Overview

- Description

- Jan Karski tells of his capture and torture by the Gestapo when he was a courier for the Polish underground. He also describes his clandestine visit to the Warsaw ghetto and his meeting with Szmul Zygielbojm, six months before Zygelbojm's suicide. See pages 491 - 494 of the English translation of Lanzmann's memoir The Patagonian Hare (March 2012) for a description of his interactions with Karski after filming this interview.

FILM ID 3133 -- Camera Rolls #1-5 -- 01:00:33 to 01:32:10

Karski tells of his first missions as a courier for the Polish Government in Exile. [No visual until 01:01:56] He was caught by the SS with an incriminating roll of film and beaten severely. The SS soldier told him that he wanted to get in touch with the Polish underground, but Karski did not reveal any information to him. Karski cut both of his wrists and was transported to various hospitals under the supervision of the Gestapo. With help, Karski escaped from a hospital in Warsaw and after a period of recuperation went to Krakow in 1940. In 1942, he resumed his service as a courier and met with major political parties to deliver messages from the delegates of the Polish Government. He explains that the messages were never written down, but were either memorized or on microfilm. Karski was contacted by representatives of the Jewish underground, who he refers to as the Bund leader (Leon Feiner) and the Zionist leader (Bermann), and met with them in a house near but not in the ghetto. In a manner that Karski describes as desperate, the two leaders asked Karski to take messages to London about the extermination of the Jews. Karski was asked to tell the exiled Polish president to contact the Pope. He was also told not to contact non-Polish Jewish leaders in London because they might become too alarmed and "complicate" matters.

FILM ID 3134 -- Camera Rolls #7-9 -- 02:00:05 to 02:35:47

The Jewish leaders wanted Karski to go to other government officials with messages. They wanted the Allied governments to publicly announce that they would deal with the problem of the extermination of the Jews and to drop leaflets over the German population, telling them that the Germans would be held responsible. Karski was also asked to take messages to certain Jewish members of the exiled Polish government, including Szmul Zygielbojm and Dr. Schwarzbald of the National Council and Dr. Leon Grossfeld of the Polish Socialist Party. The two representatives made it clear that he was not to relay the message to any non-Polish Jewish leader because they feared that it would fuel anti-Polish propaganda. Karski discusses the frustration of Feiner and Bermann that the Home Army refused to supply Polish Jews with weapons. Lanzmann and Karski discuss whether this proves that these two representatives anticipated the Warsaw ghetto uprising.

FILM ID 3135 -- Camera Rolls #11,12,6,11A,32 -- 03:00:04 to 03:07:48

Lanzmann asks Karski how his visit to the ghetto came about. Karski says that it was the Bund leader's idea that if Karski saw the situation with his own eyes, it would strengthen his position when he went to London. Karski says that he and Feiner had no problem entering the ghetto through a tunnel. A brief shot of Karski's wife and then a long shot of Lanzmann with no sound.

FILM ID 3136 -- Camera Rolls #13-15 -- 04:00:09 to 04:33:01

In November 1942, Karski visited Belzec disguised as an Estonian auxiliary. His trip was organized by the Bund leader and the Jewish underground. Karski describes the brutal treatment of Jews as they were loaded onto trucks, either to be taken to Sobibor or left to die on the trucks. Karski says that at the time, Belzec seemed to function as a transitional camp. [CLIP 1 BEGINS] Lanzmann asks Karski to go into more detail about what he saw at Belzec [CLIP 1 ENDS].

FILM ID 3137 -- Camera Rolls #16-18 -- 05:00:08 to 05:18:45

[CLIP 2 BEGINS] Karski talks about watching Jews being pushed onto the trains at Belzec. He describes what he saw as, "a crowd which had many heads, legs, many arms, many eyes, but it was something like a collective, pulsating, moving, shouting body." Karski and Lanzmann talk about the use of quicklime in the trains again. [CLIP 2 ENDS] No sound from 05:11:20 until 05:14:48. [CLIP 3 BEGINS] Karski left the camp in a state of shock [CLIP 3 ENDS].

FILM ID 3138 -- Camera Rolls #19,19A,20,20A -- 06:00:01 to 06:21:07

Karski talks about his trip to London in late November, focusing on his meeting with Zygielbojm. Zygielbojm was aggressive with Karski and rude to him. Karski felt that the man was "disintegrating minute by minute."

FILM ID 3139 -- Camera Rolls #21,21A,22 -- 07:00:07 to 07:17:16

Karski describes how Zygielbojm went into a rage after he delivered his report to him. Camera focused on Lanzmann, no sound. Lanzmann asks Karski if he thinks his report contributed to Zygielbojm's suicide six months later. Karski says that he believes that the total helplessness of the Jews and the indifference of the world to the Jewish situation contributed to Zygielbojm's death. He says that while he never mentions to his students his own experiences in the Warsaw ghetto and in Belzec, he always tells them about Zygielbojm.

FILM ID 3140 -- Camera Rolls #23-24 -- 08:00:02 to 08:17:34

Lanzmann asks Karski to whom specifically he reported his news about the destruction of the Jews, and what were the reactions. He tells of being sent to Washington from London and of a meeting with Roosevelt. Karski first told Roosevelt that the Polish nation was depending on him to deliver them from the Germans. Karski said to Roosevelt, "All hope, Mr. President, has been placed by the Polish nation in the hands of Franklin Delano Roosevelt."

FILM ID 3141 -- Camera Rolls #25-28 -- 09:00:11 to 09:33:07

Karski says that he told President Roosevelt about Belzec and the desperate situation of the Jews. Roosevelt concentrated his questions and remarks entirely on Poland and did not ask one question about the Jews. Soon after his meeting with the President, Karski received a message from FDR with a list of several people with whom Karski should speak. One of the people that the President recommended was Justice Felix Frankfurter of the Supreme Court, who came to see Karski in the Polish embassy. Frankfurter listened to his report and said that he did not, could not believe Karski's report. Karski was interviewed by Lord Selborne who was in charge of the European underground movement of the British government. Selborne told him that he knew that Karski's story wasn't true, but that it was good for propaganda purposes, just as it was necessary in World War I to use atrocity stories against the Germans.

FILM ID 3142 -- Camera Rolls #29-31 -- 10:00:07 to 10:21:00

Karski talks about his interactions with the other people to whom he reported. Lanzmann asks Karski whether the people he gave his report to in Washington could truly grasp what was happening in places like Belzec. Karski replies that he doesn't think so. Karski says that what happened to the Jews is not comparable to any other event in history.

FILM ID 3143 -- Camera Rolls #33-35,34,36 -- 11:00:07 to 11:12:30

Karski shows Lanzmann a book with clippings of articles written by him or about him. Karski explains that he could no longer work as a courier or return to Poland because he was too recognizable. Instead, he gave lectures and wrote articles and a book about what was happening to the Jews. In spite of this, Karski says, "Hitler won his war." Close up of Karski as he flips through the pages of the scrapbook. - Duration

- 04:13:12

- Date

-

Event:

1978 October

Production: 1985

- Locale

-

Washington, DC,

United States

- Credit

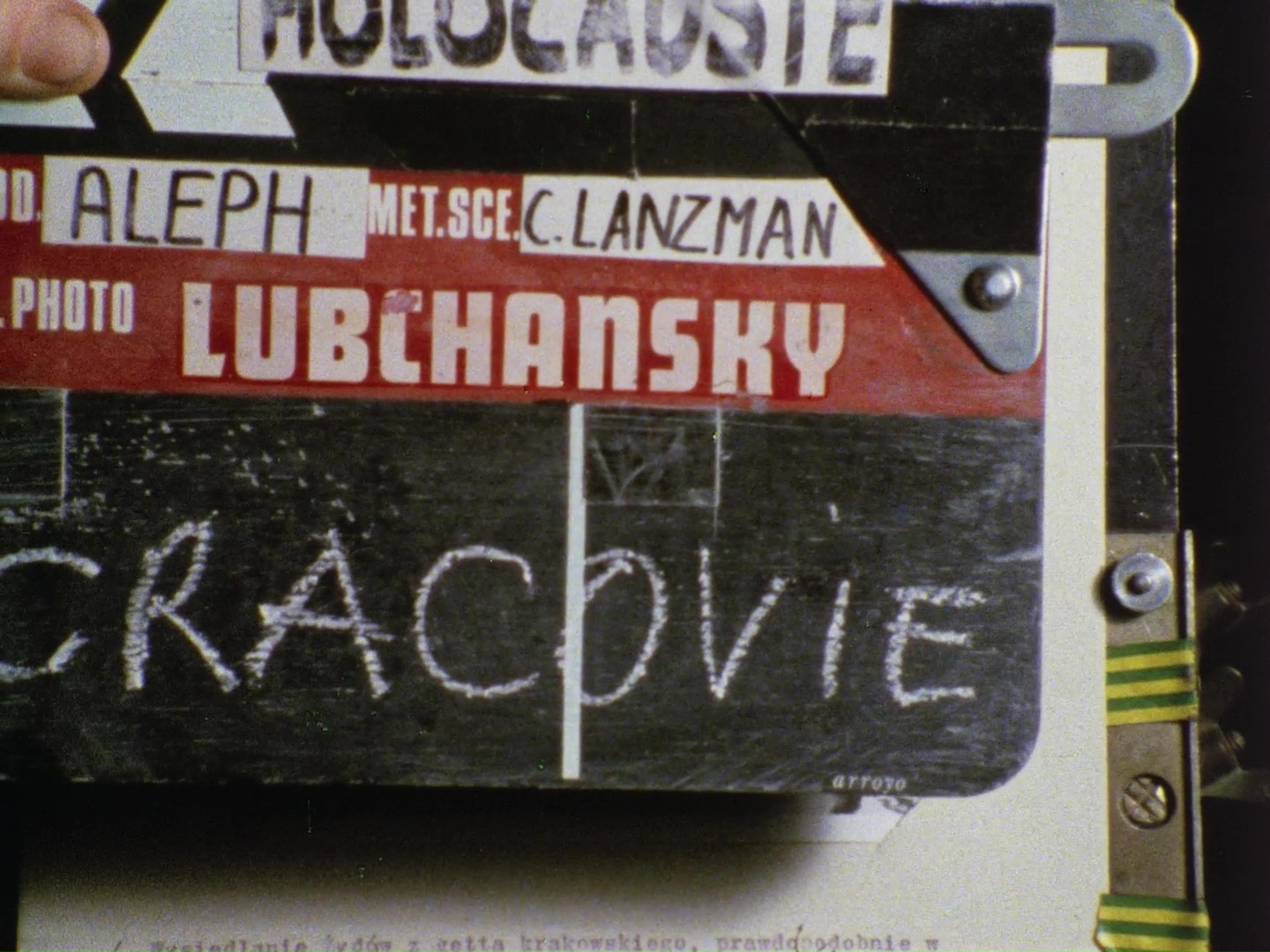

- Created by Claude Lanzmann during the filming of "Shoah," used by permission of USHMM and Yad Vashem

- Contributor

-

Director:

Claude Lanzmann

Subject: Jan Karski

Cinematographer: William Lubtchansky

Cinematographer: Dominique Chapuis

Assistant: Irena Steinfeldt

- Biography

-

Claude Lanzmann was born in Paris to a Jewish family that immigrated to France from Eastern Europe. He attended the Lycée Blaise-Pascal in Clermont-Ferrand. His family went into hiding during World War II. He joined the French resistance at the age of 18 and fought in the Auvergne. Lanzmann opposed the French war in Algeria and signed a 1960 antiwar petition. From 1952 to 1959 he lived with Simone de Beauvoir. In 1963 he married French actress Judith Magre. Later, he married Angelika Schrobsdorff, a German-Jewish writer, and then Dominique Petithory in 1995. He is the father of Angélique Lanzmann, born in 1950, and Félix Lanzmann (1993-2017). Lanzmann's most renowned work, Shoah, is widely regarded as the seminal film on the subject of the Holocaust. He began interviewing survivors, historians, witnesses, and perpetrators in 1973 and finished editing the film in 1985. In 2009, Lanzmann published his memoirs under the title "Le lièvre de Patagonie" (The Patagonian Hare). He was chief editor of the journal "Les Temps Modernes," which was founded by Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, until his death on July 5, 2018. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/postscript/claude-lanzmann-changed-the-history-of-filmmaking-with-shoah

Some women central to the production of "Shoah" (1985) include Hebrew interpreter, Francine Kaufmann; Polish interpreter, Barbra Janicka; Yiddish interpreter, Mrs. Apflebaum; assistant directors, Corinna Coulmas and Irena Steinfeldt; editors, Ziva Postec and Anna Ruiz; and assistant editor, Yael Perlov.

Physical Details

- Language

- English

- Genre/Form

- Outtakes.

- B&W / Color

- Color

- Image Quality

- Good

- Film Format

- Master

Master 3140 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3140 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3140 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3140 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3140 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3140 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3140 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3140 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3140 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3140 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3140 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3140 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3140 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3140 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3140 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3140 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3141 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3141 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3141 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3141 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - large

Master 3141 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3141 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3141 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3141 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - large

Master 3141 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3141 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3141 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3141 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - large

Master 3141 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3141 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3141 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3141 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - large

Master 3142 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3142 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3142 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3142 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3142 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3142 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3142 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3142 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3142 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3142 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3142 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3142 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3142 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3142 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3142 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3142 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3143 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3143 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3143 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3143 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3143 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3143 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3143 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3143 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3143 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3143 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3143 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3143 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3143 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3143 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3143 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3143 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3133 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3133 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3133 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3133 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - large

Master 3133 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3133 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3133 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3133 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - large

Master 3133 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3133 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3133 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3133 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - large

Master 3133 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3133 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3133 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3133 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - large

Master 3134 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3134 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3134 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3134 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - large

Master 3134 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3134 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3134 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3134 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - large

Master 3134 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3134 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3134 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3134 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - large

Master 3134 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3134 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3134 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3134 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - large

Master 3135 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3135 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3135 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3135 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3135 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3135 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3135 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3135 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3135 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3135 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3135 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3135 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3135 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3135 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3135 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3135 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3136 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3136 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3136 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3136 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - large

Master 3136 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3136 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3136 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3136 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - large

Master 3136 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3136 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3136 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3136 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - large

Master 3136 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3136 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3136 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3136 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - large

Master 3137 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3137 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3137 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3137 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3137 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3137 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3137 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3137 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3137 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3137 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3137 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3137 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3137 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3137 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3137 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3137 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3138 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3138 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3138 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3138 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3138 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3138 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3138 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3138 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3138 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3138 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3138 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3138 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3138 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3138 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3138 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3138 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3139 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3139 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3139 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3139 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3139 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3139 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3139 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3139 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3139 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3139 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3139 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3139 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small

Master 3139 Film: negative - 16 mm - color - silent - original negative

Master 3139 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - magnetic - sound - workprint

Master 3139 Film: positive - 16 mm - color - workprint

Master 3139 Video: Digital Betacam - color - NTSC - small- Preservation

Preservation 3141 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3141 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3141 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3141 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3141 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3141 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3141 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3141 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3141 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3141 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3141 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3141 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3141 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3141 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3141 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3141 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3142 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3142 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3142 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3142 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3142 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3142 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3142 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3142 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3142 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3142 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3142 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3142 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3142 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3142 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3142 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3142 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3143 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3143 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3143 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3143 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3143 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3143 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3143 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3143 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3143 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3143 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3143 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3143 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3143 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3143 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3143 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3143 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3133 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3133 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3133 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3133 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3133 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3133 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3133 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3133 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3133 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3133 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3133 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3133 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3133 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3133 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3133 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3133 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3134 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3134 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3134 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3134 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3134 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3134 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3134 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3134 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3134 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3134 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3134 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3134 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3134 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3134 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3134 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3134 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3135 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3135 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3135 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3135 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3135 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3135 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3135 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3135 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3135 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3135 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3135 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3135 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3135 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3135 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3135 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3135 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3136 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3136 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3136 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3136 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3136 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3136 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3136 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3136 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3136 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3136 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3136 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3136 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3136 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3136 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3136 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3136 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3137 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3137 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3137 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3137 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3137 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3137 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3137 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3137 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3137 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3137 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3137 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3137 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3137 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3137 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3137 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3137 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3138 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3138 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3138 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3138 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3138 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3138 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3138 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3138 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3138 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3138 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3138 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3138 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3138 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3138 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3138 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3138 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3139 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3139 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3139 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3139 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3139 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3139 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3139 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3139 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3139 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3139 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3139 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3139 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3139 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3139 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3139 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3139 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3140 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3140 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3140 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3140 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3140 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3140 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3140 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3140 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3140 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3140 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3140 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3140 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Preservation 3140 Film: full-coat mag track - 16 mm - polyester

Preservation 3140 Film: positive - 16 mm - polyester - color - silent - interpositive

Preservation 3140 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - small

Preservation 3140 Video: Betacam SP - color - NTSC - large

Rights & Restrictions

- Conditions on Access

- You do not require further permission from the Museum to access this archival media.

- Copyright

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Yad Vashem, State of Israel

- Conditions on Use

- Third party must sign the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum's SHOAH Outtakes Film License Agreement in order to reproduce and use film footage. Contact filmvideo@ushmm.org

- Copyright Holder

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Yad Vashem

State of Israel

Keywords & Subjects

Administrative Notes

- Legal Status

- Permanent Collection

- Film Provenance

- The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum purchased the Shoah outtakes from Claude Lanzmann on October 11, 1996. The Claude Lanzmann Shoah Collection is now jointly owned by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and Yad Vashem - The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority.

- Note

- Jan Karski is in SHOAH (1985). The parts of his interview in the final release are not available at USHMM.

Claude Lanzmann spent twelve years locating survivors, perpetrators, and eyewitnesses for his nine and a half hour film Shoah released in 1985. Without archival footage, Shoah weaves together extraordinary testimonies to render the step-by-step machinery of the destruction of European Jewry. Critics have called it "a masterpiece" and a "monument against forgetting." The Claude Lanzmann SHOAH Collection consists of roughly 185 hours of interview outtakes and 35 hours of location filming.

Staff-curated clips include:

Clip 1, Film ID 3136, 04:20:57 - 04:31:55

Clip 2, Film ID 3137, 05:00:47 - 05:11:10

Clip 3, Film ID 3137, 05:14:54 - 05:18:13

Clip 4, Film ID 3142, 10:11:09 - 10:14:56

The last ten pages of the transcript are missing from the USHMM files. - Film Source

- Claude Lanzmann

- File Number

- Legacy Database File: 4739

- Record last modified:

- 2024-02-21 07:24:27

- This page:

- https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn1003915

Additional Resources

Time Coded Notes (11)

- Time Coded Notes 1 (English)

- Time Coded Notes 2 (English)

- Time Coded Notes 3 (English)

- Time Coded Notes 4 (English)

- Time Coded Notes 5 (English)

- Time Coded Notes 6 (English)

- Time Coded Notes 7 (English)

- Time Coded Notes 8 (English)

- Time Coded Notes 9 (English)

- Time Coded Notes 10 (English)

- Time Coded Notes 11 (English)

Download & Licensing

- Request Copy

- See Rights and Restrictions

- Terms of Use

- This record is digitized but cannot be downloaded online.

In-Person Research

- Available for Research

- Plan a Research Visit

Contact Us

Also in Claude Lanzmann Shoah Collection

Claude Lanzmann spent twelve years locating and interviewing survivors, perpetrators, eyewitnesses, and scholars for the nine-and-a-half-hour film SHOAH released in 1985. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum purchased the archive of SHOAH outtakes from Mr. Lanzmann on October 11, 1996, and have since been carrying out the painstaking work necessary to reconstruct and preserve the films, which consist of 185 hours of interview outtakes and 35 hours of location filming. The collection is jointly owned by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and Yad Vashem. SHOAH is widely regarded as the seminal film on the subject of the Holocaust. It weaves together extraordinary testimonies to describe the step-by-step machinery implemented to destroy European Jewry. Critics call it “a sheer masterpiece” and a “monument against forgetting.”

Tadeusz Pankiewicz - Cracow

Film

Tadeusz Pankiewicz was a Pole who ran a pharmacy within the confines of the Krakow ghetto, refusing the Germans' offer to let him relocate to another part of the city. He aided Jews by providing free medication and allowing the pharmacy to be used as a meeting place for resisters. FILM ID 3220 -- Camera Rolls #1-2, 3-4, and 5-7 01:00:09 CR 1,2: Lanzmann and Pankiewicz stand in a Krakow street. They spend most of the interview in different parts of the Plac Zgody (now Plac Bohakerow Getta), from which Jews were deported from the Krakow ghetto. They begin walking. Pankiewicz tells Lanzmann that in 1941 he got the order to run a pharmacy within the ghetto. The Germans first required him to prove that he was not Jewish. From the window of his pharmacy he could see all the deportations from Plac Zgody and the horrible treatment meted out to the Jews. Lanzmann asks Pankiewicz to describe exactly what he saw. They are standing on Targowa street, the street where the Jews were gathered for deportation, and where Pankiewics's pharmacy was situated. White screen with some audio from 01:03:16 to 01:04:02. The first slate says "Warsaw" but the interview is clearly in Krakow. CR 2 Lanzmann and Pankiewicz are sitting outdoors on a bench on Plac Lwowska in front of a constuction site (construction of a tram line?). Lanzmann says that an Aryan-run pharmacy in the ghetto was one of a kind. Pankiewicz says that he lived at the Apotheke, because he had to be available day and night. He says that after the liquidation [in March 1943], when the Jews would come from Plaszow, his pharmacy acted as a restaurant, supplying food to them. He talks about the division of the ghetto into two parts, part A (where those still capable of work lived) and part B (where those to be deported lived). He describes the barbed wire surrounding the ghetto and the guarded gates at the edges. Lanzmann asks him to describe the "Grosse Aktion" on the Plac Zgody. Pankiewicz says that Plac Zgody was the main deportation point and that he saw many terrible things from the window of his pharmacy. Lanzmann asks whether the Jews were hopeless and Pankiewicz says they were resigned. He says that when the liquidation came he himself did not eat for three days: he could not go out and he had always eaten in a Jewish restaurant. Pankiewicz says that during the first deportation, in June 1941, the Jews thought that they were being resettled in the Ukraine. However, by the time of the October 28, 1942 deportation the Jews knew that deportation meant death. A woman had written a letter to her relatives, telling them that she was in Belzec. Shots of people walking through the construction site. No audio. 01:16:08. Close-up of sign reading 17 Plac Zgody . Another plaque, perhaps commemorating the location. 02:00:00 CR 3,4: Long shot of the pharmacy. The camera pulls in to reveal Pankiewicz standing outside the pharmacy in a white coat. The pharmacy was located on Targowa Street. Close-ups of Pankiewicz. Shots of Pankiewicz inside the pharmacy. The slate now reads "Krakow." Lanzmann asks Pankiewicz why he wrote a book about his experiences. Pankiewicz says that he wanted to answer the many questions that were put to him after the war, to explain why he was not liquidated himself, and to tell those who had no contact with the ghetto what it was like. A confusing passage about Germans who were arrested immediately after the liquidation of the ghetto and about rescuing some Jews. Pankiewicz talks again about how he sold food, not medicine, to the Jewish laborers from Plaszow, because they were healthy but wanted food. Pankiewicz says that he had Jewish friends even before the war and that he only thinks in terms of good people and bad people, not Jew and non-Jew. He talks about the establishment of the ghetto and his reaction to it (the dates he uses are not consistent). He says he and his family had lived in the location where the ghetto was established, and he talks about hiding Jews in his room during the ghetto's liquidation (or during a deportation?). He says he received a letter from a woman in Israel who claimed to have hidden in the pharmacy, but he did not remember her. Lanzmann asks him about suicide in the ghetto. Pankiewicz says that there were some who did commit suicide, once they knew they were going to be deported. He says that the Jews knew what deportation/evacuation meant and so did he. News and letters came from Belzec. Lanzmann asks him why, in his opinion, if the Jews knew what would happen to them, did they not resist? He says the Jews thought that maybe they would actually survive, that the situation was not as bad as it was in Warsaw. He said many of the Jews had connection to the Polish side and were not as isolated as Warsaw Jews were. He said Jews could leave the ghetto at times but had no place to go. Helping Jews was an automatic death sentence, and the Jews often wanted to take their entire families with them. 03:00:00 CR 5, 6, 7: Pankiewicz knew of several cases where Poles helped Jews after the liquidation of the ghetto, but it was not possible to help entire families. Lanzmann asks Pankiewicz again why he thought the Jews did not fight when they were deported. He says he is not speaking of the Jewish resistance, but of the people who were trapped in the ghetto and deported. Pankiewicz say that the Jews were so resigned, had been through so much terror and horror, that they simply wanted an end. He says that if a wife was deported a husband and children might follow voluntarily. Yet at the same time the Jews maintained some small hope that they might not be murdered, might be able to help each other survive. Lanzmann asks about the role of the Jewish police. He says that there were good and bad police and gives an example of two policemen who he knew in school and who helped him to smuggle a Jew out of Krakow. He talks about various members of the Jewish Council, including Rosenzweig. Lanzmann points out that they were all liquidated in the end. Lanzmann asks again whether his burden was too much to bear during these times. Pankiewicz says no, although he was so bound up with the Jews, that he believed that what happened to them would also happen to him. He says that the Jews have built him up into a kind of legend, but it is not true. He did not know at the time what he was doing, he simply did it. Lanzmann asks him whether he was married at the time and he says no. He says he had dealings with only a few Germans. A new reel begins and Pankiewicz returns to the fact that the Jews have built a small legend out of him, but that he only did what one human should do for other humans who were in a tragic situation. 03:15:02 - 03:17:02 various shots of Pankiewicz.

Claude Lanzmann Shoah Collection

Document

Contains documentation, including indices, summaries, transcripts, and translations, compiled by Claude Lanzmann while developing the film "Shoah."

Abraham Bomba - Treblinka

Film

Abraham Bomba, a barber from Czestochowa, Poland, is featured prominently in the film Shoah. In the outtakes interview he talks about the treatment the Jews received when the Germans first arrived in his town, deportation to Treblinka, and his work cutting the hair of people right before they entered the gas chambers. Bomba escaped from Treblinka and tried to warn the remaining residents of Czestochowa but they did not believe him. In his memoirs published in 2009, Lanzmann calls Bomba "one of the heroes of my film." FILM ID 3197 -- Camera Rolls #1-3A -- 01:00:06 to 01:33:59 Lanzmann asks Bomba how long he has lived in Israel and how he likes it. Bomba says he was a Zionist when he lived in Czestochowa, Poland before the war. He talks about his family, how hard things were after World War I, and the Jewish community of Czestochowa. When the Germans invaded in 1939 his family tried to flee but they had nowhere to go. He describes the rapid stigmatization and loss of rights suffered by the Jews: mandatory armbands, confiscation of radios and valuables, curfews. In 1941 the ghetto was created. Bomba says that conditions were terrible but that people still had hope. He got married in 1940 and in August 1941 (or 1942?) his wife had a son. FILM ID 3198 -- Camera Rolls #4-6 -- 02:00:06 to 02:21:10 On September 22, 1942, the first deportation from Czestochowa took place, and Bomba's brother and his family were deported. Bomba did not know at this time that deportation meant death. Bomba describes the next deportation, when he and his family were selected and loaded onto trains. He says that the Polish people who watched the trains go by laughed at the plight of the Jews. He describes the train journey to Treblinka and arrival at the camp. He was immediately separated from his wife, child, and mother, and assigned to the red (Jewish) commando. FILM ID 3199 -- Camera Rolls #5A,8A,9A -- 03:00:09 to 03:23:23 Camera mostly on Lanzmann with some side views of Bomba. Some segments have no picture. Lanzmann clasps Bomba's hand for most of the interview. Bomba describes arrival at Treblinka and his escape from the camp. Some parts (Camera Rolls 8 and part of 9) are repeated from a different view on Film ID 3200. FILM ID 3200 -- Camera Rolls #7-9 -- 04:00:04 to 04:29:17 [CLIP 1 BEGINS] Bomba was selected to work and he describes the strange quiet that descended after the other prisoners entered the gas chamber, and the location where the corpses were burned. The Germans found out that Bomba was a barber and assigned him to cut the hair of the women before they were gassed. Lanzmann asks Bomba how many people escaped from Treblinka and how he decided to try and escape. Bomba describes his escape from the camp after he had been there for three months [CLIP 1 ENDS]. FILM ID 3201 -- Camera Rolls #10-12 -- 05:00:06 to 05:34:07 [CLIP 2 BEGINS] Bomba and another man manage to return to Czestochowa and tell people there that their relatives who have been sent to Treblinka are dead, but people do not want to believe them. Eventually some of the ghetto residents went to the German commandant, Degenhart [?] and reported Bomba, but Degenhart did not do anything about it [CLIP 2 ENDS]. Lanzmann asks Bomba why he thinks the Jews were so reluctant to believe him about Treblinka. Bomba gives a long answer and says that the Jewish people did not go to the slaughterhouse like sheep, that they did fight back. Bomba talks about the experience of the religious Jews. FILM ID 3202 -- Camera Rolls #13-15 -- 06:00:00 to 06:11:23 This tape contains footage of Bomba in the barber shop. The man in the chair getting his hair cut is Bomba's friend from Czestochowa. There is no dialogue. FILM ID 3203 -- Camera Rolls #16-17 -- 07:00:05 to 07:03:24 Bomba describes the appearance of the gas chamber. He describes cutting the hair of the women and children, who thought that they were about to take showers. FILM ID 3204 -- Camera Rolls #18-19 -- 08:00:06 to 08:32:01 [CLIP 3 BEGINS] Bomba says that the girlfriend of the Jewish commandant, Galewski, arrived at the gas chamber too and he did not tell her what was about to happen. He says the Polish Jews realized more than those from other parts of Europe what was about to happen to them. Bomba tells the story of a woman who managed to cut the throats of two Capos in the gas chamber. One of them died and the Germans gave him a funeral and he was buried, the only proper grave at Treblinka [CLIP 3 ENDS]. Bomba says that the barbers only cut hair in the gas chamber for a short time before they were moved to the undressing barracks. Bomba says it was hard for him to get used to cutting womens' hair again after the war. FILM ID 3205.1 -- Coupes -- 09:00:00 to 09:04:58 Short, mute clips. Boat at sea. Barbershop. FILM ID 3205.2 -- Coupes 14A,20B,19A Short, mute clips. CUS, Bomba sitting outdoors in Israel. CUs, Bomba and Lanzmann during the face to face interview. Beach. Bomba at barber shop.

Andre Steiner

Film

Andre Steiner, an architect, discusses the Judenrat and resistance activities in Slovakia with Lanzmann. He recounts relations with Rabbi Weissmandel and Gisi Fleischmann in their attempt to rescue Slovak Jews from deportation. FILM ID 3414 -- Camera Rolls #1-3 -- 00:00:22 to 00:33:51 CR1 Andre Steiner was born into an assimilated Czechoslovakian Jewish family. He was an architect in Brno and in 1939 he was imprisoned briefly because his father-in-law was a leader of the Jewish Agency in Czechoslovakia. He and his family left Brno for Bratislava as soon as he was released from prison. In Bratislava he eventually became a part of the Judenrat. He was sent out to determine what types of buildings would be needed at the sites where the Germans intended to build concentration camps for the Jews. Steiner, along with Gisi Fleischmann and Dr. Neumann, were convinced that it would be much better for the Jews if they were able to stay in Slovakia, even in camps, rather than be deported to Poland or anywhere else. 00:11:28 CR2 The Slovak government demanded that the work camps be self-supporting within three months. Because of his connections and his position as an architect, Steiner managed to get work with the Slovak government for himself and for other Jewish architects. Steiner says that a few members of the Judenrat, including himself, Gisi Fleischmann, and Dr. Neumann, met separately and made other plans. They did not like the "yes-man" attitude that prevailed among some of the Judenrat members, including the head, Schepersczy?, and Hochberg, who dealt with Dieter Wisliceny, Eichmann's deputy. Lanzmann asks Steiner to elaborate on this "shadow government" formed by the dissident members of the Judenrat. 00:22:40 CR3 Steiner says that Slovakia still had an independent state and the Slovaks were in charge of the deportations. The first deportation happened in spring 1942 when 999 girls were deported. After the deportations started, Rabbi Weissmandel was able to provide them with some news from Poland, and they learned that most of those deported were not going to work camps in Germany, as had been promised, and that families were separated. FILM ID 3415 -- Camera Rolls #4-7 -- 00:00:23 to 00:34:05 CR4 Weissmandel asked Steiner to try and arrange a kosher kitchen in the camps for the orthodox Jews, which Steiner succeeded in doing. Steiner says he began to feel a "magic influence" from Weissmandel and saw what a beautiful person he was on the inside. Weissmandel chose Steiner to be the go-between with Wisliceny, once Hochberg was thrown in jail by the Slovaks. 00:11:36 CR5 Steiner says that there were around 80,000 Jews in Slovakia when the deportations began. 00:12:49 CR6 The deportations from Slovakia quickly became large-scale and Weissmandel convinced Steiner he must bribe both the Slovaks and the Germans, including Wisliceny, to stop the deportations. Steiner tells of his first meeting with Wisliceny, in which he stood up to the German as Weissmandel advised. Steiner invoked "world Jewry" in order to get Wisliceny to believe that he had the money and power to provide a bribe. Lanzmann makes reference to the "Protocols of the Elders of Zion" and the powerful influence that the myth of the Jewish world conspiracy had on the Germans. 00:22:47 CR7 Steiner discusses the source of the bribe money, which provided means of communication between camps and the ability to send medical aid. Steiner confirms that the bribe was successful since no deportations occurred between July and September. In October, three more transports occurred, purportedly due to a false report of the number of Jews in the country, though Weissmandel believed it was because the Jews had not offered more bribe money. After this anomaly, however, deportations ceased completely. FILM ID 3416 -- Camera Rolls #8-14 -- 03:00:08 to 03:33:44 CR8 Weissmandel created a fictitious person named Joseph Rot, based in Switzerland, who represented "world Jewry." 03:00:55 CR9 Steiner and Gisi Fleischmann forged letters from Rot. Steiner says that Weissmandel thought that money would come pouring in to help save the Jews, once it became known what the deportations really meant. In November 1942 Weissmandel burst into Gisi Fleischmann's office, terribly upset, with the first definite news from Poland that deportation meant annihilation. Weissmandel resolved to impart what he had learned of the killings to the world, and wrote to various countries and authorities worldwide. His thinking was that, once the news was known, foreign Jewish money would flow into Eastern Europe to combat the atrocities. 03:11:20 CR10 By bribing Wisliceny they had essentially stopped the deportations from Slovakia (although only 20,000 Jews remained), which encouraged Weissmandel to develop the so-called Europaplan, by which he meant to save the rest of Europe's Jews. Steiner went to Wisliceny and offered two million dollars that they did not have to stop all European deportations. Wisliceny said he had to take the proposition to Himmler, who purportedly said yes to the agreement. Steiner describes Gisi Fleischmann as the person who held the group together. She was a Zionist and very idealistic. 03:22:32 CR11 Steiner speaks of the Europaplan, which was designed to save Jews in France, the Scandinavian countries, and Hungary. Cut early due to telephone ringing. 03:23:34 CR12 Re-take with Steiner discussing the details of the Europaplan. They determined through Weissmandel's "divine arithmetic" that there were around one million Jews left in Europe at this time. 03:24:31 CR13 Re-take with Steiner discussing the Europaplan, fundraising efforts, and negotiations with Wisliceny. Steiner proposed saving 1,000 children who were sent to Theresienstadt from Bialystok, and the failure to raise money to ensure the deal. Solly Meyer, the representative of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee in Switzerland, said he did not believe that the Germans would hold up their end of the bargain. During the Nuremberg trials, Wisliceny stated the reason the children were not saved because the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem objected. 03:30:54 CR14 Lanzmann talks to Steiner about the children's transport to Theresienstadt from Bialystok in winter 1942 and visiting the ghetto with a survivor. FILM ID 3417 -- Camera Rolls #15-17 -- 00:00:23 to 00:34:00 CR15 Lanzmann continues with the story of the children's transport. They were segregated from the rest of the population and given medical care, but after one month they were sent to Auschwitz, where they were gassed upon arrival. Lanzmann confronted Murmelstein about the transport during an earlier interview for the film. This transport has been a mystery that Lanzmann has been trying to solve and now he knows that the children were killed because the money to pay Wisliceny did not come through. Steiner talks about Fleischmann's visit to Hungary. The Hungarian Jews there welcomed her with much pomp and circumstance, a complete contrast from the way the Jews in Slovakia were living. They offered to fundraise and send money, but only through official channels, which was of no use to the Slovak Jews. 00:11:37 CR16 Lanzmann makes a distinction between the aims of the Europaplan, to save all Jews, and the aims of other rescue missions (he mentions Kazstner and Freudiger in Hungary), to pick and choose whom to save. Lanzmann presses Steiner about how he could believe that the Germans, represented by Wisliceny, would have delivered on their end of the Europaplan, if the Slovak Jews had been able to raise the money. Steiner is convinced to this day that the Germans were sincere, and that it was only due to the lack of funds from the "World Jewry" that the plan fell apart. They could not fulfill their side of the deal. 00:22:45 CR17 Even after Wisliceny had left for Greece to organize the deportations of the Greek Jews to Auschwitz, Steiner and company would continue to meet with him during his occasional visits to discuss the plan. Lanzmann asks Steiner what he thinks about the fact that, in September 1944, Weissmandel jumped from a train bound for Auschwitz, leaving his wife and children behind because they refused to come with him. Weissmandel was so disturbed by this series of events that he subsequently considered himself the murderer of his own family. Steiner, however, agrees with what Weissmandel did, and says that while a family could not have escaped in such a fashion, a single person could. The fact that Weissmandel was so integral to the effort to save the European Jews made his survival doubly important. Even though Steiner became quite close with Weissmandel, they never discussed their families. They were concerned with saving unknown multitudes, not their own relatives. FILM ID 3418 -- Camera Rolls #18-19 -- 00:00:23 to 00:21:37 CR18 Lanzmann asks about Rudolf Vrba, who escaped from Auschwitz and whom Lanzmann interviewed. Vrba claims he gave Weissmandel and the others a description of Auschwitz, from which they made a map and distributed it with a request that the Allies bomb the crematoria and the railroad lines. Steiner talks about Weissmandel's suggestion that they blow up a railroad tunnel. Steiner says the Warsaw Ghetto uprising did not change their minds about positively affecting Jewish fates through means other than armed conflict. 00:11:30 CR19 They talk about the end, when the deportations started again in September 1944. Gisi Fleischmann was sent to Auschwitz, where she died. Steiner joined the partisan assisting in the smuggling of weapons into the camps. Steiner says that according to what he has heard, Gisi Fleischmann was singled out to be the first person in the transport to go into the gas chamber as "special treatment" for her role in the Judenrat. Steiner says that the greatest personal satisfaction he ever got was during his time in the "Rettungsaktion," even if only a small segment of the Slovak Jewry was saved by his actions. Steiner continued work as an architect and became a city planner in Atlanta, Georgia after 1950. FILM ID 3419 -- Camera Rolls #20,21,23 -- 06:00:08 to 06:04:03 Silent CUs of Lanzmann. LS, Steiner's home in Atlanta. Steiner exits and walks through his yard. Mute.

Hanna Marton

Film

Hanna Marton is from Cluj (now Romania), formerly the capital of Transylvania. Both Hanna Marton and her husband were lawyers and Zionists. Marton was aboard the train organized by Rudolf (Rezso) Kasztner, carrying 1684 'privileged' Jews that left Hungary for Germany, eventually bringing them to Bergen-Belsen on 9 July 1944. Claude Lanzmann asks questions in French, which Hanna Marton understands, although she replies in Hebrew. Her answers are translated to French by Lanzmann's female translator, Francine Kaufmann. The transcript is in French only. Cluj was also known as Kolozsvar and Klausenburg. Both Lanzmann and Marton use the names Cluj and Kolozsvar interchangebly in the interview. The interview took place over two days in Mrs. Marton's apartment in Jerusalem. FILM ID 3148 -- Camera Rolls #1-5 -- 01:00:00 to 01:29:53 Hanna Marton sits in a chair in front of some bookcases in her home. She holds her husband's diary, a small brown book with the date 1944 embossed on the front, in her lap. Lanzmann clarifies the three names for Cluj: Cluj, Kolozsvar, and Klausenburg. Marton says there were 15,000 Jews in Cluj during the war. She gives some history of the Jewish presence in Cluj, but says that her husband, who died a year and a half ago, knew much more than she does. Both Marton and her husband were Zionists, and she had no contact with the orthodox community. Marton's husband managed to remain working at a high school until June, 1942, when he was sent to the Russian front, returning towards the end of 1943. [CLIP 1 BEGINS] Marton's husband told her that the conditions were terrible, especially during the winter. Lanzmann points out that the Jews were fighting in the Hungarian army, which was in turn fighting with the German army. Marton gives more details about how the Jews were treated by the Hungarians. FILM ID 3149 -- Camera Rolls #6-8 -- 02:00:00 to 02:32:45 Marton received letters from her husband at first but then none came for eight months. The retreat of the Hungarian army was chaotic and the Jews received good treatment from some Russian peasants. Marton says that her husband told her there was an instance where Jews and Wehrmacht soldiers slept together in the same bed in the home of some Russian peasants. [CLIP 2 BEGINS] Of the 60,000 Jews who were sent to the Russian front only 5,000 returned. Marton says that as far as she recalls, in 1942 she did not know about the fate of the Polish Jews, but that she thinks she was aware by 1944, when the Germans took over Hungary. She thinks that most people knew but they didn't want to believe it, and that they followed the orders of the Germans because of a respect for the law. Marton describes how the Jews were ghettoized in Cluj, in May, 1944. They did not receive instructions from the Judenrat and the entire process was conducted by the Hungarians. FILM ID 3150 -- Camera Rolls #9-11 -- 03:00:00 to 03:33:30 The Jews of Cluj were concentrated in a brickyard and slept outside. The first transport left the brickyard within days, and many people volunteered to be on it. Marton had never heard the name Auschwitz at that point. Lanzmann asks Marton about her relationships with the Danzig and Fischer families. Dr. Fischer was Rudolf [Rezso] Kasztner's father-in-law. Marton did not see Kasztner in Cluj. The members of the Judenrat were the last to arrive in the ghetto; they arrived on May 15. [CLIP 3 BEGINS] Marton describes how she first heard from her husband that there was a list of people who would be on a special transport, a transport that would not go to the same destination as the others (the so-called Kasztner Train). She says that she did not want to be part of this special group but her husband convinced her to go. They knew that their fates would be better than that of the Jews who were not on the list. Lanzmann asks Marton what she thought the selection criteria were and says she had no knowledge of a resuce committee in Budapest, that she thought that the list must have been compiled by "our people," the Zionists. Changes were made to the original list for various reasons. Transports were departing regularly and people had realized that the people on these transports would suffer a terrible fate. People made every effort to be a part of the special transport. [CLIP 4 BEGINS] Lanzmann lays out the accusations that have been leveled against Kasztner since the end of the war: that Kasztner chose only his own family and other important people to go on the transport, and that he did not warn the people of Cluj and others that they were destined for extermination. FILM ID 3151 -- Camera Rolls #12-14 -- 04:00:00 to 04:32:39 [CLIP 5 BEGINS] Marton says that perhaps if the people of Cluj had been warned that the deportations meant death then a minority of them would have tried to escape. She says that the Jews simply could not escape the ghetto and that these events were happening all across Europe, not just in Hungary. On June 7th the last transport left Cluj for Auschwitz, so that only the 388 people who were assigned to the special transport remained in the ghetto. Lanzmann asks Marton how they lived with that, how did they look each other in the eye? Marton says that they were in a state of shock, and further that they did not know at the time exactly what awaited them, where they would go, or that it was certain that they would live. Lanzmann and Marton consult Mr. Marton's diary, which provides some detail about who was on the list. Most of those on the list were Zionists. Marton insists that there were some poor people who were part of the group. Marton tells a story about two people from the train who ended up being imprisoned in the Nojverod (??) ghetto. They met Marton's father and were able to assure him that she was on her way to Palestine. Her father said that now he accepted his fate, knowing that she was safe. The transport reached Budapest and they stayed in the Columbus Kasse until June 30th. By the time they left Budapest the transport had swelled to 1684 people. Lanzmann quotes Kasztner about the makeup of the transport and asks Marton how those in the transport were selected, but Marton says she has no idea. She does know, however, that some people refused their places on the transport. One of these people was Jeno Heltai, a Hungarian writer and a couisn of Thedor Herzl. Lanzmann and Marton discuss the composition of the list. FILM ID 3152 -- Camera Roll #15 -- 05:00:00 to 05:10:36 They continue to discuss the makeup of the list. Marton says that Kasztner's use of the the term "Noah's Ark" to describe the transport was correct, and that there were people from all classes on the list. She says that by the time they were travelling on the transport they knew the fate of the rest of the Hungarian Jews at Auschwitz. There was a rumor on the transport that their train was going to Auschwitz. Lanzmann points out that a panic broke out because the passengers confused Auschwitz with another town that they passed through (Auschbitz?). Marton quotes from her husband's diary about this panic. FILM ID 3153 -- Camera Roll #16 -- 06:00:00 to 06:11:27:30 Lanzmann reviews what Marton has told him about two panics that occurred among the members of the Kasztner transport: one when the passengers confused the words Aushbitz (? a town in Czechoslovakia) with Auschwitz, and another panic that occurred in Linz: when the passengers were ordered into showers for disinfection the Polish Jews thought they would be gassed. Marton says that during the journey they did not know where they were being sent. They arrived eventually at Celle and walked to Bergen-Belsen. Marton checks her husband's diary and states the number of people of various age groups who were part of the transport. FILM ID 3154 -- Camera Roll #17 -- 07:00:00 to 07:11:18 [CLIP 6 BEGINS] Marton describes the conditions at Bergen-Belsen. She says that the group was lead by Dr. Fischer and that the Jews participated in holiday observances, lectures, and other activities. She does not remember the Germans entering their barracks and thus they were free to pursue such activities. Dr. Fischer had the contacts with the Germans. The group stayed at Bergen-Belsen from July until December, 1944, although a group of about 300 left for Switzerland in August. FILM ID 3155 -- Camera Rolls #18-19 -- 08:00:00 to 08:21:40 [CLIP 7 BEGINS] Lanzmann asks Marton how those Jews who were on the Kasztner transport could live with themselves, knowing that the other Jews of Cluj were killed, and Marton says that they asked themselves why they were chosen. She says further that one should blame the Nazis for instituting such a system, rather than those who were forced by the Nazis to make the decisions about who would live and who would die. Hermann Krumey, Eichmann's second in command, announced to them that those Jews of Hungarian citizenship would leave for Switzerland first. Marton describes crossing the border from Germany, which was dark and gloomy, into the well-lit territory of Switzerland. They spent their first night in St. Gallen. Marton did not return to Cluj until 1968, having made a vow never to go back there, and she regretted it when she did visit in 1968. Marton still keeps in touch with friends from Cluj. In response to a question from Lanzmann Marton says that she still lives with the guilt of being one of those who survived, although her husband, being a fatalist, did not feel guilty. FILM ID 3156 -- Camera Rolls #20-21 -- 09:00:00 to 09:17:10 Marton knew Kazstner for many years before the Holocaust, and she thinks that the Kazstner trial was one of the most terrible things she has seen since coming to Israel. [CLIP 8 BEGINS] Lanzmann asks her whether she thinks that perhaps Kazstner went too far, and Marton says no. Marton says that in Israel she feels like she can never be hunted down again. Lanzmann asks her why she has had tears in eyes throughout the interview. Marton says it is a problem with her eyes but that sometimes she is crying real tears, especially since the death of her husband. The camera focuses on a portrait of Marton's husband. FILM ID 3157 -- Camera Rolls #5A,1A-B,21A-C,19A,9A-B,13A-C,15A,18A-B -- 10:00:00 to 10:14:03 No audio. Panning shots around Marton's living room, including books and art. Marton looks through her husband's diary. Lanzmann sits across from her while she reads. Shots of Lanzmann as he listens to Marton speak (she is not in the frame). Close-ups of Marton and of the diary.

Hermann Landau

Film

Hermann Landau talks about the rescue work of Rabbi Weissmandel, as well as rescue efforts based in Switzerland and the U.S. He describes Weissmandel as an increasingly desperate man who would not hesitate to bribe the Nazis or commit violence if it would help the Jews. FILM ID 3144 -- Camera Rolls #143-146 Lanzmann asks Landau about his first meeting with Rabbi Weissmandel in Switzerland immediately after the war. Weissmandel was enraged with those who did not do more to help the Jews, including Landau, whom he physically attacked when they met. They discuss how Weissmandel jumped from the train bound for Auschwitz, leaving behind his wife and children. While in Switzerland Weissmandel took an entire bottle of sleeping pills and was in a coma for several days. [CLIP 1 BEGINS] Landau talks about Weissmandel's dealings with Dieter Wisliceny, Adolf Eichmann's deputy. Landau reads from one of Weissmandel's passionate letters about what is happening to the Jews, in which he implores people to send money. They discuss Weissmandel's "Europa Plan." Landau says that they knew, from Weissmandel and from other sources, that the Jews were being exterminated, and that they believed with Weissmandel that money could save some Jews. 01:21 Film clapboard with ident. Roll NY 146. Landau says that at first Weissmandel's approach to rescuing the Jews was nonviolent but that by the end of May 1944, when the Hungarian Jews were being deported, he had changed his mind and wanted the tracks leading to Auschwitz bombed [CLIP 1 ENDS]. Landau mentions that he (Landau) was a member of the Judenrat in Belgium until 1942, when he escaped to Switzerland. He says of course it was wrong for the Judenrat to give lists of Jews to the Germans but that's what they did. [CLIP 2 BEGINS] Landau reads another letter from Weissmandel. FILM ID 3145 -- Camera Rolls #147,148,150,152 Landau explains the meaning of Kiddush Hashem. Lanzmann asks whether any of the recipients of Weissmandel's letters put in the amount of effort that he was requesting toward the rescue of the Jews. Landau says that a couple called the Sternbuchs, who worked for the Vaad Hatzala, worked day and night on rescue efforts, including on the Sabbath. Landau reads some of the strongly-worded cables the Sternbuchs sent to New York. Landau gives some reasons why the American Jews did not give more money to save the European Jews. He says that many of the organizations involved in relief work did not understand that they must use any means necessary [CLIP 2 ENDS]. 02:22:30 [CLIP 3 BEGINS] Landau talks about the history of the Vaad Hatzala. He says it began as an orthodox organization to save the yeshivas in Eastern Europe and they in fact helped get members of many yeshivas in Lithuania visas to Shanghai via Russia. Vaad Hatzala later worked on rescuing all Jews, not just the orthodox. FILM ID 3146 -- Camera Rolls #154-158 Landau describes Weissmandel's work with Gisi Fleischmann, who as a woman and a leftist was altogether different from Weissmandel [CLIP 3 ENDS]. He describes Weissmandel's coded cables, with instructions to bomb certain cities, and the negative answers these demands received when they were transmitted to the Allies. Landau says that after the war Weissmandel still had hope that his wife and children had survived Auschwitz. [CLIP 4 BEGINS] He reads from a letter that was sent to Sternbuch by a relative from Warsaw and deciphers its coded contents for Lanzmann, as an example of how people had to communicate at the time. Landau talks about buying passports for people, which were sent to the ghettos or internment camps [CLIP 4 ENDS]. FILM ID 3147 -- Camera Rolls #149,151,159 -- 04:00:00 to 04:05:40 Mute. Landau praying at synagogue and looking through documents with Lanzmann. CUs of a diary in Hebrew and telegrams.

Leib Garfunkel - Ghetto Kovno

Film