Overview

- Description

- The Hana and Charles Bruml papers consist of biographical materials, correspondence, personal narratives, photographic materials, printed materials, and Theresienstadt materials documenting Hana and Charles Bruml from Czechoslovakia, their families, their survival in Theresienstadt and Auschwitz, and their immigration to the United States after the Holocaust.

Biographical materials consist of birth, marriage, and death certificates; school records; identification papers; displaced persons records; and immigration and citizenship records documenting the Bruml family (Hana, Charles, Irma, Jindrich, Otto, and Richard), the Müller family (Richard and Hedwig), the Schiff family (Karel, Marta, Richard, Rudolf), Karel Fischer, and Bruno Mandl. This series also includes family trees; correspondence documenting efforts to trace the fates of member of the Müller, Schindler, Raiman, and Epstein families; immigration materials; and an untitled list of names including Karel Fischer’s.

Correspondence files primarily comprise letters exchanged between Hana and Charles Bruml during the months between her immigration to the United States in May 1946 and their marriage at the end of the year. Additional postwar correspondence with family members, friends, and colleagues relates Holocaust experiences, documents immigration plans, and shares information about psychological investigations. A handful of 19th century letters to Julie Fraenkel convey birthday wishes from her husband and son. A postcard and letter from Karel Fischer document his World War I service in Przemyśl and postwar experiences in Vladivostok. Letters and telegrams document Richard Bruml’s political imprisonment in Rottenburg am Neckar in 1941 and 1942 and his death. Postcards from Otto Bruml describe his life in Theresienstadt in 1943.

Personal narratives relate the Holocaust and immigration experiences of Charles Bruml, Edith Lowy, and three unidentified survivors. The narratives describe prewar life in Czechoslovakia, survival in Theresienstadt, Auschwitz, and the Skarżysko-Kamienna labor camp, and arrival in New York after the war.

Photographic materials consist of prewar and postwar photographs of family members and friends. This series also includes a photograph album, Kultura v Terezine, created by George Lauscher and documenting a memorial exhibition about Theresienstadt.

Printed materials include May 1945 copies of 21 Army Group News Bulletin and Die Mitteilungen, as well as clippings, articles, and speeches about the Holocaust. This series also includes an unbound copy of the pamphlet Jak si terezínští heftlinkové představovali, že bude vypadat československé státní zřízení, and a copy of an American Temperance Society display order form.

Theresienstadt materials comprise photostats and photocopies of drawings and maps of Theresienstadt, a road project for a street leading to a crematorium, and a report about food supplies and deaths at Theresienstadt dated March 1942. The drawings and maps were prepared by Charles Bruml in his role in the technical department at Theresienstadt. - Date

-

inclusive:

circa 1880-2001

- Credit Line

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection, Gift of Hana Bruml

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection, Gift of Charles and Hana Bruml

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection, Gift of the Estate of Hana Bruml - Collection Creator

- Hana Bruml

Charles Bruml - Biography

-

Hana Müller (Mueller; later Bruml) was born May 30, 1922, to Richard and Hedvika Zappner Müller in Prague, Czechoslovakia (Czech Republic). Her father was born in 1885 in Chocen, Czech Republic, Austro-Hungary, to Emanuel and Antonia Müller. Richard was a tinsmith and owned a workshop. Her mother was born April 17, 1891, in Prague, to Isidor and Marie Heller Zappner, and had one sister, Gizela, born 1888. Hana’s maternal grandparents, Isidor and Marie (b.1856), lived with her family in the Jewish quarter; Isador died in 1925. The family was prosperous and employed a maid. They spoke Czech and German. Hana attended a Zionist school, then a Czech school. She attended business school for a year and worked as a typist.

From 1933, when the Nazi regime came to power in Germany, Prague saw a large influx of Jews fleeing persecution. In September 1938, Germany annexed the Sudetenland border region. In March 1939, Germany annexed the Czech provinces of Bohemia and Moravia, which included Prague, which were governed by a Reich Protector. Other regions were absorbed by German allies and Czechoslovakia ceased to exist. Jews lost their jobs and their property. Hana’s father’s workshop was confiscated. He could not find work and it was difficult to get enough food. Hana tried to leave, but could not get a US visa or German passport. On September 1, Germany invaded neighboring Poland. Jewish men could be conscripted for forced labor at any time. On November 14, 1939, Hana married Rudolf Schiff, b.1919, at City Hall. They got their own room when one of the families boarded at Rudolf’s parent's home was relocated. Hana began working for the Palestine Office, which facilitated emigration to Mandate Palestine.

In September 1941, Heydrich, SS Chief of RSHA, became Reich Protector, and prioritized the expulsion of Jews to concentration camps. Jews were required to wear a yellow Star of David badge at all times to make them easy to identify. Transports were announced daily in the papers. Rudolf and Hana learned that the transports were going to a camp in Terezin, Theresienstadt in German, about 40 miles north of Prague. Rudolf contracted scarlet fever and was hospitalized for several months. On July 20, 1942, Hana’s parents, Richard and Hedvika, and her grandmother Marie were sent to Theresienstadt. On August 10, 1942, Rudolf and Hana received transport notices. At the train station, they were assigned prisoner numbers, 984 and 1101, and taken to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp. Her parents told Hana that her grandmother Marie had died on August 3, and was buried in a mass grave. Rudolf was still sickly and was not assigned to work. Hana was well-connected and knew the nickname of the head of the labor department and used this information to get assigned as a nurse at the camp hospital. Men and women were housed apart and Hana lived with 8 nurses near the hospital. Rations were watery soup, and twice a week, a dumpling. Hana traded her wedding ring for extra bread and at times bought food on the black market. She worked 12 hour shifts, 6 nights a week, assisting the 4 doctors, cleaning the hospital and patients, and administering the small quantity of poor quality medicine. She was often charged with caring for the elderly and the terminally ill. The overcrowding, lack of food, and poor sanitary conditons in the camp aided the spread of disease and thousands died every month. Hana was given small, hard, pieces of caked soap that did not clean well, but it was all she had for herself, her clothing, and often, for the hospital. She became an infectious disease nurse, and received extra food and occasional access to a bathtub. She visited Richard, whose health had worsened, when she could and gave him much of her extra food. Their marriage was strained and eventually she told him she considered it over. On October 8, 1942, Hana’s parents, Richard and Hedvika, were deported east. In late 1942, several members of Hana’s extended family arrived, including her cousins Jiri and Irma Lauscher and their daughter Michaela, age 5. Several family members were deported east soon after arrival. Hana developed a relationship with a Jewish Czech doctor, Bruno Mandl (b.1912), and they planned to marry after the war.

On July 5, 1943, Rudolf’s parents, Richard and Marta, arrived at the camp, and his brother Karel on September 11. On December 15, 1943, Rudolf, Richard, Marta, and Karel were deported to Auschwitz. On October 1, 1944, Bruno was deported and Hana volunteered to go with him. They were put on a dirty, overcrowded train to Auschwitz in German occupied Poland. As they neared the camp, the inmates told new arrivals to throw their belongings to them over the fences. A female prisoner did so, and was shot by a guard. She was the first person Hana saw killed in a camp. The new arrivals were directed to go left or right by a man wearing white gloves. Bruno was sent right. Hana asked to go with him and was shoved left. She was directed to a room and ordered to undress and line up to see if she was pregnant. Her hair was shaved and she had to take a cold shower. While she was showering, someone stole her last possession, a pair of warm boots. She was issued a filthy striped uniform and wooden clogs. She shared a pallet and a blanket with 4 other women in her barrack. Later that month, a man came to the barracks and chose Hana and 3 of her friends for labor. The women were given new uniforms and transported to Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp, a sub-camp of Gross-Rosen concentration camp in Poland. Hana was placed in an unheated barrack run by a cruel Sudeten German woman. Rations were small and they gave themselves hope by talking of the food they would make if they could. The factory was on the other side of the town and the walk was so cold that Hana turned a sock into gloves that she shared with her friends from Auschwitz. She worked on a manufacturing line in a Vereinigte Deutsche Metallwerke factory where she made airplane parts, alongside Italian and Soviet prisoners of war and some German soldiers that were being punished. Hana worked in 12 hour shifts with female SS guards. The poor quality materials often broke and Hana would be blamed. She spent her long shifts worrying that she would not survive. In April 1945, the factory ran out of raw material and work was halted.

On May 5, 1945, the guards opened the camp gates and released the prisoners. Hana walked to the nearby Czech town of Nachod, where she was received warmly by the townspeople. On May 7, Germany surrendered. On May 8, Hana returned to Prague to look for her family. Hana’s mother and father, Hedvika and Richard, had been murdered at Treblinka killing center in 1942. Several family members, including her aunt Gizela and her husband and children, were killed upon arrival in Auschwitz in October 1942. Hana’s husband Rudolf and his family were killed upon arrival in December 1943. Her fiance Bruno had been killed when they arrived in Auschwitz in 1944. Her cousins, the Lauschers, returned to Prague from Theresienstadt. Hana changed her surname from Schiff to Suk. In order to claim her family’s property, Hana had to go to a government office to report them as deceased. While there, she met 33 year old Karel Bruml, born in Prague, who had survived Theresienstadt and several concentration camps. They planned to go to America and marry. In May 1946, Hana sailed to the US and went to live in New York City with a relative. In August, Karel arrived. On December 31, 1946, Hana and Karel, now Charles, married at City Hall. In 1947, the couple moved to Washington, D.C. Hana received a doctorate in clinical psychology and began a long, successful career. Charles was a commercial artist. The couple often returned to Prague to visit friends and family. Charles, 85, passed away on March 22, 1998, in Arlington, Virginia. Hana,78, passed away on August 7, 2000, in Arlington.

Karel (Charles) Bruml was born on October 5, 1912, to Jindrich and Irma Schindler Bruml in Prague, Czech Republic, Austro-Hungary. Jindrich was born in 1882 in Strazov to Abraham and Anna Steinreich Bruml and had approximately 10 siblings. Jindrich was a businessman and owned several shoe factories. Irma was born in 1885 in Trebenice to Jacob and Anna Getreuer Schindler. Karel had 2 younger siblings: Otto, b.1916, and Anna, b. 1922. Karel’s family was prosperous and employed a maid. They spoke Czech and German. They were Jewish, but did not keep kosher and rarely attended synagogue. Karel attended a Czech school and took art classes at his synagogue and with a private teacher. Karel’s father often partnered with his brother Richard, b.1884, on business deals. Richard was married to Helene Fischer and Karel was very close to her brother Karel Fischer (1889-1975), a railroad engineer and transportation expert, whom he thought of as an uncle. Karel was a draftsman at a design company.

On September 29, 1938, Germany annexed the Sudetenland border region. On March 15, 1939, Germany invaded Prague and absorbed the Bohemia and Moravia provinces, which were governed by a Reich Protector. Karel’s uncle Richard was secretary of the Pilsen branch of the Czechoslovakian Social Democratic party, and was jailed in Germany as a political prisoner. Several antisemitic regulations were enacted: Jews lost their jobs and property; were banned from areas of the city or shopping at certain times. Karel was fired because he was a Jew and his father’s businesses were confiscated. The family had to turn their radio and valuables over to the authorities. Jews were not allowed to have gold or silver, so Karel’s father hid jewelry and bought cheap jewelry to turn over instead. On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded neighboring Poland, and World War II began when Great Britain and France declared war.

In September 1941, Reinhard Heydrich, SS chief of Reich security, became Reich Protector. Jews were required to wear Star of David badges to make them easy to identify. Mass deportations of Jews from Prague began. Karel Fischer was deported in the first transport in late November to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp, 40 miles north of Prague. On December 10, Karel, his parents, Jindrich and Irma, his siblings, Otto and Anna, and Otto’s wife, Irma, b.1920, were sent to Theresienstadt. Karel was separated from his family and placed in a barrack with members of the Judenrat (Jewish Council), including Fischer. Fischer was also in charge of transportation and railroad construction for the camp. Fischer arranged for Karel to get a job in the ghetto order police. Karel stood on a street corner and directed the flow of people moving around the camp. Fischer later got Karel a position in the camp technical department. He recorded statistics and made charts and graphs for the German SS camp command. Karel had to report the statistics to the commandant, and sometimes got yelled at or threatened if the statistics were not to his liking. After one report, Karel witnessed 7 men get executed for crimes including writing to a family member and possessing cigarettes. It was a large department and, in their free time, the artists who worked there could secretly do work of their own. The department was headed by Bedrich Fritta and Karel also worked with Leo Haas, Peter Kien, and Jiri Lauscher. Karel’s father and brother worked in the kitchens, preparing the watery soup that was the main food. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and his sister Anna were selected for deportation. Karel tried to convince the camp authorities that his job recording statistics made him indispensable, and thus his family should be allowed to stay in the camp with him. This did not work, so Karel volunteered to be deported with them. They were put on separate cattle cars on a filthy, overcrowded train car. Karel was nominated as the leader of his car. The train never stopped and there was no food. There was a single barrel for a toilet and an elderly man died while using it. When the train arrived at Auschwitz concentration camp in German occupied Poland, Karel had to remove the man’s body. When he returned to the platform, he was unable to find his family.

Karel was given a striped uniform and a new prisoner number, 71061, was tattooed on his forearm. After a week, Karel was sent on a forced march to Auschwitz III – Monowitz (Buna) concentration camp. He was given soup when he arrived at the camp, but it tasted so terrible that he couldn’t eat it and gave it to other inmates who told him that it would taste good soon enough. He was placed on a work crew that moved concrete and bricks in 12 hour shifts. Shortly after Karel arrived, several camp guards were looking for someone to draw a birthday card for their commander. Karel found a pencil and paper and drew the card for them. This was a risky thing to do, because if the commander did not like the card, he would be killed. The commander liked the card and, as a reward, Karel was placed on a new work team. He painted numbers on uniforms. This was a very good job, and allowed him to paint a new, lower Buna number, 107310, on his cap. This made it appear as though he had been in the camp a long time and had some authority. He was eventually replaced by a German opera singer. He was given a new job tracking statistics for I.G. Farben, the German company that used camp slave labor to produce rubber. Karel continued painting numbers during the evenings to get extra soup. On January 18, 1945, the camp was evacuated as the Russians closed in. Karel was sent on a 2 day forced march to Gleiwitz, an Auschwitz subcamp. He stuffed rags in his shirt to stay warm. He then was placed on an open-air cattle car to Nordhausen, a Mittelbau-Dora subcamp in Germany. Karel did not get assigned to work right away, so he hid in a haystack for 10 days. When he came out, he was recognized by a capo, who had Karel draw pictures for him. Karel worked with other artists instead of on a construction crew. In March, Karel was placed on a 4 day transport to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. In late March or early April, Karel and a group of friends escaped from the camp through an unlocked door. They went to a farmhouse, where they were given food and a place to sleep. Karel stayed at the farmhouse until British soldiers arrived and told him that he had to return to Bergen-Belsen, which had been liberated by British troops on April 15, 1945.

On May 7, Germany surrendered. Karel worked for UNRRA, the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration in the camp, but after 3 weeks returned to Prague to look for his family. Karel’s mother, father, and sister, Irma, Jindrich, and Anna, were killed at Auschwitz in late October 1942. His brother, sistein-law, and aunt, Otto, Irma, and Helene Fischer, were deported to Auschwitz in September 1944. Irma and Helene were killed upon arrival. Otto died in 1945 at Buchenwald. Karel’s uncle Richard was reported as having committed suicide in prison in May 1942. Karel Fischer, his wife, and his mother returned to Prague from Theresienstadt. In order to claim his family’s property, Karel had to report them as deceased at a government office. While at the office, Karel met 23 year old Hana Schiff Suk (1922 – 2000), a survivor of Theresienstadt and Kadowa-Sackisch slave labor camp. They decided to go to America and marry. Hana left for New York in May 1946. On August 1946, Karel flew to New York City to join her. They married on December 31, 1946. Karel, now Charles, and Hana moved to Washington, D.C. in 1947. Charles completed art school and was a commercial artist and art director. Hana earned a doctorate and was a clinical psychologist. The couple often returned to Prague to visit friends and family. Charles, 85, passed away on March 22, 1998, in Arlington, Virginia.

Physical Details

- Genre/Form

- Photographs.

- Extent

-

2 boxes

7 oversize folders

1 oversize box

- System of Arrangement

- The Hana and Charles Bruml papers are arranged as six series: I. Biographical materials, 1892-1999 , II. Correspondence, 1856-1987, III. Personal narratives, approximately 1945-1987, IV. Photographic materials, approximately 1880-2001, V. Printed materials, approximately 1945-1991, VI. Theresienstadt materials, approximately 1942

Rights & Restrictions

- Conditions on Access

- There are no known restrictions on access to this material.

- Conditions on Use

- The donor, source institution, or a third party has asserted copyright over some or all of the material(s) in this collection. You do not require further permission from the Museum to use this material. The user is solely responsible for making a determination as to if and how the material may be used.

- Copyright Holder

- Ms. Ruth Kraemer

Keywords & Subjects

- Topical Term

- Jews--Czech Republic--Prague. Holocaust survivors--New York (State)--New York. Holocaust survivors--Washington (D.C.) Holocaust, Jewish (1939-1945)--Personal narratives. Political prisoners--Germany--Rottenburg am Neckar. World War, 1914-1918--Participation, Jewish. Women psychologists.

Administrative Notes

- Holder of Originals

-

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Legal Status

- Permanent Collection

- Provenance

- Hana and Charles Bruml and Ruth Kraemer donated the Hana and Charles Bruml papers to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in 1989, 2000, 2001, and 2011. Accessions previously cataloged as 2000.354.1, 2001.3, and 2011.445.1 have been incorporated into this collection.

- Funding Note

- The cataloging of this collection has been supported by a grant from the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany.

- Primary Number

- 1989.303.57

- Record last modified:

- 2024-01-31 09:31:28

- This page:

- https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn90446

Additional Resources

Download & Licensing

In-Person Research

- Available for Research

- Plan a Research Visit

-

Request in Shapell Center Reading Room

Bowie, MD

Contact Us

Also in Charles and Hana Bruml family collection

The collection consists of artwork, Star of David badges, clothing, drafting tools, a drawing, Theresienstadt scrip, correspondence, documents and photographs relating to the experiences of Charles (Karel) Bruml and Hana Mueller Schiff Sukova Bruml in prewar Prague, Czechoslovakia, and in Theresienstadt ghetto/labor camp and several concentration camps during the Holocaust, and in Czechoslovakia and the United States after the Holocaust.

Date: approximately 1880-2001

Wooden drafting triangle used by a Czech Jewish camp inmate

Object

Wooden right angle (45 degree) drafting triangle used by Karel Bruml when he worked as a printer and draftsman in the technical department at Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp from January-October 1942. It is also scratched with the name of his uncle Karel Fischer, an engineer in charge of railroad construction in the camp from November 1941-May 1945. Karel left this and other items with his uncle when he was deported. Karel and his uncle were from Prague, which, in March 1939, was annexed by Nazi Germany. On December 10, 1941, Karel, 29, his parents, Jindrich and Irma, his siblings, Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were transported to Theresienstadt. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz, but separated during the journey. His parents and sisters were killed. Karel was tattooed and then force marched to Auschwitz III-Monowitz (Buna) where he painted numbers on prisoner uniforms. On January 18, 1945, as Soviet troops approached, Karel was sent to Gleiwitz, Dora-Mittelbau, and Bergen-Belsen where he was liberated on April 15, 1945. He returned to Prague and met his future wife, Hana Schiff Suk, as they both searched for news of their families, and found few survivors. Hana had survived Theresienstadt, Auschwitz, and Kudowa-Sackisch camps. Charles and Hana left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

French curve drafting tool used by a Czech Jewish camp inmate

Object

French curve drafting tool used by Karel Bruml when he worked as a printer and draftsman in the technical department at Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp from January-October 1942. When Karel was deported, he left this and other items with his uncle Karel Fischer, an engineer in charge of railroad construction in the camp from November 1941-May 1945. Both were from Prague, which, in March 1939, was annexed by Nazi Germany. On December 10, 1941, Karel, 29, his parents, Jindrich and Irma, his siblings, Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were transported to Theresienstadt. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz, but separated during the journey. His parents and sisters were killed. Karel was tattooed and then force marched to Auschwitz III-Monowitz (Buna) where he painted numbers on prisoner uniforms. On January 18, 1945, as Soviet troops approached, Karel was sent to Gleiwitz, Dora-Mittelbau, and Bergen-Belsen where he was liberated on April 15, 1945. He returned to Prague and met his future wife, Hana Schiff Suk, as they both searched for news of their families, and found few survivors. Hana had survived Theresienstadt, Auschwitz, and Kudowa-Sackisch camps. Charles and Hana left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Wooden tile with Terezin coat of arms made by a Czech Jewish inmate

Object

Ornament with the Terezin shield made by Jiri Lauscher. It is similar to crafts he made while working in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp, but the date this piece was made is unknown. At some point after the war, he gave the tile to his cousins Hana and Charles Bruml, both former camp inmates. Jiri and Karel worked together in the camp technical department. They were all from Prague which, in March 1939, was annexed by Nazi Germany. In December 1942, Jiri, his wife Irma, and daughter Michaela, 5, were sent to Theresienstadt, where they were liberated in early May 1945. Jiri and family returned to Prague and discovered that most of their relatives had been killed in German concentration camps. Karel was sent to the camp in December 1941 with his parents, Jindrich and Irma, sister Anna, and brother Otto and his wife. On January 11, 1942, Karel volunteered to be deported with his parents and sister. They were sent to Auschwitz; his family was killed and Karel was transferred to Auschwitz III-Monowitz (Buna). In January 1945, Karel was sent to Gleiwitz, Dora-Mittelbau, and Bergen-Belsen where he was liberated on April 15. Hana and husband Rudolf Schiff were sent to Terezin in August 1942. Rudolf was deported to Auschwitz in December 1943 and killed. In October 1944, Hana was deported to Auschwitz, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp were she was liberated in April 1945. Hana and Karel met in postwar Prague while searching for news of their families. They found few survivors. Karel and Hana left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Zebra push puppet made by a former Jewish Czech camp inmate

Object

Wooden push puppet toy zebra, a type of toy known as a wakouwa, made by Jiri Lauscher after the war and given to his cousins Charles (Karel) and Hana Bruml. When Jiri, his wife, and daughter Michaela, 5, arrived at Theresiensradt ghetto-labor camp in December 1942, Jiri was asked his profession. Michaela had brought Pluto, her push puppet dog, which Jiri had made in the carpenter's workshop where he worked after being fired from his previous job for being Jewish. This proof of his useful skills helped make sure the family got sent to Theresienstadt, and not deported east. Jiri and Karel were assigned to the camp technical department. Jiri and the Bruml's were from Prague which, in March 1939, was annexed by Nazi Germany. In December 1942, Jiri, his wife Irma, and Michaela were sent to Theresienstadt and remained there until liberation in early May 1945. Most of their relatives were killed in German concentration camps. Karel, 29, was sent to the camp in December 1941 with his parents, Jindrich and Irma, sister Anna, and brother Otto and his wife. On January 11, 1942, Karel volunteered to be deported with his parents and sister. They were sent to Auschwitz; his family was killed and Karel was marched to Auschwitz III-Monowitz (Buna). In January 1945, Karel was sent to Gleiwitz, Dora-Mittelbau, and Bergen-Belsen where he was liberated on April 15. Hana, 20, and her first husband Rudolf Schiff were sent to Terezin in August 1942. Rudolf was deported to Auschwitz in December 1943 and killed. In October 1944, Hana was deported to Auschwitz, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp where she was liberated in April 1945. Hana and Karel met in postwar Prague while searching for news of their families. They found few survivors. Karel and Hana left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Metal tablespoon used by a Jewish Czech concentration camp inmate

Object

Tablespoon taken from a bag of spoons at Auschwitz by Hana Mueller Schiff, 22. She took it so she could eat like a person. She used it there and at Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp, October 1944-April 1945. Hana was from Prague which, in March 1939, was annexed by Nazi Germany. Heydrich, SS Chief of RSHA, became Reich Protector in September 1941 and ordered the construction of a ghetto-labor camp in Terezin. On November 24, 1941, the first transports of Jewish prisoners arrived. On July 20, 1942, Hana’s parents Hedvika and Richard Mueller and her grandmother Marie Zappner were sent to the camp. On August 10, 1942, Hana and her husband Rudolf Schiff were transported. That October, Hana's parents were deported to Treblinka killing center. In December 1943, Hana's husband, with his parents and brother, was sent to Auschwitz and killed. On October 1, 1944, Hana was deported to Auschwitz, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch where she made airplane parts. She was liberated on May 5, 1945. Karel Bruml, 29, was sent to Terezin in December 1941 with his parents, Jindrich and Irma, sister Anna, and brother Otto and his wife. On January 11, 1942, Karel volunteered to be deported with his parents and sister. They were sent to Auschwitz; his family was killed and Karel was tattooed and sent to Auschwitz III-Monowitz (Buna). In January 1945, Karel was sent to Gleiwitz, Dora-Mittelbau, and Bergen-Belsen where he was liberated on April 15. Hana and Karel met in postwar Prague while searching for news of their families. They found few survivors. Karel and Hana left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Burlap purse made from a mattress cover by a Jewish Czech concentration camp inmate

Object

Brown burlap bag made from a mattress cover by Hana Mueller Schiff, 22, at Auschwitz and used there and at Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp, October 1944-May 1945. Hana was from Prague which, in March 1939, was annexed by Nazi Germany. Heydrich, SS Chief of RSHA, Reich Main Security, became Reich Protector in September 1941 and ordered the construction of a ghetto-labor camp in Terezin and on November 24, 1941, the first transports of Jewish prisoners reached the camp. On July 20, 1942, Hana’s parents Hedvika and Richard Mueller and her grandmother Marie Zappner were sent to the camp. On August 10, 1942, Hana and her husband Rudolf Schiff were transported. That October, Hana's parents were deported to Treblinka killing center. In December 1943, Hana's husband, with his parents and brother, was sent to Auschwitz and killed. On October 1, 1944, Hana was deported to Auschwitz, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch where she made airplane parts. She was liberated on May 5, 1945. Karel Bruml, 29, was sent to Terezin in December 1941 with his parents, Jindrich and Irma, sister Anna, and brother Otto and his wife. On January 11, 1942, Karel volunteered to be deported with his parents and sister. They were sent to Auschwitz; his family was killed and Karel was tattooed and sent to Auschwitz III-Monowitz (Buna). In January 1945, Karel was sent to Gleiwitz, Dora-Mittelbau, and Bergen-Belsen where he was liberated on April 15. Hana and Karel met in postwar Prague while searching for news of their families. They found few survivors. Karel and Hana left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Concentration camp uniform skirt worn by a Czech Jewish inmate

Object

Blue and gray striped winter issue uniform skirt issued to Hana Bruml at Auschwitz concentration camp in October 1944. Hana shortened the skirt and made two pockets with the extra fabric. She wore it until liberated from Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp in May 1945. Hana was from Prague which, in March 1939, was annexed by Nazi Germany. Heydrich, SS Chief of RSHA, became Reich Protector in September 1941 and ordered the construction of a ghetto-labor camp in Terezin and transports of Jewish prisoners began arriving on November 24, 1941. On July 20, 1942, Hana’s parents Hedvika and Richard Mueller and her grandmother Marie Zappner were sent to the camp. On August 10, 1942, Hana and her husband Rudolf Schiff were transported. That October, Hana's parents were deported to Treblinka killing center. In December 1943, Hana's husband, with his parents and brother, was sent to Auschwitz and killed. On October 1, 1944, Hana was deported to Auschwitz, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch where she made airplane parts. She was liberated on May 5, 1945. Karel Bruml, 29, was sent to Terezin in December 1941 with his parents, Jindrich and Irma, sister Anna, and brother Otto and his wife. On January 11, 1942, Karel volunteered to be deported with his parents and sister. They were sent to Auschwitz; his family was killed and Karel was tattooed and sent to Auschwitz III-Monowitz (Buna). In January 1945, Karel was sent to Gleiwitz, Dora-Mittelbau, and Bergen-Belsen where he was liberated on April 15. Hana and Karel met in postwar Prague while searching for news of their families. They found few survivors. Karel and Hana left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Concentration camp uniform cap with number 107310 issued to a Jewish Czech inmate

Object

Blue and gray striped concentration camp uniform cap issued to Karel Bruml while an inmate at Auschwitz III – Monowitz (Buna) concentration camp from November 1942 - January 1945. Karel demonstrated his artistic ability to the camp guards, and was put to work painting prisoner numbers on uniforms. He then painted a lower, more advantageous prisoner number, 107310, on his cap. Karel was from Prague which was annexed by Germany in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents, Jindrich and Irma, his siblings, Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were transported to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp. Karel was assigned to work in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. Karel was then force marched to Buna. He moved building materials until reassigned. In early 1945, Karel was transferred to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen concentration camps. On April 15, Bergen-Belsen was liberated by British soldiers. Karel returned to Prague after the war ended in early May. He learned that most of his family had perished. He met Hana Schiff Suk, who had survived Theresienstadt, Auschwitz, and Kudowa-Sackisch. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Patch with the Bohemian lion made by a Jewish Czech concentration camp inmate

Object

Cloth shield with the Bohemian lion with the Czech escutcheon on a red field made by Karel Bruml to identify himself as Czech. Karel made it while imprisoned in Nordhausen concentration camp, part of the Dora-Mittelbau complex, from February-March 1945, after a capo recognized him and had him make artwork work with a group of other artist-prisoners. Karel, 20, was from Prague in the Province of Bohemia which was annexed by Germany in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents, Jindrich and Irma, his siblings, Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were transported to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp. Karel was assigned to work in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Karel's parents and sister were murdered in the gas chambers upon arrival. Karel was then force marched to Auschwitz III-Monowitz (Buna) where he moved building materials until reassigned to paint prisoner numbers. In early 1945, Karel was transferred to Gleiwitz, then Nordhausen, and finally Bergen-Belsen concentration camps where he was liberated on April 15 by British soldiers. Karel returned to Prague after the war ended in early May. He learned that most of his family had perished. He met Hana Schiff Suk, who had survived Theresienstadt, Auschwitz, and Kudowa-Sackisch. They left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Inverted red triangle patch with T made by a Jewish Czech concentration camp inmate

Object

Inverted, triangular red prisoner identification badge with a black T for Tscheche [Czech] owned by Karel (later Charles) and Hana Bruml. Karel made it while imprisoned in Nordhausen concentration camp, part of the Dora-Mittelbau complex, from February-March 1945, after a capo recognized him and had him make artwork with a group of other artist-prisoners. Red cloth is usually used to identify political prisoners, with a letter to indicate nationality; if the inmate was Jewish, it would be worn with a yellow cloth stripe. Both Karel and Hana were imprisoned in several German-run concentration camps from 1941-1945. They were originally from Prague which was annexed by Nazi Germany in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents, Jindrich and Irma, siblings, Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were sent to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp. Karel worked in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. Karel was then force marched to Auschwitz III - Monowitz (Buna) concentration camp where he painted prisoner numbers on uniforms. In early 1945, he was transferred to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen, where he was liberated on April 15. Hana and her then husband Rudolf Schiff were sent to Theresienstadt in August 1942. Hana was deported to Auschwitz in October 1944, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp where she was freed in May 1945. Hana and Karel returned to Prague and met while searching for relatives, but most had perished. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

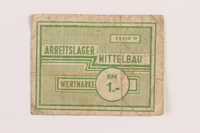

Mittelbau forced labor camp scrip, 1 Reichsmark, issued to a Czech Jewish prisoner

Object

Mittelbau labor camp token, value 1 mark, issued to Karel Bruml while an inmate at Dora-Mittelbau / Nordhausen concentration camp in spring 1945. The coupons could sometimes be exchanged for food rations. Non-Jews could use them for brothel visits. Karel was from Prague which was annexed by Germany in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents, Jindrich and Irma, his siblings, Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were transported to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp. Karel was assigned to work in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. Karel was then force marched to Buna. He moved building materials until reassigned. In early 1945, Karel was transferred to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen concentration camps. On April 15, Bergen-Belsen was liberated by British soldiers. Karel returned to Prague after the war ended in early May. He learned that most of his family had perished. He met Hana Schiff Suk, who had survived Theresienstadt, Auschwitz, and Kudowa-Sackisch. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

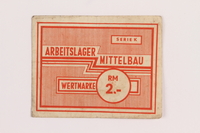

Mittelbau forced labor camp scrip, 2 Reichsmark, issued to a Czech Jewish prisoner

Object

Mittelbau labor camp token, value 2 mark, issued to Karel Bruml while an inmate at Dora-Mittelbau / Nordhausen concentration camp in spring 1945. The coupons could sometimes be exchanged for food rations. Non-Jews could use them for brothel visits.Karel was from Prague which was annexed by Germany in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents, Jindrich and Irma, his siblings, Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were transported to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp. Karel was assigned to work in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. Karel was then force marched to Buna. He moved building materials until reassigned. In early 1945, Karel was transferred to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen concentration camps. On April 15, Bergen-Belsen was liberated by British soldiers. Karel returned to Prague after the war ended in early May. He learned that most of his family had perished. He met Hana Schiff Suk, who had survived Theresienstadt, Auschwitz, and Kudowa-Sackisch. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

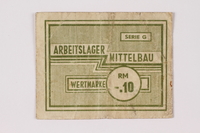

Mittelbau forced labor camp scrip, .10 Reichsmark, issued to a Czech Jewish prisoner

Object

Mittelbau labor camp token, value .10 mark, issued to Karel Bruml while an inmate at Dora-Mittelbau / Nordhausen concentration camp in spring 1945. The coupons could sometimes be exchanged for food rations. Non-Jews could use them for brothel visits.Karel was from Prague which was annexed by Germany in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents, Jindrich and Irma, his siblings, Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were transported to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp. Karel was assigned to work in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. Karel was then force marched to Buna. He moved building materials until reassigned. In early 1945, Karel was transferred to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen concentration camps. On April 15, Bergen-Belsen was liberated by British soldiers. Karel returned to Prague after the war ended in early May. He learned that most of his family had perished. He met Hana Schiff Suk, who had survived Theresienstadt, Auschwitz, and Kudowa-Sackisch. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

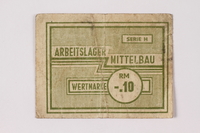

Mittelbau forced labor camp scrip, .10 Reichsmark, issued to a Czech Jewish prisoner

Object

Mittelbau labor camp token, value .10 mark, issued to Karel Bruml while an inmate at Dora-Mittelbau / Nordhausen concentration camp in spring 1945. The coupons could sometimes be exchanged for food rations. Non-Jews could use them for brothel visits. Karel was from Prague which was annexed by Germany in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents, Jindrich and Irma, his siblings, Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were transported to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp. Karel was assigned to work in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. Karel was then force marched to Buna. He moved building materials until reassigned. In early 1945, Karel was transferred to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen concentration camps. On April 15, Bergen-Belsen was liberated by British soldiers. Karel returned to Prague after the war ended in early May. He learned that most of his family had perished. He met Hana Schiff Suk, who had survived Theresienstadt, Auschwitz, and Kudowa-Sackisch. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Mittelbau forced labor camp scrip, .10 Reichsmark, issued to a Czech Jewish prisoner

Object

Mittelbau labor camp token, value .10 mark, issued to Karel Bruml while an inmate at Dora-Mittelbau / Nordhausen concentration camp in spring 1945. The coupons could sometimes be exchanged for food rations. Non-Jews could use them for brothel visits. Karel was from Prague which was annexed by Germany in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents, Jindrich and Irma, his siblings, Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were transported to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp. Karel was assigned to work in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. Karel was then force marched to Buna. He moved building materials until reassigned. In early 1945, Karel was transferred to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen concentration camps. On April 15, Bergen-Belsen was liberated by British soldiers. Karel returned to Prague after the war ended in early May. He learned that most of his family had perished. He met Hana Schiff Suk, who had survived Theresienstadt, Auschwitz, and Kudowa-Sackisch. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Mittelbau forced labor camp scrip, .10 Reichsmark, issued to a Czech Jewish prisoner

Object

Mittelbau labor camp token, value .10 mark, issued to Karel Bruml while an inmate at Dora-Mittelbau / Nordhausen concentration camp in spring 1945. The coupons could sometimes be exchanged for food rations. Non-Jews could use them for brothel visits. Karel was from Prague which was annexed by Germany in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents, Jindrich and Irma, his siblings, Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were transported to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp. Karel was assigned to work in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. Karel was then force marched to Buna. He moved building materials until reassigned. In early 1945, Karel was transferred to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen concentration camps. On April 15, Bergen-Belsen was liberated by British soldiers. Karel returned to Prague after the war ended in early May. He learned that most of his family had perished. He met Hana Schiff Suk, who had survived Theresienstadt, Auschwitz, and Kudowa-Sackisch. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Mittelbau forced labor camp scrip, .25 Reichsmark, issued to a Czech Jewish prisoner

Object

Mittelbau labor camp token, value .25 mark, issued to Karel Bruml while an inmate at Dora-Mittelbau / Nordhausen concentration camp in spring 1945. The coupons could sometimes be exchanged for food rations. Non-Jews could use them for brothel visits. Karel was from Prague which was annexed by Germany in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents, Jindrich and Irma, his siblings, Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were transported to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp. Karel was assigned to work in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. Karel was then force marched to Buna. He moved building materials until reassigned. In early 1945, Karel was transferred to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen concentration camps. On April 15, Bergen-Belsen was liberated by British soldiers. Karel returned to Prague after the war ended in early May. He learned that most of his family had perished. He met Hana Schiff Suk, who had survived Theresienstadt, Auschwitz, and Kudowa-Sackisch. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Mittelbau forced labor camp scrip, .25 Reichsmark, issued to a Czech Jewish prisoner

Object

Mittelbau labor camp token, value .25 mark, issued to Karel Bruml while an inmate at Dora-Mittelbau / Nordhausen concentration camp in spring 1945. The coupons could sometimes be exchanged for food rations. Non-Jews could use them for brothel visits. Karel was from Prague which was annexed by Germany in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents, Jindrich and Irma, his siblings, Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were transported to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp. Karel was assigned to work in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. Karel was then force marched to Buna. He moved building materials until reassigned. In early 1945, Karel was transferred to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen concentration camps. On April 15, Bergen-Belsen was liberated by British soldiers. Karel returned to Prague after the war ended in early May. He learned that most of his family had perished. He met Hana Schiff Suk, who had survived Theresienstadt, Auschwitz, and Kudowa-Sackisch. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Star of David badge with Jude owned by Czech Jewish concentration camp prisoners

Object

Star of David badge printed with Jude, German for Jew, owned by Charles (Karel) and Hana Bruml. This badge may have been worn by one of them. It is the type they would have been required to wear beginning September 1941 in German occupied Prague. Nazi Germany annexed Prague in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents, Jindrich and Irma, siblings, Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were sent to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp. Karel worked in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. Karel was then force marched to Auschwitz III - Monowitz (Buna) concentration camp. In early 1945, he was transferred to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen, where he was liberated on April 15. Hana and her then husband Rudolf Schiff were sent to Theresienstadt in August 1942. Rudolf, his parents, and his brother were deported to Auschwitz in December 1943 and killed. Hana was deported to Auschwitz in October 1944, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp where she was freed in May 1945. Hana and Karel returned to Prague where they met while searching for relatives. They found few survivors. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Star of David badge with Jude owned by Czech Jewish concentration camp prisoners

Object

Star of David badge printed with Jude, German for Jew, owned by Charles (Karel) and Hana Bruml. This badge may have been worn by one of them. It is the type they would have been required to wear beginning September 1941 in German occupied Prague. Nazi Germany annexed Prague in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents, Jindrich and Irma, siblings, Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were sent to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp. Karel worked in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. Karel was then force marched to Auschwitz III - Monowitz (Buna) concentration camp. In early 1945, he was transferred to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen, where he was liberated on April 15. Hana and her then husband Rudolf Schiff were sent to Theresienstadt in August 1942. Rudolf, his parents, and his brother were deported to Auschwitz in December 1943 and killed. Hana was deported to Auschwitz in October 1944, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp where she was freed in May 1945. Hana and Karel returned to Prague where they met while searching for relatives. They found few survivors. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Metal bathroom pass issued to a Jewish Czech slave laborer

Object

Triangular metal badge engraved VDM 88 issued to Hana Schiff from October 1944-May 1945 at the Vereinigte Deutsche Metallwerke [United German Metalworks], Kudowa-Sakisch slave labor camp in Germany. Hana worked 12 hour shifts and was issued 2 lavatory passes daily, which had to be submitted to a female guard each time she used the bathroom. Hana was from Prague which was annexed by Nazi Germany in March 1939. Hana, 20, and her then husband Rudolf Schiff were sent to Thersienstadt ghetto-labor camp in August 1942. Hana was deported to Auschwitz in October 1944, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch where she was freed in May 1945. Hana returned to Prague. While searching for relatives, she met Karel Bruml. They both lost most of their extended families. Hana and Charles left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Man’s dark blue pajama shirt given to a Czech Jewish inmate of Theresienstadt by another inmate

Object

Blue pajama top given by Hana Mueller Schiff (later Bruml) to her cousin Jiri Lauscher when both were prisoners at Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp. The shirt originally belonged to Hana’s husband, Rudolf, who used it in Theresienstadt until he was deported in 1943. The transport number of Jiri's daughter CK 539 is written in the collar. All were sent to the camp from German occupied Prague. Rudolf, 23, and Hana, 21, were transported in August 1942. Rudolf was ill and not assigned to work. Hana was a nurse. Rudolf was deported to Auschwitz with parents Richard and Marta and brother Karel in December 1943, and killed. Hana was deported to Auschwitz in October 1944, and then transferred to Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp. She was freed on May 5, 1945. Jiri, wife Irma, and Michaela, 5, arrived at Terezin in December 1942. Jiri worked in the camp technical department and Irma was a teacher in the clandestine children’s classes. In early May 1945, the camp was liberated. Jiri and his family returned to Prague, as did Hana. They learned that most of their extended families had perished. Hana met Karel Bruml, a former inmate of Terezin, Auschwitz, and several other camps, and both left for America in 1946.

Woman’s lab coat owned by a Czech Jewish inmate while a nurse in Theresienstadt

Object

White, now stained, lab coat used by Hana Mueller Schiff, while a prisoner in Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp where she was a nurse in the infectious disease hospital ward from August 1942 - October 1944. In March 1939, Nazi Germany annexed Prague. Hana, 21, and her husband Rudolf Schiff, 23, were transported on August 10. Hana’s parents were deported to Treblinka killing center in October 1942. Her husband, his parents Richard and Marta, and brother Karel were sent to Auschwitz and killed in December 1943. On October 1, 1944, Hana was deported to Auschwitz, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp in Poland where she worked in an airplane factory. She was liberated on May 5, 1945, and returned to Prague. While searching for surviving family members, Hana met Karel Bruml. He had survived Terezin, Auschwitz, Auschwitz III-Monowitz (Buna) and death marches to Gleiwitz, Dora-Mittelbau, and Bergen-Belsen, where he was liberated on April 15. Hana and Karel found few survivors. They left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Star of David badge on floral backing printed Jude owned by a Czech Jewish survivor

Object

Star of David badge, printed with Jude, German for Jew, owned by Hana Bruml. It appears used and this badge may have been worn by Hana or her husband Charles, but its history is not known. Jews in Prague, which was annexed by Germany in March 1939, were required to wear Judenstern beginning in September 1941. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents Jindrich and Irma, siblings Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were sent to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp. Karel worked in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. His family was killed, but Karel was sent to Auschwitz III - Monowitz (Buna). In early 1945, he was sent to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen, where he was liberated on April 15. Hana and her then husband Rudolf Schiff were sent to Theresienstadt in August 1942. Rudolf, his parents, and brother were deported to Auschwitz in December 1943 and killed. Hana was deported to Auschwitz in October 1944, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp where she was freed in May 1945. Hana and Karel returned to Prague where they met while searching for relatives. They found few survivors. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Star of David badge printed Jude owned by a Czech Jewish survivor

Object

Unused Star of David badge, printed with Jude, German for Jew, owned by Hana Bruml. This badge appears unused but it is the type that Hana or Charles Bruml would have required in Prague beginning in September 1941. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents Jindrich and Irma, siblings Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were sent to Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp. Karel worked in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. His family was killed, but Karel was sent to Auschwitz III - Monowitz (Buna). In early 1945, he was sent to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen, where he was liberated on April 15. Hana and her then husband Rudolf Schiff were sent to Theresienstadt in August 1942. Rudolf, his parents, and brother were deported to Auschwitz in December 1943 and killed. Hana was deported to Auschwitz in October 1944, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp where she was freed in May 1945. Hana and Karel returned to Prague where they met while searching for relatives. They found few survivors. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Postwar sketch of inmates in a food line inscribed to a Czech Jewish survivor

Object

Pencil drawing given to Hana Mueller Schiff Sukova in postwar Prague, April 1946, not long before she left for the United States. It is a sketch of people waiting in line with pails for food rations in a courtyard resembling Theresienstadt, with an inscription suggesting the artist and Hana were both prisoners there. In March 1939, Prague was annexed by Nazi Germany. Hana, 21, and her husband Rudolf Schiff, 23, were sent on August 10. Hana’s parents were deported to Treblinka killing center in October 1942. Her husband, his parents Richard and Marta, and brother Karel, were sent to Auschwitz and killed in December 1943. On October 1, 1944, Hana was deported to Auschwitz, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp in Poland where she was freed on May 5, 1945. She returned to Prague and while searching for surviving family members met Karel Bruml. He had survived Terezin, Auschwitz, Auschwitz III-Monowitz (Buna) and death marches to Gleiwitz, Dora-Mittelbau, and Bergen-Belsen, where he was liberated on April 15. Hana and Karel found few surviving relatives. They left separately for America in 1946, where they married.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 1 krone, owned by a former Czech Jewish inmate

Object

Theresienstadt scrip, 1 (eine) krone, owned by Charles (Karel) and Hana Bruml, who were prisoners at the ghetto-labor camp. This type of scrip was produced at the camp beginning in spring 1943. Currency was confiscated from incoming inmates and replaced with scrip. It was also provided to pensioners and to camp workers as payment. There was nothing to exchange it for in the camp, except library books. Germany annexed Prague in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents Jindrich and Irma, siblings Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were sent to Theresienstadt. Karel worked in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. His family was killed, but Karel was force marched to Auschwitz III - Monowitz (Buna) concentration camp. In early 1945, he was transferred to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen, where he was liberated on April 15. Hana and her husband Rudolf Schiff were sent to Theresienstadt in August 1942. Rudolf, his parents, and his brother were deported to Auschwitz in December 1943 and killed. Hana was deported to Auschwitz in October 1944, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp where she was freed in May 1945. Hana and Karel returned to Prague where they met while searching for relatives. They found few survivors. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 1 kronen, owned by a former Czech Jewish inmate

Object

Theresienstadt scrip, 1 (eine) kronen, owned by Charles (Karel) and Hana Bruml, who were prisoners at the ghetto-labor camp. This type of scrip was produced at the camp beginning in spring 1943. Currency was confiscated from incoming inmates and replaced with scrip. It was also provided to pensioners and to camp workers as payment. There was nothing to exchange it for in the camp, except library books. Germany annexed Prague in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents Jindrich and Irma, siblings Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were sent to Theresienstadt. Karel worked in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. His family was killed, but Karel was force marched to Auschwitz III - Monowitz (Buna) concentration camp. In early 1945, he was transferred to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen, where he was liberated on April 15. Hana and her husband Rudolf Schiff were sent to Theresienstadt in August 1942. Rudolf, his parents, and his brother were deported to Auschwitz in December 1943 and killed. Hana was deported to Auschwitz in October 1944, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp where she was freed in May 1945. Hana and Karel returned to Prague where they met while searching for relatives. They found few survivors. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 1 krone, owned by a former Czech Jewish inmate

Object

Theresienstadt scrip, 1 (eine) krone, owned by Charles (Karel) and Hana Bruml, who were prisoners at the ghetto-labor camp. This type of scrip was produced at the camp beginning in spring 1943. Currency was confiscated from incoming inmates and replaced with scrip. It was also provided to pensioners and to camp workers as payment. There was nothing to exchange it for in the camp, except library books. Germany annexed Prague in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents Jindrich and Irma, siblings Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were sent to Theresienstadt. Karel worked in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. His family was killed, but Karel was force marched to Auschwitz III - Monowitz (Buna) concentration camp. In early 1945, he was transferred to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen, where he was liberated on April 15. Hana and her husband Rudolf Schiff were sent to Theresienstadt in August 1942. Rudolf, his parents, and his brother were deported to Auschwitz in December 1943 and killed. Hana was deported to Auschwitz in October 1944, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp where she was freed in May 1945. Hana and Karel returned to Prague where they met while searching for relatives. They found few survivors. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 1 krone, owned by a former Czech Jewish inmate

Object

Theresienstadt scrip, 1 (eine) krone, owned by Charles (Karel) and Hana Bruml, who were prisoners at the ghetto-labor camp. This type of scrip was produced at the camp beginning in spring 1943. Currency was confiscated from incoming inmates and replaced with scrip. It was also provided to pensioners and to camp workers as payment. There was nothing to exchange it for in the camp, except library books. Germany annexed Prague in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents Jindrich and Irma, siblings Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were sent to Theresienstadt. Karel worked in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. His family was killed, but Karel was force marched to Auschwitz III - Monowitz (Buna) concentration camp. In early 1945, he was transferred to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen, where he was liberated on April 15. Hana and her husband Rudolf Schiff were sent to Theresienstadt in August 1942. Rudolf, his parents, and his brother were deported to Auschwitz in December 1943 and killed. Hana was deported to Auschwitz in October 1944, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp where she was freed in May 1945. Hana and Karel returned to Prague where they met while searching for relatives. They found few survivors. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 1 krone, owned by a former Czech Jewish inmate

Object

Theresienstadt scrip, 1 (eine) krone, owned by Charles (Karel) and Hana Bruml, who were prisoners at the ghetto-labor camp. This type of scrip was produced at the camp beginning in spring 1943. Currency was confiscated from incoming inmates and replaced with scrip. It was also provided to pensioners and to camp workers as payment. There was nothing to exchange it for in the camp, except library books. Germany annexed Prague in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents Jindrich and Irma, siblings Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were sent to Theresienstadt. Karel worked in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. His family was killed, but Karel was force marched to Auschwitz III - Monowitz (Buna) concentration camp. In early 1945, he was transferred to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen, where he was liberated on April 15. Hana and her husband Rudolf Schiff were sent to Theresienstadt in August 1942. Rudolf, his parents, and his brother were deported to Auschwitz in December 1943 and killed. Hana was deported to Auschwitz in October 1944, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp where she was freed in May 1945. Hana and Karel returned to Prague where they met while searching for relatives. They found few survivors. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 2 kronen, owned by a former Czech Jewish inmate

Object

Theresienstadt scrip, 2 (zwei) kronen, owned by Charles (Karel) and Hana Bruml, who were prisoners at the ghetto-labor camp. This type of scrip was produced at the camp beginning in spring 1943. Currency was confiscated from incoming inmates and replaced with scrip. It was also provided to pensioners and to camp workers as payment. There was nothing to exchange it for in the camp, except library books. Germany annexed Prague in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents Jindrich and Irma, siblings Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were sent to Theresienstadt. Karel worked in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. His family was killed, but Karel was force marched to Auschwitz III - Monowitz (Buna) concentration camp. In early 1945, he was transferred to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen, where he was liberated on April 15. Hana and her husband Rudolf Schiff were sent to Theresienstadt in August 1942. Rudolf, his parents, and his brother were deported to Auschwitz in December 1943 and killed. Hana was deported to Auschwitz in October 1944, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp where she was freed in May 1945. Hana and Karel returned to Prague where they met while searching for relatives. They found few survivors. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 2 kronen, owned by a former Czech Jewish inmate

Object

Theresienstadt scrip, 2 (zwei) kronen, owned by Charles (Karel) and Hana Bruml, who were prisoners at the ghetto-labor camp. This type of scrip was produced at the camp beginning in spring 1943. Currency was confiscated from incoming inmates and replaced with scrip. It was also provided to pensioners and to camp workers as payment. There was nothing to exchange it for in the camp, except library books. Germany annexed Prague in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents Jindrich and Irma, siblings Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were sent to Theresienstadt. Karel worked in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. His family was killed, but Karel was force marched to Auschwitz III - Monowitz (Buna) concentration camp. In early 1945, he was transferred to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen, where he was liberated on April 15. Hana and her husband Rudolf Schiff were sent to Theresienstadt in August 1942. Rudolf, his parents, and his brother were deported to Auschwitz in December 1943 and killed. Hana was deported to Auschwitz in October 1944, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp where she was freed in May 1945. Hana and Karel returned to Prague where they met while searching for relatives. They found few survivors. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 2 kronen, owned by a former Czech Jewish inmate

Object

Theresienstadt scrip, 2 (zwei) kronen, owned by Charles (Karel) and Hana Bruml, who were prisoners at the ghetto-labor camp. This type of scrip was produced at the camp beginning in spring 1943. Currency was confiscated from incoming inmates and replaced with scrip. It was also provided to pensioners and to camp workers as payment. There was nothing to exchange it for in the camp, except library books. Germany annexed Prague in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents Jindrich and Irma, siblings Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were sent to Theresienstadt. Karel worked in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. His family was killed, but Karel was force marched to Auschwitz III - Monowitz (Buna) concentration camp. In early 1945, he was transferred to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen, where he was liberated on April 15. Hana and her husband Rudolf Schiff were sent to Theresienstadt in August 1942. Rudolf, his parents, and his brother were deported to Auschwitz in December 1943 and killed. Hana was deported to Auschwitz in October 1944, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp where she was freed in May 1945. Hana and Karel returned to Prague where they met while searching for relatives. They found few survivors. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 2 kronen, owned by a former Czech Jewish inmate

Object

Theresienstadt scrip, 2 (zwei) kronen, owned by Charles (Karel) and Hana Bruml, who were prisoners at the ghetto-labor camp. This type of scrip was produced at the camp beginning in spring 1943. Currency was confiscated from incoming inmates and replaced with scrip. It was also provided to pensioners and to camp workers as payment. There was nothing to exchange it for in the camp, except library books. Germany annexed Prague in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents Jindrich and Irma, siblings Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were sent to Theresienstadt. Karel worked in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. His family was killed, but Karel was force marched to Auschwitz III - Monowitz (Buna) concentration camp. In early 1945, he was transferred to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen, where he was liberated on April 15. Hana and her husband Rudolf Schiff were sent to Theresienstadt in August 1942. Rudolf, his parents, and his brother were deported to Auschwitz in December 1943 and killed. Hana was deported to Auschwitz in October 1944, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp where she was freed in May 1945. Hana and Karel returned to Prague where they met while searching for relatives. They found few survivors. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 2 kronen, owned by a former Czech Jewish inmate

Object

Theresienstadt scrip, 2 (zwei) kronen, owned by Charles (Karel) and Hana Bruml, who were prisoners at the ghetto-labor camp. This type of scrip was produced at the camp beginning in spring 1943. Currency was confiscated from incoming inmates and replaced with scrip. It was also provided to pensioners and to camp workers as payment. There was nothing to exchange it for in the camp, except library books. Germany annexed Prague in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents Jindrich and Irma, siblings Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were sent to Theresienstadt. Karel worked in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. His family was killed, but Karel was force marched to Auschwitz III - Monowitz (Buna) concentration camp. In early 1945, he was transferred to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen, where he was liberated on April 15. Hana and her husband Rudolf Schiff were sent to Theresienstadt in August 1942. Rudolf, his parents, and his brother were deported to Auschwitz in December 1943 and killed. Hana was deported to Auschwitz in October 1944, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp where she was freed in May 1945. Hana and Karel returned to Prague where they met while searching for relatives. They found few survivors. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

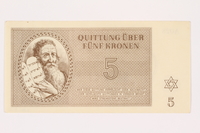

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 5 kronen, owned by a former Czech Jewish inmate

Object

Theresienstadt scrip, 5 (funf) kronen, owned by Charles (Karel) and Hana Bruml, who were prisoners at the ghetto-labor camp. This type of scrip was produced at the camp beginning in spring 1943. Currency was confiscated from incoming inmates and replaced with scrip. It was also provided to pensioners and to camp workers as payment. There was nothing to exchange it for in the camp, except library books. Germany annexed Prague in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents Jindrich and Irma, siblings Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were sent to Theresienstadt. Karel worked in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. His family was killed, but Karel was force marched to Auschwitz III - Monowitz (Buna) concentration camp. In early 1945, he was transferred to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen, where he was liberated on April 15. Hana and her husband Rudolf Schiff were sent to Theresienstadt in August 1942. Rudolf, his parents, and his brother were deported to Auschwitz in December 1943 and killed. Hana was deported to Auschwitz in October 1944, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp where she was freed in May 1945. Hana and Karel returned to Prague where they met while searching for relatives. They found few survivors. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 5 kronen, owned by a former Czech Jewish inmate

Object

Theresienstadt scrip, 5 (funf) kronen, owned by Charles (Karel) and Hana Bruml, who were prisoners at the ghetto-labor camp. This type of scrip was produced at the camp beginning in spring 1943. Currency was confiscated from incoming inmates and replaced with scrip. It was also provided to pensioners and to camp workers as payment. There was nothing to exchange it for in the camp, except library books. Germany annexed Prague in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents Jindrich and Irma, siblings Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were sent to Theresienstadt. Karel worked in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. His family was killed, but Karel was force marched to Auschwitz III - Monowitz (Buna) concentration camp. In early 1945, he was transferred to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen, where he was liberated on April 15. Hana and her husband Rudolf Schiff were sent to Theresienstadt in August 1942. Rudolf, his parents, and his brother were deported to Auschwitz in December 1943 and killed. Hana was deported to Auschwitz in October 1944, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp where she was freed in May 1945. Hana and Karel returned to Prague where they met while searching for relatives. They found few survivors. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.

Theresienstadt ghetto-labor camp scrip, 5 kronen, owned by a former Czech Jewish inmate

Object

Theresienstadt scrip, 5 (funf) kronen, owned by Charles (Karel) and Hana Bruml, who were prisoners at the ghetto-labor camp. This type of scrip was produced at the camp beginning in spring 1943. Currency was confiscated from incoming inmates and replaced with scrip. It was also provided to pensioners and to camp workers as payment. There was nothing to exchange it for in the camp, except library books. Germany annexed Prague in March 1939. On December 10, 1941, Karel, his parents Jindrich and Irma, siblings Anna and Otto, and Otto’s wife Irma were sent to Theresienstadt. Karel worked in the technical department. On October 26, 1942, Karel’s parents and sister were selected for deportation and Karel volunteered to go with them. They were sent to Auschwitz. His family was killed, but Karel was force marched to Auschwitz III - Monowitz (Buna) concentration camp. In early 1945, he was transferred to Gleiwitz, Nordhausen, and Bergen-Belsen, where he was liberated on April 15. Hana and her husband Rudolf Schiff were sent to Theresienstadt in August 1942. Rudolf, his parents, and his brother were deported to Auschwitz in December 1943 and killed. Hana was deported to Auschwitz in October 1944, and then sent to Kudowa-Sackisch slave labor camp where she was freed in May 1945. Hana and Karel returned to Prague where they met while searching for relatives. They found few survivors. They both left for the United States in 1946, where they married.