Overview

- Brief Narrative

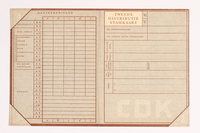

- Sheet of unused ration coupons for foodstuffs used by Gerry van Heel to forge identification documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

- Date

-

issue:

1944 October 01-1944 November 25

- Geography

-

issue:

Netherlands

- Credit Line

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection, Gift of Elise Kann Jaeger

- Markings

- front, right side, upper third, printed, black ink : VOEDINGSMIDDELEN VOOR HOUDERS VAN INLEGVELLEN GC 401 / 11e EN 12e PERIODE 1944 (1 OCTOBER – 25 NOVEMBER) / BONKAART / KC 411-412 [FOOD PRODUCTS FOR HOLDERS OF INSERT SHEETS GC 401 / 11th AND 12th PERIOD 1944 (OCTOBER 1 – NOVEMBER 25) / RECEIPT CARD / KC 411-412]

- Contributor

-

Subject:

Elise Jaeger

Subject: Gerry van Heel

- Biography

-

Elise Kann was born on December 23, 1930, in Dordrecht, Netherlands, to Jacob and Dora Spanjaard Kann. Dora was born on June 8, 1906, in Eindhoven to Isaac and Juliette Spanjaard-Polak. Jacob was born on August 22, 1900, to Jacobus and Anna Daniels Kann, a secular Jewish family in The Hague. Jacobus, born in 1872, was a prominent banker and publisher, an ardent Zionist, and the first Dutch consul in Palestine. Jacob was an electrical engineer for the Philips Company; he had three brothers, Maurits, Eduard, and Johann and a sister Liz in Haifa. Dora and Jacob married in 1928. Elise had three siblings: Otto, born November 26, 1929, Judith, born July 28, 1934, and Jacob, born March 7, 1936. They lived in a large house with servants and a non-Jewish nanny, Nelly Kwikkers-Fortuin. Dora contracted tuberculosis after the birth of her youngest son and was often bedridden. Jacob was active in the Jewish community and the Zionist movement, but they were a secular family and celebrated Christian holidays with their non-Jewish neighbors.

On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. Elise woke up to the sound of airplanes. Life for Elise remained normal. They vacationed that summer in Borne at her maternal grandparents. When they returned that fall, Elise noticed changes: ID cards were issued, food rationed, and radios, bicycles, and valuables were confiscated. The non-Jewish servants left. Elise could not go to the park, movies, or play with non-Jewish friends. Shopping was restricted to certain stores and hours. In summer 1941, Jewish children were no longer allowed to attend public schools; the youngest children attended a Jewish school and Otto went to high school in Rotterdam.

On April 29, 1942, Jews were ordered to wear the Star of David badge. Jacob sat at the dining room table, cutting stars out of yellow cloth, and writing Jude on them. He gave one to each family member and explained that they should wear it with pride. The following week, Jews were required to wear stars bought with their textile rations. Non-Jews were not permitted to work for Jews, but Nelly disobeyed the order, arriving and leaving when it was dark. That summer, the Germans began deporting Jews to concentration camps. Classmates and teachers disappeared. One day, the children came home and found backpacks filled with new clothes; their parents wanted to be prepared if they were deported. A family friend from Dora’s schooldays, Molly van Heel, visited from Eindhoven and told Jacob that the family needed to hide, but he refused. After another visit, he agreed to let Molly take the girls if things got worse. In the fall, Elise arrived at a locked school and was told by the caretaker that the rabbi and cantor had been arrested. Elise waited for her siblings; they covered their stars and rushed home. Otto returned from Rotterdam. One November day, the girls put on as many clothes as possible and removed their stars. Their aunt Joyce took them by train to Eindhoven to live with Molly and her husband Gerry. Nelly hid Jacobus and the family physician, Dr. Eppo Meursing, arranged a hiding place for Otto, Jacob, and Dora in a small house on their property. That night, the Germans vandalized the main house. Dr. Meursing sent a carriage for Dora and Jacob and admitted them into the hospital, Dora for tuberculosis, and Jacob, in a fake cast, for a broken leg. Dora’s condition had worsened and she remained in the hospital until it became too dangerous. Dr. Meursing found a nurse, Mrs. Struys, to stay with her in hiding. Six year old Jacobus was sent to Badhoevendorp to live with Noor and Hilde van Andel and their four children. Elise’s father changed his name to Hank and hid with Otto in the home of the nurse’s sister.

Molly and Gerry changed the girls’ name to Kan, a Christian name. They told people that their house in Rotterdam had been bombed, their mother was hospitalized, and their father worked in Germany. They lived in two attic bedrooms with a secret room. The girls went to a Christian school where the schoolmaster was aware of their situation. Nelly brought clothes and relayed news between family members. A German security officer moved into the house, but Molly only allowed him to sleep there during the week.

In November 1943, Otto, now hiding with a different family, was out when German police conducted a search of the house. When questioned, the landlady disclosed that Otto was Jewish and that his father was in hiding also. Otto and Jacob were arrested and placed on a train for Westerbork transit camp. They stood by the door and when the train slowed, Jacob opened the door, and they jumped and ran. Jacob was shot in the shoulder, but he gave Otto the address of a new hiding place and told him to go there. Otto found refuge, but Jacob was caught and, in January 1944, deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp. Dora died in Huizen on June 4, 1944.

The Allies landed in Normandy on June 1944 and soon were advancing near Netherlands. On September 18, Eindhoven was liberated by the US Army, 101st Airborne Division. The next day, Molly and the girls used their ration coupons to buy food and make sandwiches for the soldiers. That night, German planes bombed the city.

The rest of Holland was still occupied and the soldiers left. Elise told her friends that she was Jewish and they accepted her. She joined the Girl Scouts, assisted refugees, and returned to school. When the war ended in early May 1945, Molly, who was working for the Red Cross, arranged to have Elise and Judith taken to their maternal grandmother, Juliette. She had been in hiding but now returned to her home in Hengelo; her husband, Isaac, had died in hiding. Their brother, Jacob, was in the northern region which was liberated late and suffered horrendous food shortages because of the German blockade. Mr. van Andel brought Jacob to his grandmother’s on a bike with no wheels, just rag wrappings. Otto also joined them there. They learned that their father had been killed on arrival in Auschwitz. Their paternal grandfathers had been deported in spring 1943 to Theresienstadt concentration camp where Jacob died on October 7, 1944, and Anna on April 28, 1945. Two paternal uncles, Maurits and his wife and Johann were killed in the camps.

Elise married Jacques Jaeger and in 1955, the family emigrated to the United States. The couple had 4 children. Her sister Judith moved to Israel in 1960 where she married Habib Bar-Kochba and had five children.

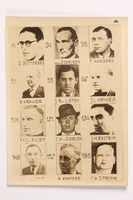

Gerry (Gerard Louis) van Heel, his wife Molly (Marie Gertrude), and his brother-in-law Johann, were Dutch rescuers in Eindhoven, Netherlands, during World War II. Molly was a social worker and Gerry was an engineer for the Philips company. They lived in a five bedroom duplex in a development built for Phillips employees. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands, and on May 14, the Dutch Army surrendered. Deportations of Dutch Jews began in the summer of 1942. Dutch citizens and resistance groups organized rescue efforts. Gerry and Molly were fluent in English, French, and German. Jews, wounded English pilots, and Dutch officers frequently took refuge at the van Heel house; three short rings of the door bell allowed entry. Gerry and Johann became expert at creating false identification cards and other documents.

Molly had been urging her close Jewish friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding with their four children. Dora had been born in Eindhoven and she and Molly had been friends since childhood. In the fall of 1942, 12 year old Elise and 8 year old Judith Kann, came from Dordrecht to live with Molly and Gerry. The couple changed the girls’ last name to Kan, a Christian name, and enrolled them in a Christian school. They told people that the girls were from Rotterdam where their home had been bombed and their mother hospitalized, and that their father was working in Germany. Elise and Judith lived in two attic bedrooms with a secret room under the eaves. Gerry instructed the girls in what to do if there was a problem: to hide their belongings in the bedclothes and flip the mattress so that the room seemed uninhabited, then to hide in the secret room.

With so many people now living under one roof, they began using more than the allotted amount of gas and electricity. Each Sunday, Gerry disconnected the gas meter and attached it to the vacuum cleaner hose to suction the meter back to an appropriate number. However, since the vacuum cleaner used too much electricity, Gerry made a tool to open the electric meter to change the numbers. The Germans checked the numbers on Monday mornings, and the household was never over their allotment. Gerry bought food on the black market since food was strictly rationed and they needed to hide the extra purchases. Radios were prohibited but they hid one, along with other valuables, in a false ceiling and they often listened to the BBC. Secret correspondence went through the neighbors; specially marked envelopes were meant for Molly and Gerry. The couple avoided housing German soldiers and believed Gerry’s boss intervened and kept them away. Every so often, a soldier came to the door, but Molly told them there were no rooms available.

Gerry stole legal ID cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge cards. Serial numbers had to be changed; Gerry erased easy to change numbers, such as 0, 8, and 6. If the erasure damaged the paper, he made paper and attached it to the document with an iron. Photos were attached using a water soluble glue. Gerry made his own ink to match the official ink. He worked in the maid’s room and no one was allowed entry. Johann was part of a resistance group. He stole official German stamps and made ID cards. Johann worked and hid his materials in the secret attic room until he was turned in to the authorities, imprisoned, and executed. Afterwards, Molly did not have the strength to say no to a German security officer who asked for a room in the house. She told him that he could sleep there, but he was not allowed to stay during the day or over the weekends. He did not suspect their underground activities.

In September 1944, there was a country wide railroad strike and allied forces were advancing into the Netherlands. Many Germans retreated on foot, including the security officer boarding with them. On September 17, English and American forces bombed the airport and transportation depots and dropped grenades. One landed in Molly and Gerry’s bed but did not explode; Gerry threw it out the window and it detonated later that day. English and American paratroopers landed north of Eindhoven and Gerry left to meet the soldiers and to assist as a translator. On September 18, Eindhoven was liberated by the United States 101st Airborne Division. That night, German planes bombed the city. Gerry, Molly, the two girls, and a US soldier hid in the basement. The house next door caught fire; Gerry, Molly, Elise, and Judith escaped. The soldier and neighbors died.

The war ended on May 5, 1945. Molly worked for the Red Cross and in late May arranged for a convoy to transport Elise and Judith to their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, in Hengelo (Overijssel, Netherlands) where they were reunited with their two brothers. The girl’s mother had died of tuberculosis and their father had been deported and killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp. Molly and Gerry stayed in touch with the girls after the war. Molly died in the 1990s; Gerald passed away in 1999-2000.

Physical Details

- Language

- Dutch

- Classification

-

Exchange Media

- Category

-

Coupons

- Object Type

-

Ration cards (lcsh)

- Genre/Form

- Documents

- Physical Description

- Unused, rectangular, tan, card with multiple colorful, gridded and labeled sections to be cut-out when used. The gridlines and Dutch labels are printed in black ink and indicate what amount of a particular foodstuff could be received in exchange for the coupon. The period of use and card number are indicated in a long, narrow section near the top of the right side.

- Dimensions

- overall: Height: 6.750 inches (17.145 cm) | Width: 14.750 inches (37.465 cm)

- Materials

- overall : paper, ink

Rights & Restrictions

- Conditions on Access

- No restrictions on access

- Conditions on Use

- No restrictions on use

Keywords & Subjects

Administrative Notes

- Legal Status

- Permanent Collection

- Provenance

- The ration coupon sheet was donated to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in 2017 by Elise Jaeger.

- Record last modified:

- 2024-04-29 07:53:20

- This page:

- https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn564705

Download & Licensing

In-Person Research

- By Appointment

- Request 21 Days in Advance of Visit

- Plan a Research Visit

- Request to See This Object

Contact Us

Also in Gerard van Heel collection

The collection consists of artifacts and documents relating to the experiences of Gerard (Jerry) and Molly van Heel, Dutch resistance members who hid two young sisters, Elise and Judith Kann, in Eindhoven, Netherlands, during the Holocaust.

Date: 1942-1944

Circular, German postal hand stamp used by Gerry van Heel to forge identification documents

Object

Circular, metal hand stamp on a block mount used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Circular, Amsterdam hand stamp used by Gerry van Heel to forge identification documents

Object

Circular, rubber hand stamp with a wooden handle used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Rectangular, Arnheim hand stamp used by Gerry van Heel to forge identification documents

Object

Rectangular, rubber hand stamp with a wooden handle and the word Arnheim used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Oval-shaped, Dutch hand stamp used by Gerry van Heel to forge identification documents

Object

Oval-shaped, rubber hand stamp with a wooden handle used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Circular, Hague hand stamp used by Gerry van Heel to forge identification documents

Object

Circular, rubber hand stamp with Gemeente Gravenhage [municipality of Hague] used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Large, dark blue ink pad used by Gerry van Heel to forge identification documents

Object

Stamp ink pad in a metal tin used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Small, ink roller used by Gerry van Heel to forge identification documents

Object

Small ink roller used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

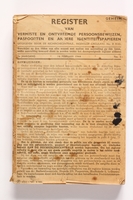

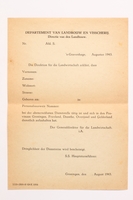

Account book used by Gerry van Heel to forge identification documents

Object

Register or account book used used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Accordion folder used by Gerry van Heel to forge identification documents

Object

Accordion folder used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

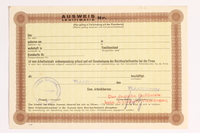

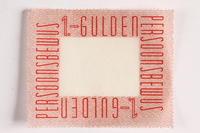

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents

Object

Blank ID card used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

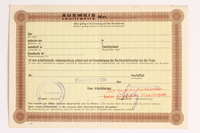

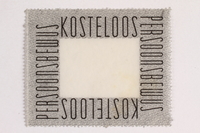

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents

Object

Blank ID card used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

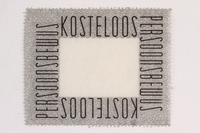

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents

Object

Blank ID card used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents

Object

Blank ID card used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents

Object

Blank ID card used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents

Object

Blank ID card used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

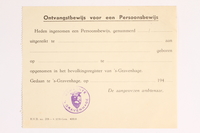

Blank certificate used by Gerry van Heel to forge identity documents

Object

Blank certificate used by Gerry van Heel to forge identification documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents

Object

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents

Object

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents

Object

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents

Object

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

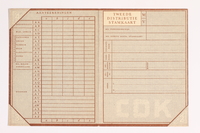

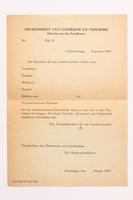

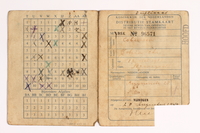

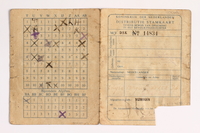

Blank distribution card used by Gerry van Heel to forge identity documents

Object

Blank distribution card used by Gerry van Heel to forge identification documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank distribution card used by Gerry van Heel to forge identity documents

Object

Blank distribution card used by Gerry van Heel to forge identification documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

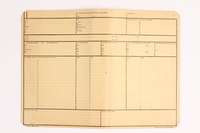

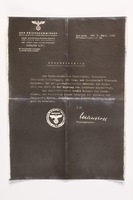

Blank form used by Gerry van Heel to forge identity documents

Object

Blank form used by Gerry van Heel to forge identification documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank form used by Gerry van Heel to forge identity documents

Object

Blank form used by Gerry van Heel to forge identification documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank form and envelope used by Gerry van Heel to forge identity documents

Object

Blank form and envelope used by Gerry van Heel to forge identification documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

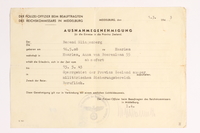

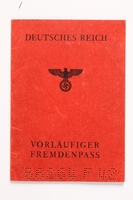

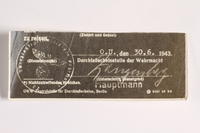

Safe conduct pass for Berend Slingenberg created by Gerry van Heel, a document forger

Object

Completed safe conduct pass for Berend Slingenberg by Gerry van Heel, who forged documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Safe conduct pass for Berend Slingenberg created by Gerry van Heel, a document forger

Object

Completed safe conduct pass for Berend Slingenberg by Gerry van Heel, who forged documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

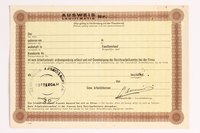

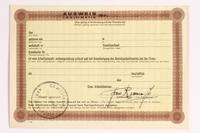

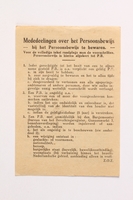

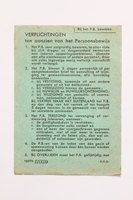

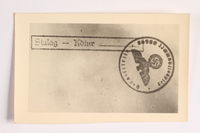

Blank safe conduct pass used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents

Object

Blank safe conduct pass used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank safe conduct pass used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents

Object

Blank safe conduct pass used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank safe conduct pass used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents

Object

Blank safe conduct pass used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank safe conduct pass used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents

Object

Blank safe conduct pass used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank safe conduct pass used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents

Object

Blank safe conduct pass used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank safe conduct pass used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents

Object

Blank safe conduct pass used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank safe conduct pass used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents

Object

Blank safe conduct pass used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank safe conduct pass used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents

Object

Blank safe conduct pass used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank safe conduct pass used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents

Object

Blank safe conduct pass used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank safe conduct pass used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents

Object

Blank safe conduct pass used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank safe conduct pass used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents

Object

Blank safe conduct pass used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Safe conduct pass for H. A. Touw created by Gerry van Heel, a document forger

Object

Completed safe conduct pass for someone named H. A. Touw by Gerry van Heel, who forged documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank safe conduct pass used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents

Object

Blank safe conduct pass used by Gerry van Heel to forge documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Identification card for Martina Geertruda van Wanrooj created by Gerry van Heel, a document forger

Object

Completed identification card created for Martina Geertruda van Wanrooj by Gerry van Heel, who forged identification documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge identity documents

Object

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge identification documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge identity documents

Object

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge identification documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge identity documents

Object

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge identification documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge identity documents

Object

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge identification documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge identity documents

Object

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge identification documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge identity documents

Object

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge identification documents for the Dutch resistance and for Jewish people living in hiding in Eindhoven, Holland. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By summer 1942, the Germans were deporting Jews to concentration camps. Gerry and his wife, Molly, aided resistance efforts by hiding wounded English pilots, Dutch Army officers, and Jews. In the fall of 1942, Molly urged her friends, Dora and Jacob Kann, to go into hiding. Molly and Gerald hid Dora's young daughters, 12-year-old Elise and 8-year-old Judith. Their brothers, 14-year-old Otto and 5-year-old Jacob, were hidden in different homes. Gerry stole legal identification cards and official administrative stamps and used them to forge ID cards and documents. He replaced the photos and personal information and made his own ink and paper. On September 18, 1944, Eindhoven was liberated by the US 101st Airborne Division. Elise and Judith's mother, Dora, had died of tuberculosis and their father, Jacob, was killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in German-occupied Poland. After the war ended in May 1945, Molly sent Elise and Judith to live with their maternal grandmother, Juliette Spanjaard-Polak, where they were reunited with their brothers.

Blank identification card used by Gerry van Heel to forge identity documents

Object