Overview

- Brief Narrative

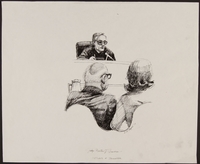

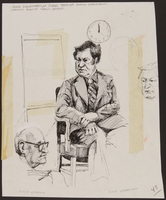

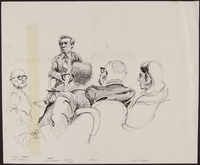

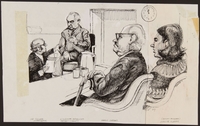

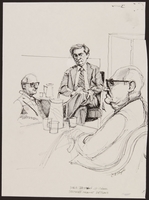

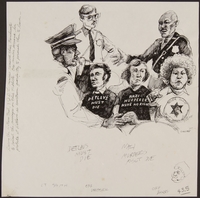

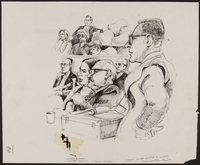

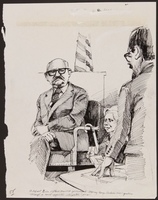

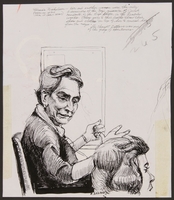

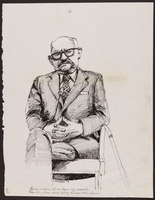

- Two sided drawing of Raul Hilberg, government's opening witness, created by Charles (Hap) Hazard at the deportation trial of George Theodorovich in 1985 in Baltimore, Maryland. In August 1983, the OSI brought charges against Theodorovich for killing unarmed Jews. Theodorovich was stripped of his US citizenship in 1984. His disappeared from his home and was the subject of a federal manhunt. After his capture in Philadelphia, he was tried for moral turpitude and failure to disclose wartine activities. In 1987, Theodorovich was found guilty and ordered deported in 1988 because of his involvement in the murder of Jews in Lvov, Poland (Lviv, Ukraine) during the Holocaust. The US wished to deport him to the Soviet Union, but a deportee has the right to choose the country to which his is deported, although that country must agree to accept him. In December 1988, Theodorovich deported himself to Paraguay. At the time, he was the 26th person to receive a deportation order from the US government as a result of investigations and prosecutions by the OSI, Office of Special Investigations, US Department of Justice. The OSI pursued prosecutions in order to deny Nazis and war criminals a safe haven in the US. Hilberg opened the proceedings by describing how Ukrainian police cooperated with the Germans in the round-up of Jews in Lvov and how a community of 130,000 was reduced to 1000. Hilberg was a world renowned scholar, who published the first comprehensive study of the Holocaust and initiated the academic study of the Holocaust. Hazard was assigned to cover the trial and create courtroom drawings for the Baltimore Sun.

- Artwork Title

- Raul Hilberg Testifies at Deportation Trial of Accused War Criminal

- Series Title

- George Theodorovich Trial, Baltimore, Maryland, 1985

- Date

-

creation:

1985

- Geography

-

creation:

Baltimore (Md.)

- Credit Line

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection, Gift of Charles R. Hazard and The Baltimore Sun

- Signature

- front, lower left, black ink : Charles R. Hazard

- Contributor

-

Artist:

Charles R. Hazard

Subject: George Theodorovich

Subject: Raul Hilberg

- Biography

-

Charles Rodger Hazard (Hap, 1947-2018) was born to Charles O. and Stella Dernoga Hazard in Baltimore, Maryland. His father served in the United States (US) Army during World War II (1939-1945). He worked as a topographical engineer for British Intelligence, mapping the French coastline in preparation for the D-Day landings, and was later transferred to the Pacific theater. After the war, he worked in the advertising art department for the Baltimore Sun. Charles’ mother, Stella, worked at the Sun during the war as the first female staff artist. Charles’ sister, Carla Tomaszewski, also worked as a professional artist.

After graduating from high school in 1965, Charles enrolled at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA). However, due to the conflict in Vietnam, he enlisted in the US Army and was assigned to military intelligence because of his gift for languages. In 1968, prior to his deployment overseas, Charles married Miriam Deborah Wolfe. Upon his return in 1969, he began his work as a political illustrator for the Baltimore Sun newspapers. During a career that spanned more than 30 years, Charles created illustrations and court room drawings of memorable historical and political events for the newspaper. Charles and Miriam had four children. After retiring from the Sun, Charles worked as an editorial artist for the Washington Times newspaper. The National Park Service commissioned Charles to provide illustrations for numerous national landmarks. He came out of retirement to create fourteen illustrations of scenes from the Battle of Gettysburg for background murals on display at the Museum and Visitor Center at Gettysburg National Military Park, which opened in 2008.

Jurij Teodorowytsch (later George Theodorovich) was born in 1923 in Szuparka, Poland, now part of Ukraine. He is presumed to have lived in Lvov from 1936-1944, joining the police force in May 1942. In 1942, he was a Ukrainian policeman in Lvov, during the German occupation of Poland, following its invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. As an armed, uniformed policeman, he patrolled the streets, enforcing the German authorities anti-Jewish policies. According to wage records, he also served as a guard at a forced labor camp in 1944. Lvov was liberated by the Polish Home Guard and the Red Army in July 1944. The war ended in May 1945.

Theodorovich came to the US in 1948 as a postwar refugee, stating that he had been a student during World War II. He settled in Troy, NY and worked as a meat cutter. He became a naturalized citizen in 1960, repeating his statement of having been a student during the war. The US Department of Justice, Office of Special Investigations (OSI) interviewed Theodorovich in 1982 about his activities in Lvov in 1942. They had police reports, obtained from Soviet archives, that Theodorovich had signed as a Ukrainian policeman, accounting for the number of bullets used to kill individual Jews. Theodorovich admitted that he was a policeman and that the handwriting looked like his, but denied the charges, stating: ‘It says I killed six Jews and left their bodies there. It's my handwriting, it looks like mine, but I never did that.” In August 1983, the OSI brought charges against him for the killing of unarmed Jews. He was also charged with rounding up Jews for concentration and forced labor camps, and confiscating their personal property. The same month, Theodorovich disappeared from his home in Troy, NY, and became the object of a federal manhunt. In January 1984, his citizenship was revoked by a federal judge Charles Richey, for withholding information about his background and lying about not taking part in atrocities from 1942-44. This was done at the request of the OSI after Theodorovich failed to appear in court as ordered to answer questions about his wartime activities. It was thought he was out of the county. But in April 1984, he was arrested by an immigration agent at his sister’s home in Philadelphia.

The US Immigration and Naturalization Service stripped Theodorovich of his US citizenship. OSI then initiated deportation proceedings against him, and Theodorovich stood trial in federal court in a non-jury trial in Baltimore in 1985. He was provided a translator by the court. The OSI was represented by attorney Bruce Solow. Theodorovich was charged with crimes of moral turpitude and for not disclosing his wartime activities when he entered the country in 1948. During the trial, the OSI submitted as evidence the papers that Theodorovich had signed in 1942 as a Ukrainian policeman, accounting for the use of the bullets and the killings of Jews during an action against Jews in Lvov. Theodorovich reported firing on two occasions, killing two Jews each time. The government’s opening witness at the trial was Raul Hilberg, a leading historian of the Holocaust. Hilberg testified that the Nazi-organized Ukrainian police were instrumental in the roundup of Jews in Lvov in 1941 and 1942, reducing a population of 130,000 Jews to about 1000, who survived by living in hiding. The OSI also presented multiple Jewish survivors of the Lvov ghetto to give testimony about the brutal actions of the Ukrainian police, although none testified about Theodorovich's role. Theodorovich first denied having been a policemen or witnessing Jewish roundups or killings, then admitted that he was in the Ukrainian police and did write the reports.

In 1987, Judge John F. Gossart, an immigration judge found Theodorovich guilty not of assisting in the persecution of Jews, but of being a persecutor. He was also found guilty of falsifying his record, and was deportable on all charges. Theodorovich asked to be deported to Argentina. The OSI requested that he be deported to the Soviet Union, his native land. The US had no extradition treaty with the USSR, but the Soviet government indicated that it would accept and try Theodorovich. Under US law, a deportee has the right to choose the country to which he will be deported, as long as that country will accept him or her. They are permanently banned from entering the US and placed on a watch list.

In December 1988, Theodorovich deported himself to Paraguay. He had obtained a safe-conduct pass from the Paraguayan consul general in New York City on December 6, signed by Felix Aguero. Another former Ukrainian policeman, Sergei Kowalchuk, found guilt of similar charges around this time, and also facing deportation to the Soviet Union, had previously gone to Paraguay. A third Ukrainian accused of being a Nazi war criminal, Feodor Fedorenko, a guard at Treblinka, had been deported to the Soviet Union in December 1984, and later executed.

Raul Hilberg was born on June 2, 1926, in Vienna, Austria, the only child of Jewish parents. His father Michael fought and was wounded in the First World War (1914-1918). In Vienna, he had a business selling household goods to people on installment plans. His parents attended synagogue occasionally. Raul was never religious, but he did attend a Zionist school. In March 1938, Nazi Germany annexed Austria and soon passed legislation to strip Jews of their rights as citizens. The family was ordered out of their apartment by gunpoint. His father was arrested during Kristallnacht, September 9-10 1938, but was soon released because he was a World War I veteran.

The family left Austria and after stopovers in France and Cuba, reached Brooklyn, NY, on September 1, 1939. Michael worked in a factory and Hilberg attended Lincoln High School. He enrolled in Brooklyn College until enlisting in the Army in 1944. He was deployed to Germany in 1945 with the 45th infantry division. He served with an Oklahoma division that liberated Dachau, but was not with the unit at the time. He was with the first troops that entered Munich. He was later assigned to the Army documentation division, which needed staff fluent in German. The war ended in May 1945. Nearly all the members of Hilberg's family on both his mother's and father's side were murdered during the Holocaust. Postwar, Hilberg assisted in the search for German documents to aid the prosecution at the war crimes trials. His unit was housed in the Nazi Party’s former offices in Munich. Crates containing Hitler’s personal library were stored there and Hilberg was fascinated by the contents. After his discharge, he returned to Brooklyn College and changed his major from chemistry to history and political science, graduating in 1948. He then focused on political science and international law and completed a master’s in public law in 1950 at Columbia University. He taught at Hunter College and then obtained a federal job in the War Documentation Project in Alexandria, Va., cataloging documents released from German archives, copying by hand material necessary to his own research. He received his doctorate from Columbia in 1955. His dissertation was on the Holocaust, which was not then a topic of academic study. His adviser, Franz Neumann, warned him that the subject would be detrimental to his career.

In 1956, he took a position at the University of Vermont. In 1961, his book, “The Destruction of the European Jews” was published. It was the first comprehensive study of the Holocaust and established the field of Holocaust studies. It was a methodical, evidentiary work detailing the systematic, bureaucratic process that led to the mass murder of Jews as a matter of routine. Rejected by five publishers, it was accepted by the small Quadrangle Company after a patron, Frank Petschek, a wealthy businesman who had fled German occupied Czechoslovakia in fall 1938, agreed to subsidize the print run and purchase 1300 copies for libraries. In 1974, Hilberg offered the first college-level course on the Holocaust. He expanded his original work to three volumes and published five more books on the topic, as well as a memoir. He retired from the University of Vermont in 1991, after thirty-five years.

Hilberg was dedicated to expanding the public understanding of the Holocaust. He was a key figure in the development and establishment of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, serving as an original member of the President’s Commission on the Holocaust (1978–79) and on the United States Holocaust Memorial Council from 1980 through 1988. In 2006, he received the Knight Commander’s Order of Merit in Germany, the highest award given to non-German citizens. Hilberg married Christine Hemenway in the 1950s. They had two children, and eventually divorced. In 1980, he married Gwendolyn Montgomery. Hilberg, 81, died of lung cancer in Williston, Vt., on August 4, 2007.

Physical Details

- Language

- English

- Classification

-

Art

- Category

-

Drawings

- Object Type

-

Courtroom art (lcsh)

- Physical Description

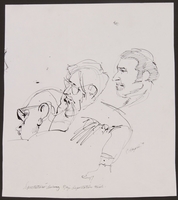

- Two-sided black ink drawing on paper depicting Hilberg, an older man with dark glasses, raised eyebrows and slicked back hair, wearing a black suit and tie, seated at a table with his hands folded on top of papers, with a cup and a small microphone. Behind him is a goateed man in a light colored suit and striped tie, with his left fist on his chin. To his right is are 2 men in suits with somber expressions. The younger man with glasses appears to be speaking into the microphone. At the top and bottom are inscriptions in black ink. There are captions below the images. On the reverse is a portrait sketch of a man, perhaps Hilberg, with slicked back hair and raised eyebrows, wearing glasses, a suit and tie, and holding a piece of paper in his right hand, with a pencilled note.

- Dimensions

- overall: Height: 14.625 inches (37.148 cm) | Width: 11.500 inches (29.21 cm)

- Materials

- overall : paper, ink

- Inscription

- front, top right, handwritten, black ink : Government witness, Raul Hilberg, testifies at the deportation / hearing, in Baltimore Federal Court, of George Theodorovitcz, / accused of being a former PolicE officer who participated in wartime / atrocities against Ukrainian Jews. / COURTROOM SKETCH BY SUNPAPERS ARTIST, CHARLES / R. HAZARD

front, bottom left corner, handwritten, black ink : RAUL / Dr. Hilberg

front, bottom center, handwritten, black ink : DR. RAUL HILBERG / (GOVT. WITNESS) ANDRIJ W. / CHORNODOLSKY / (COURT INTERPRETOR) GEORGE / THEODOROVITCZ / (FORMER UKRAINAN / POLICE OFFICER) JOHN ROGERS CARROLL / (DEFENSE ATTORNEY) / UNIVERSITY OF VERMONT - Author of Destruction of Eastern European Jews - U.S. Government Expert -

back, center left, below portrait, handwritten, black ink : Not a / good / likeness

Rights & Restrictions

- Conditions on Access

- No restrictions on access

- Conditions on Use

- No restrictions on use

Keywords & Subjects

- Topical Term

- Courtroom artists--United States--Baltimore--Biography. Holocaust, Jewish (1939-1945)--Ukraine. War criminals--Government policy--United States--Biography. War criminals--United States--History--20th century. World War, 1939-1945--Collaborationists--Ukraine.

- Personal Name

- Hilberg, Raul, 1926-2007--Pictorial works.

Administrative Notes

- Legal Status

- Permanent Collection

- Provenance

- The drawing was donated to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in 1989 by Charles R. Hazard and the Baltimore Sun newspaper.

- Funding Note

- The cataloging of this artifact has been supported by a grant from the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany.

- Record last modified:

- 2024-04-29 07:55:55

- This page:

- https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn1169

Download & Licensing

In-Person Research

- By Appointment

- Request 21 Days in Advance of Visit

- Plan a Research Visit

- Request to See This Object

Contact Us

Also in Charles R. Hazard and The Baltimore Sun collection

The collection consists of fifteen courtroom sketches created by Charles R. Hazard for the Baltimore Sun newspaper during the postwar deportation trials of Karlis Detlavs and George Theodorovich in Baltimore, Maryland, for withholding information about their involvement with war crimes in Eastern Europe during World War II.

Date: 1977-1985

Drawing of judge speaking to defendant, an accused Latvian war criminal

Object

Courtroom drawing created by Charles (Hap) Hazard while on assignment for the Baltimore Sun newspaper during the November 1977 deportation trial of Karlis Detlavs held in Baltimore, Maryland. It depicts Detlavs, his daughter, and the Honorable Martin J. Travers, a federal immigration judge for the United States Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS). Detlavs was accused of withholding information on his petition for permanent residency by denying involvement in Nazi war crimes during World War II (1939-1945). He was accused of executing Jews in the Riga ghetto and selecting Jews for execution in the Dwinsk ghetto in 1943, while a member of the Latvian Auxiliary Security Police during the German occupation. In 1950, Detlavs emigrated from Munich, Germany, as displaced refugee, with his pregnant wife and young daughter. The family immigrated to the US and settled in Baltimore. In October 1976, the Office of Special Investigations, US Department of Justice, accused Detlavs of war crimes and the INS filed a deportation action. After four days of hearings, Judge Travers announced a continuance so the prosecution could obtain more evidence from Soviet sources. In June 1978, while Judge Travers was on assignment in the US Virgin Islands, part of his circuit at the time, he was stabbed to death. New hearings in the Detlavs trial were held in November 1978 and January 1979. While Detlavs admitted being a member of the Latvian Legion, he denied committing any crimes. Judge Emil Bobek denounced Detlavs for his lack of credibility, but ruled that the identification of Detlavs as a perpetrator was not reliable and a lie was not enough to warrant deportation. The ruling was upheld on appeal.

Drawing of judge and US attorney at trial of accused Latvian war criminal

Object

Courtroom drawing created by Charles (Hap) Hazard while on assignment for the Baltimore Sun newspaper during the November 1977 deportation trial of Karlis Detlavs held in Baltimore, Maryland. It depicts the Honorable Martin J. Travers, a federal immigration judge for the United States Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), and three federal attorneys for the prosecution, including lead INS attorney James Grable. Detlavs was accused of withholding information on his petition for permanent residency by denying involvement in Nazi war crimes during World War II (1939-1945). He was accused of executing Jews in the Riga ghetto and selecting Jews for execution in the Dwinsk ghetto in 1943, while a member of the Latvian Auxiliary Security Police during the German occupation. In 1950, Detlavs emigrated from Munich, Germany, as displaced refugee, with his pregnant wife and young daughter. The family immigrated to the US and settled in Baltimore. In October 1976, the Office of Special Investigations, US Department of Justice, accused Detlavs of war crimes and the INS filed a deportation action. After four days of hearings, Judge Travers announced a continuance so the prosecution could obtain more evidence from Soviet sources. In June 1978, while Judge Travers was on assignment in the US Virgin Islands, part of his circuit at the time, he was stabbed to death. New hearings in the Detlavs trial were held in November 1978 and January 1979. While Detlavs admitted being a member of the Latvian Legion, he denied committing any crimes. Judge Emil Bobek denounced Detlavs for his lack of credibility, but ruled that the identification of Detlavs as a perpetrator was not reliable and a lie was not enough to warrant deportation. The ruling was upheld on appeal.

Drawing of a Holocaust survivor tesifying at trial of accused Latvian war criminal

Object

Courtroom drawing created by Charles (Hap) Hazard while on assignment for the Baltimore Sun newspaper during the November 1977 deportation trial of Karlis Detlavs held in Baltimore, Maryland. It depicts It depicts Jacob Wagenheim, a Holocaust survivor and witness, testifying about Detlavs involvement, and the Yiddish interpreter, Moses Aberbach. Detlavs was accused of withholding information on his petition for permanent residency by denying involvement in Nazi war crimes during World War II (1939-1945). He was accused of executing Jews in the Riga ghetto and selecting Jews for execution in the Dwinsk ghetto in 1943, while a member of the Latvian Auxiliary Security Police during the German occupation. In 1950, Detlavs emigrated from Munich, Germany, as displaced refugee, with his pregnant wife and young daughter. The family immigrated to the United States and settled in Baltimore. In October 1976, the Office of Special Investigations, US Department of Justice, accused Detlavs of war crimes and the US Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) filed a deportation action. After four days of hearings, the Honorable Martin J. Travers, the federal immigration judge for the case, announced a continuance so the prosecution could obtain more evidence from Soviet Sources. In June 1978, while Judge Travers was on assignment in the US Virgin Islands, part of his circuit at the time, he was stabbed to death. New hearings in the Detlavs trial were held in November 1978 and January 1979. While Detlavs admitted being a member of the Latvian Legion, he denied committing any crimes. Judge Emil Bobek denounced Detlavs for his lack of credibility, but ruled that the identification of Detlavs as a perpetrator was not reliable and a lie was not enough to warrant deportation. The ruling was upheld on appeal.

Drawing of eyewitness and interpreter at trial of accused Latvian war criminal

Object

Courtroom drawing created by Charles (Hap) Hazard while on assignment for the Baltimore Sun newspaper during the November 1977 deportation trial of Karlis Detlavs held in Baltimore, Maryland. It depicts It depicts Jacob Wagenheim, a Holocaust survivor and witness, testifying about Detlavs involvement, and the Yiddish interpreter, Moses Aberbach. Detlavs was accused of withholding information on his petition for permanent residency by denying involvement in Nazi war crimes during World War II (1939-1945). He was accused of executing Jews in the Riga ghetto and selecting Jews for execution in the Dwinsk ghetto in 1943, while a member of the Latvian Auxiliary Security Police during the German occupation. In 1950, Detlavs emigrated from Munich, Germany, as displaced refugee, with his pregnant wife and young daughter. The family immigrated to the United States and settled in Baltimore. In October 1976, the Office of Special Investigations, US Department of Justice, accused Detlavs of war crimes and the US Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) filed a deportation action. After four days of hearings, the Honorable Martin J. Travers, the federal immigration judge for the case, announced a continuance so the prosecution could obtain more evidence from Soviet sources. In June 1978, while Judge Travers was on assignment in the US Virgin Islands, part of his circuit at the time, he was stabbed to death. New hearings in the Detlavs trial were held in November 1978 and January 1979. While Detlavs admitted being a member of the Latvian Legion, he denied committing any crimes. Judge Emil Bobek denounced Detlavs for his lack of credibility, but ruled that the identification of Detlavs as a perpetrator was not reliable and a lie was not enough to warrant deportation. The ruling was upheld on appeal.

Drawing of accuser and accused at trial of suspected Latvian war criminal

Object

Courtroom drawing created by Charles (Hap) Hazard while on assignment for the Baltimore Sun newspaper during the November 1977 deportation trial of Karlis Detlavs held in Baltimore, Maryland. It depicts Detlavs, his daughter, and their attorney, looking at Holocaust survivor and prosecution witness, Boris Tsesvan, and Yiddish interpreter, Moses Aberbach. Tsesvan identified Detlavs as one of the uniformed guards who beat and took away another Jewish forced laborer from the Hotel Roma in Riga, Latvia, in June 1943. Detlavs was accused of withholding information on his petition for permanent residency by denying involvement in Nazi war crimes during World War II (1939-1945). He was accused of executing Jews in the Riga ghetto and selecting Jews for execution in the Dwinsk ghetto in 1943, while a member of the Latvian Auxiliary Security Police during the German occupation. In 1950, Detlavs emigrated from Munich, Germany, as displaced refugee, with his pregnant wife and young daughter. The family immigrated to the United States and settled in Baltimore. In October 1976, the Office of Special Investigations, US Department of Justice, accused Detlavs of war crimes and the US Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) filed a deportation action. After four days of hearings, the Honorable Martin J. Travers, the federal immigration judge for the case, announced a continuance so the prosecution could obtain more evidence from Soviet sources. In June 1978, while Judge Travers was on assignment in the US Virgin Islands, part of his circuit at the time, he was stabbed to death. New hearings in the Detlavs trial were held in November 1978 and January 1979. While Detlavs admitted being a member of the Latvian Legion, he denied committing any crimes. Judge Emil Bobek denounced Detlavs for his lack of credibility, but ruled that the identification of Detlavs as a perpetrator was not reliable and a lie was not enough to warrant deportation. The ruling was upheld on appeal.

Drawing of eyewitness identifying defendant at trial of Latvian war criminal

Object

Courtroom drawing created by Charles (Hap) Hazard while on assignment for the Baltimore Sun newspaper during the November 1977 deportation trial of Karlis Detlavs held in Baltimore, Maryland. It depicts Detlavs and his daughter looking at the Yiddish interpreter, Mr. Smolar, and a Holocaust survivor and witness for the prosecution. Detlavs was accused of withholding information on his petition for permanent residency by denying involvement in Nazi war crimes during World War II (1939-1945). He was accused of executing Jews in the Riga ghetto and selecting Jews for execution in the Dwinsk ghetto in 1943, while a member of the Latvian Auxiliary Security Police during the German occupation. In 1950, Detlavs emigrated from Munich, Germany, as displaced refugee, with his pregnant wife and young daughter. The family immigrated to the United States and settled in Baltimore. In October 1976, the Office of Special Investigations, US Department of Justice, accused Detlavs of war crimes and the US Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) filed a deportation action. After four days of hearings, the Honorable Martin J. Travers, the federal immigration judge for the case, announced a continuance so the prosecution could obtain more evidence from Soviet sources. In June 1978, while Judge Travers was on assignment in the US Virgin Islands, part of his circuit at the time, he was stabbed to death. New hearings in the Detlavs trial were held in November 1978 and January 1979. While Detlavs admitted being a member of the Latvian Legion, he denied committing any crimes. Judge Emil Bobek denounced Detlavs for his lack of credibility, but ruled that the identification of Detlavs as a perpetrator was not reliable and a lie was not enough to warrant deportation. The ruling was upheld on appeal.

Drawing of Holocaust survivor testifying at trial of suspected Latvian war criminal

Object

Courtroom drawing created by Charles (Hap) Hazard while on assignment for the Baltimore Sun newspaper during the November 1977 deportation trial of Karlis Detlavs held in Baltimore, Maryland. It depicts Detlavs, Holocaust survivor and prosecution witness, Boris Tsesvan, and Yiddish interpreter, Moses Aberbach. Tsesvan identified Detlavs as one of the uniformed guards who beat and took away another Jewish forced laborer from the Hotel Roma in Riga, Latvia, in June 1943. Detlavs was accused of withholding information on his petition for permanent residency by denying involvement in Nazi war crimes during World War II (1939-1945). He was accused of executing Jews in the Riga ghetto and selecting Jews for execution in the Dwinsk ghetto in 1943, while a member of the Latvian Auxiliary Security Police during the German occupation. In 1950, Detlavs emigrated from Munich, Germany, as displaced refugee, with his pregnant wife and young daughter. The family immigrated to the United States and settled in Baltimore. In October 1976, the Office of Special Investigations, US Department of Justice, accused Detlavs of war crimes and the US Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) filed a deportation action. After four days of hearings, the Honorable Martin J. Travers, the federal immigration judge for the case, announced a continuance so the prosecution could obtain more evidence from Soviet sources. In June 1978, while Judge Travers was on assignment in the US Virgin Islands, part of his circuit at the time, he was stabbed to death. New hearings in the Detlavs trial were held in November 1978 and January 1979. While Detlavs admitted being a member of the Latvian Legion, he denied committing any crimes. Judge Emil Bobek denounced Detlavs for his lack of credibility, but ruled that the identification of Detlavs as a perpetrator was not reliable and a lie was not enough to warrant deportation. The ruling was upheld on appeal.

Drawing of guards and JDL protestors at trial of suspected Latvian war criminal

Object

Courtroom drawing created by Charles (Hap) Hazard while on assignment for the Baltimore Sun newspaper during the November 1977 deportation trial of Karlis Detlavs held in Baltimore, Maryland. It depicts three courtroom officers approaching three Jewish Defense League (JDL) members protesting the Honorable Martin J. Travers, the federal immigration judge for the case, issuing a continuance to allow the prosecution to seek more evidence from Soviet sources. Detlavs was accused of withholding information on his petition for permanent residency by denying involvement in Nazi war crimes during World War II (1939-1945). He was accused of executing Jews in the Riga ghetto and selecting Jews for execution in the Dwinsk ghetto in 1943, while a member of the Latvian Auxiliary Security Police during the German occupation. In 1950, Detlavs emigrated from Munich, Germany, as displaced refugee, with his pregnant wife and young daughter. The family immigrated to the United States and settled in Baltimore. In October 1976, the Office of Special Investigations, US Department of Justice, accused Detlavs of war crimes and the US Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) filed a deportation action. When Judge Travers announced the continuance, after four days of hearings, the JDL attendees began shouting at him and were thrown from the courtroom. In June 1978, while Judge Travers was on assignment in the US Virgin Islands, part of his circuit at the time, he was stabbed to death. New hearings in the Detlavs trial were held in November 1978 and January 1979. While Detlavs admitted being a member of the Latvian Legion, he denied committing any crimes. Judge Emil Bobek denounced Detlavs for his lack of credibility, but ruled that the identification of Detlavs as a perpetrator was not reliable and a lie was not enough to warrant deportation. The ruling was upheld on appeal.

Drawing of lawyer questioning eyewitness at trial of accused Latvian war criminal

Object

Courtroom drawing created by Charles (Hap) Hazard while on assignment for the Baltimore Sun newspaper during the November 1977 deportation trial of Karlis Detlavs held in Baltimore, Maryland. It depicts Detlavs's lawyer questioning an unseen person, while standing next to a seated Detlavs and his daughter in a crowded courtroom. Detlavs was accused of withholding information on his petition for permanent residency by denying involvement in Nazi war crimes during World War II (1939-1945). He was accused of executing Jews in the Riga ghetto and selecting Jews for execution in the Dwinsk ghetto in 1943, while a member of the Latvian Auxiliary Security Police during the German occupation. In 1950, Detlavs emigrated from Munich, Germany, as displaced refugee, with his pregnant wife and young daughter. The family immigrated to the United States and settled in Baltimore. In October 1976, the Office of Special Investigations, US Department of Justice, accused Detlavs of war crimes and the US Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) filed a deportation action. After four days of hearings, the Honorable Martin J. Travers, the federal immigration judge for the case, announced a continuance so the prosecution could obtain more evidence from Soviet sources. In June 1978, while Judge Travers was on assignment in the US Virgin Islands, part of his circuit at the time, he was stabbed to death. New hearings in the Detlavs trial were held in November 1978 and January 1979. While Detlavs admitted being a member of the Latvian Legion, he denied committing any crimes. Judge Emil Bobek denounced Detlavs for his lack of credibility, but ruled that the identification of Detlavs as a perpetrator was not reliable and a lie was not enough to warrant deportation. The ruling was upheld on appeal.

Drawing of judge at trial of suspected Latvian war criminal

Object

Courtroom drawing depicting Judge Emil Bobek created by Charles (Hap) Hazard while on assignment for the Baltimore Sun newspaper during the 1979 deportation trial of Karlis Detlavs held in Baltimore, Maryland. Detlavs was accused of withholding information on his petition for permanent residency by denying involvement in Nazi war crimes during World War II (1939-1945). He was accused of executing Jews in the Riga ghetto and selecting Jews for execution in the Dwinsk ghetto in 1943, while a member of the Latvian Auxiliary Security Police during the German occupation. In 1950, Detlavs emigrated from Munich, Germany, as displaced refugee, with his pregnant wife and young daughter. The family immigrated to the United States and settled in Baltimore. In October 1976, the Office of Special Investigations, US Department of Justice, accused Detlavs of war crimes and the US Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) filed a deportation action. In November 1977, after four days of hearings, the Honorable Martin J. Travers, the federal immigration judge for the case at the time, announced a continuance so the prosecution could obtain more evidence from Soviet sources. In June 1978, while Judge Travers was on assignment in the US Virgin Islands, part of his circuit at the time, he was stabbed to death. New hearings in the Detlavs trial were held in November 1978 and January 1979. While Detlavs admitted being a member of the Latvian Legion, he denied committing any crimes. Judge Emil Bobek denounced Detlavs for his lack of credibility, but ruled that the identification of Detlavs as a perpetrator was not reliable and a lie was not enough to warrant deportation. The ruling was upheld on appeal.

Sketch of three spectators at trial of accused Latvian war criminal

Object

Courtroom drawing created by Charles (Hap) Hazard while on assignment for the Baltimore Sun newspaper during the 1979 deportation trial of Karlis Detlavs held in Baltimore, Maryland. The drawing depicts three courtroom spectators, including a man wearing a kippah. Detlavs was accused of withholding information on his petition for permanent residency by denying involvement in Nazi war crimes during World War II (1939-1945). He was accused of executing Jews in the Riga ghetto and selecting Jews for execution in the Dwinsk ghetto in 1943, while a member of the Latvian Auxiliary Security Police during the German occupation. In 1950, Detlavs emigrated from Munich, Germany, as displaced refugee, with his pregnant wife and young daughter. The family immigrated to the United States and settled in Baltimore. In October 1976, the Office of Special Investigations, US Department of Justice, accused Detlavs of war crimes and the US Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) filed a deportation action. In November 1977, after four days of hearings, the Honorable Martin J. Travers, the federal immigration judge for the case at the time, announced a continuance so the prosecution could obtain more evidence from Soviet sources. In June 1978, while Judge Travers was on assignment in the US Virgin Islands, part of his circuit at the time, he was stabbed to death. New hearings in the Detlavs trial were held in November 1978 and January 1979. While Detlavs admitted being a member of the Latvian Legion, he denied committing any crimes. Judge Emil Bobek denounced Detlavs for his lack of credibility, but ruled that the identification of Detlavs as a perpetrator was not reliable and a lie was not enough to warrant deportation. The ruling was upheld on appeal.

Drawing of defendant and US attorney at trial of suspected Latvian war criminal

Object

Courtroom drawing created by Charles (Hap) Hazard while on assignment for the Baltimore Sun newspaper during the 1979 deportation trial of Karlis Detlavs held in Baltimore, Maryland. The drawing depicts Detlavs on the witness stand begin questioned by United States attorney George Parker through a court-appointed Latvian interpreter. Detlavs was accused of withholding information on his petition for permanent residency by denying involvement in Nazi war crimes during World War II (1939-1945). He was accused of executing Jews in the Riga ghetto and selecting Jews for execution in the Dwinsk ghetto in 1943, while a member of the Latvian Auxiliary Security Police during the German occupation. In 1950, Detlavs emigrated from Munich, Germany, as displaced refugee, with his pregnant wife and young daughter. The family immigrated to the United States and settled in Baltimore. In October 1976, the Office of Special Investigations, US Department of Justice, accused Detlavs of war crimes and the US Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) filed a deportation action. In November 1977, after four days of hearings, the Honorable Martin J. Travers, the federal immigration judge for the case at the time, announced a continuance so the prosecution could obtain more evidence from Soviet sources. In June 1978, while Judge Travers was on assignment in the US Virgin Islands, part of his circuit at the time, he was stabbed to death. New hearings in the Detlavs trial were held in November 1978 and January 1979. While Detlavs admitted being a member of the Latvian Legion, he denied committing any crimes. Judge Emil Bobek denounced Detlavs for his lack of credibility, but ruled that the identification of Detlavs as a perpetrator was not reliable and a lie was not enough to warrant deportation. The ruling was upheld on appeal.

Drawing of Holocaust survivor testifying at trial of accused Latvian war criminal

Object

Courtroom drawing created by Charles (Hap) Hazard while on assignment for the Baltimore Sun newspaper during the 1979 deportation trial of Karlis Detlavs held in Baltimore, Maryland. It depicts eyewitness Frida Michelson testifying that Detlavs was the guard who forced her to the execution pit during the massacre in the Rumbula Forest in December 1941. Michelson survived by hiding under a pile of discarded shoes. She identified Detlavs from a 1941 photo shown to her by Israeli police in the 1970s, but did not identify him in person at the trial. Detlavs was accused of withholding information on his petition for permanent residency by denying involvement in Nazi war crimes during World War II (1939-1945). He was accused of executing Jews in the Riga ghetto and selecting Jews for execution in the Dwinsk ghetto in 1943, while a member of the Latvian Auxiliary Security Police during the German occupation. In 1950, Detlavs emigrated from Munich, Germany, as displaced refugee, with his pregnant wife and young daughter. The family immigrated to the United States and settled in Baltimore. In October 1976, the Office of Special Investigations, US Department of Justice, accused Detlavs of war crimes and the US Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) filed a deportation action. In November 1977, after four days of hearings, the Honorable Martin J. Travers, the federal immigration judge for the case at the time, announced a continuance so the prosecution could obtain more evidence from Soviet sources. In June 1978, while Judge Travers was on assignment in the US Virgin Islands, part of his circuit at the time, he was stabbed to death. New hearings in the Detlavs trial were held in November 1978 and January 1979. While Detlavs admitted being a member of the Latvian Legion, he denied committing any crimes. Judge Emil Bobek denounced Detlavs for his lack of credibility, but ruled that the identification of Detlavs as a perpetrator was not reliable and a lie was not enough to warrant deportation. The ruling was upheld on appeal.

Drawing of accused Latvian war criminal on the stand

Object

Courtroom drawing created by Charles (Hap) Hazard while on assignment for the Baltimore Sun newspaper during the 1979 deportation trial of Karlis Detlavs held in Baltimore, Maryland. It depicts defendant Karlis Detlavs on the witness stand. Detlavs was accused of withholding information on his petition for permanent residency by denying involvement in Nazi war crimes during World War II (1939-1945). He was accused of executing Jews in the Riga ghetto and selecting Jews for execution in the Dwinsk ghetto in 1943, while a member of the Latvian Auxiliary Security Police during the German occupation. In 1950, Detlavs emigrated from Munich, Germany, as displaced refugee, with his pregnant wife and young daughter. The family immigrated to the United States and settled in Baltimore. In October 1976, the Office of Special Investigations, US Department of Justice, accused Detlavs of war crimes and the US Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) filed a deportation action. In November 1977, after four days of hearings, the Honorable Martin J. Travers, the federal immigration judge for the case at the time, announced a continuance so the prosecution could obtain more evidence from Soviet sources. In June 1978, while Judge Travers was on assignment in the US Virgin Islands, part of his circuit at the time, he was stabbed to death. New hearings in the Detlavs trial were held in November 1978 and January 1979. While Detlavs admitted being a member of the Latvian Legion, he denied committing any crimes. Judge Emil Bobek denounced Detlavs for his lack of credibility, but ruled that the identification of Detlavs as a perpetrator was not reliable and a lie was not enough to warrant deportation. The ruling was upheld on appeal.