jewish affairs. The Association was eventually forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association, when Leo Baeck was deported. On June 10, 1943, the Reich Association was shut down and Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Star of David badge imprinted Jude worn by a German Jew

Object

Star of David badge worn by Moritz or Hildegard Henschel who were deported from Berlin to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in June 1943. Moritz was an influential lawyer in Berlin when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As government persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany, created by the Nazi government in February 1939 to organize Jewish affairs. The Association was eventually forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association, when Leo Baeck was deported. On June 10, 1943, the Reich Association was shut down and Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Star of David badge imprinted Jude worn by a German Jew

Object

Star of David badge worn by Moritz or Hildegard Henschel who were deported from Berlin to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in June 1943. Moritz was an influential lawyer in Berlin when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As government persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany, created by the Nazi government in February 1939 to organize Jewish affairs. The Association was eventually forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association, when Leo Baeck was deported. On June 10, 1943, the Reich Association was shut down and Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Star of David badge imprinted Jude worn by a German Jew

Object

Star of David badge worn by Moritz or Hildegard Henschel who were deported from Berlin to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in June 1943. Moritz was an influential lawyer in Berlin when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As government persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany, created by the Nazi government in February 1939 to organize Jewish affairs. The Association was eventually forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association, when Leo Baeck was deported. On June 10, 1943, the Reich Association was shut down and Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Star of David badge imprinted Jude worn by a German Jew

Object

Star of David badge worn by Moritz or Hildegard Henschel who were deported from Berlin to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in June 1943. Moritz was an influential lawyer in Berlin when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As government persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany, created by the Nazi government in February 1939 to organize Jewish affairs. The Association was eventually forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association, when Leo Baeck was deported. On June 10, 1943, the Reich Association was shut down and Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp, 10,000 kronen scrip band owned by inmates

Object

Paper band for stack of Theresienstadt 10,000 kronen notes owned by Hildegard and Moritz Henschel who were interned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German occupied Czechoslovakia from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz and Hildegard were Berlin residents when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany which was forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association. When it was shut down on June 10, 1943, Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 1 krone note owned by former inmates

Object

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 1 [eine] krone note owned by Hildegard and Moritz Henschel who were interned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German occupied Czechoslovakia from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz and Hildegard were Berlin residents when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany which was forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association. When it was shut down on June 10, 1943, Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 2 kronen note owned by former inmates

Object

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 2 [zwei] kronen note owned by Hildegard and Moritz Henschel who were interned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German occupied Czechoslovakia from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz and Hildegard were Berlin residents when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany which was forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association. When it was shut down on June 10, 1943, Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 5 kronen note owned by former inmates

Object

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 5 [funf] kronen note owned by Hildegard and Moritz Henschel who were interned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German occupied Czechoslovakia from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz and Hildegard were Berlin residents when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany which was forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association. When it was shut down on June 10, 1943, Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 10 kronen note owned by former inmates

Object

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 10 [zehn] kronen note owned by Hildegard and Moritz Henschel who were interned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German occupied Czechoslovakia from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz and Hildegard were Berlin residents when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany which was forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association. When it was shut down on June 10, 1943, Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 20 kronen note owned by former inmates

Object

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 20 [zwanzig] kronen note owned by Hildegard and Moritz Henschel who were interned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German occupied Czechoslovakia from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz and Hildegard were Berlin residents when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany which was forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association. When it was shut down on June 10, 1943, Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 50 kronen note owned by former inmates

Object

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 50 [funfzig] kronen note owned by Hildegard and Moritz Henschel who were interned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German occupied Czechoslovakia from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz and Hildegard were Berlin residents when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany which was forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association. When it was shut down on June 10, 1943, Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 100 kronen note owned by former inmates

Object

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 100 [hundert] kronen note owned by Hildegard and Moritz Henschel who were interned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German occupied Czechoslovakia from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz and Hildegard were Berlin residents when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany which was forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association. When it was shut down on June 10, 1943, Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 100 kronen note owned by former inmates

Object

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 100 [hundert] kronen note owned by Hildegard and Moritz Henschel who were interned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German occupied Czechoslovakia from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz and Hildegard were Berlin residents when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany which was forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association. When it was shut down on June 10, 1943, Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp, 5,000 kronen scrip band by former inmates

Object

Paper band for stack of 5,000 kronen Theresienstadt scrip owned by Hildegard and Moritz Henschel who were interned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German occupied Czechoslovakia from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz and Hildegard were Berlin residents when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany which was forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association. When it was shut down on June 10, 1943, Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 1 krone note owned by former inmates

Object

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 1[eine] krone note owned by Hildegard and Moritz Henschel who were interned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German occupied Czechoslovakia from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz and Hildegard were Berlin residents when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany which was forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association. When it was shut down on June 10, 1943, Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 2 kronen note owned by former inmates

Object

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 2 [zwei] kronen note owned by Hildegard and Moritz Henschel who were interned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German occupied Czechoslovakia from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz and Hildegard were Berlin residents when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany which was forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association. When it was shut down on June 10, 1943, Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 10 kronen note owned by former inmates

Object

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 10 [zehn] kronen note owned by Hildegard and Moritz Henschel who were interned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German occupied Czechoslovakia from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz and Hildegard were Berlin residents when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany which was forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association. When it was shut down on June 10, 1943, Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 20 kronen note owned by former inmates

Object

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 20 [zwanzig] kronen note owned by Hildegard and Moritz Henschel who were interned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German occupied Czechoslovakia from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz and Hildegard were Berlin residents when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany which was forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association. When it was shut down on June 10, 1943, Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 5 kronen note owned by former inmates

Object

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 5 [funf] kronen note owned by Hildegard and Moritz Henschel who were interned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German occupied Czechoslovakia from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz and Hildegard were Berlin residents when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany which was forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association. When it was shut down on June 10, 1943, Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 50 kronen note owned by former inmates

Object

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 50 [funfzig] kronen note owned by Hildegard and Moritz Henschel who were interned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German occupied Czechoslovakia from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz and Hildegard were Berlin residents when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany which was forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association. When it was shut down on June 10, 1943, Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp, 5,000 kronen scrip band owned by former inmates

Object

Paper band for stack of 5,000 kronen Theresienstadt scrip owned by Hildegard and Moritz Henschel who were interned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German occupied Czechoslovakia from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz and Hildegard were Berlin residents when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany which was forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association. When it was shut down on June 10, 1943, Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 1 krone note owned by former inmates

Object

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 1[eine] krone note owned by Hildegard and Moritz Henschel who were interned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German occupied Czechoslovakia from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz and Hildegard were Berlin residents when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany which was forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association. When it was shut down on June 10, 1943, Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 2 kronen note owned by former inmates

Object

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 2 [zwei] kronen note owned by Hildegard and Moritz Henschel who were interned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German occupied Czechoslovakia from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz and Hildegard were Berlin residents when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany which was forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association. When it was shut down on June 10, 1943, Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 5 kronen note owned by former inmates

Object

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 5 [funf] kronen note owned by Hildegard and Moritz Henschel who were interned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German occupied Czechoslovakia from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz and Hildegard were Berlin residents when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany which was forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association. When it was shut down on June 10, 1943, Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 10 kronen note owned by former inmates

Object

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 10 [zehn] kronen note owned by Hildegard and Moritz Henschel who were interned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German occupied Czechoslovakia from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz and Hildegard were Berlin residents when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany which was forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association. When it was shut down on June 10, 1943, Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 20 kronen note owned by former inmates

Object

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 20 [zwanzig] kronen note owned by Hildegard and Moritz Henschel who were interned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German occupied Czechoslovakia from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz and Hildegard were Berlin residents when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany which was forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association. When it was shut down on June 10, 1943, Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 50 kronen note owned by former inmates

Object

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 50 [funfzig] kronen note owned by Hildegard and Moritz Henschel who were interned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp in German occupied Czechoslovakia from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz and Hildegard were Berlin residents when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany which was forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association. When it was shut down on June 10, 1943, Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.

Watercolor of flowers given to German Jewish couple in camp

Object

Colorful watercolor of flowers given to Moritz and Hildegard Henschel while interned in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp from June 1943-May 1945. Moritz was an influential lawyer in Berlin when Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. As government persecution of Jews intensified, Moritz and Hildegard sent their daughters Marianne, 15, to Palestine and Lilly, 13, to England in 1939. Moritz was on the board of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany which was forced to assist with deportations. In 1940, Moritz became president of the Berlin Jewish Community. In January 1943, Moritz became president of the Reich Association, which was shut down on June 10, 1943 and Moritz and Hildegard were deported to Theresienstadt. Moritz was elected to the Jewish Council and put in charge of the Freizeitgestaltung, which produced cultural events and materials. On May 9, 1945, the camp was liberated by Soviet forces. Moritz and Hildegard went to Deggendorf displaced persons camp, then emigrated to Palestine in 1946.