Overview

- Brief Narrative

- German poster with an image of barley stalks overlaid on a swastika, and a religious-themed message, “Everything is due to God's blessing”. By 1934, when this poster was distributed, Germany was struggling to cope with the consequences of the Great Depression. Six million Germans were unemployed and struggled to obtain food. Organized religion, specifically the Protestant Church, was one of the main pillars of German society. The country had approximately 45 million Protestant Christians, 22 million Catholic Christians, 500,000 Jews, and 25,000 Jehovah’s Witnesses. The quotation on the poster exemplifies Germany’s religious and cultural values, while the imagery of the growing barley overlaid on the swastika implies the coming abundance the Nazi government would provide. The religious quote combined with the large swastika may also be an attempt to imply that Nazi rule and power is derived from God, which would absolve the party leadership from adhering to any man-made authority. The relationship between the Nazi party and religion was complex. Initially, the Party was not openly hostile to the Protestant and Catholic Churches; however, the Party believed that Christianity and Nazism were ideologically incompatible. In 1933, the Reich Church was established to advocate a form of Nazi Christianity that excluded the Old Testament, which was considered a Jewish document. The Nazi government also signed a Concordat with the Vatican, stating it would recognize the Nazi regime, which would in turn would not interfere in the Catholic Church. However, the Concordat was broken by the Nazis in 1935, with the passage of anti-religious policies, to undermine the church’s influence.

- Title

- An Gottes Segen ist alles gelegen

- Alternate Title

- Everything is due to God's blessing

- Date

-

publication/distribution:

1934

- Geography

-

publication:

Germany

- Credit Line

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection

- Markings

- front, printed, top and bottom, red and black ink : An Gottes Segen / ist alles gelegen [Everything is due to God's blessing]

front, bottom left, printed, black ink : No. 494

front, bottom right, within circle, printed, black ink : GD

Physical Details

- Language

- German

- Classification

-

Posters

- Category

-

Nazi propaganda

- Object Type

-

Posters, German (lcsh)

- Genre/Form

- Political posters.

- Physical Description

- Poster printed on discolored, tan paper. The poster has a large, black, canted swastika in the center. A golden-colored barley stalk with two thin, angled leaves is growing from the bottom of the poster. The three yellow barley heads growing from the stalk are overlaid on the swastika. The details of the stalk, leaves, and heads are shaded with reddish-brown tones. Above and below the image is large, red and black-colored German text in fraktur-style font. Small, black text is in the lower left corner, and a small logo is in the lower right. The entire image is surrounded by a thin, rectangular, black border. The paper has a white stain along the top edge, near the center.

- Dimensions

- overall: Height: 23.750 inches (60.325 cm) | Width: 17.750 inches (45.085 cm)

- Materials

- overall : paper, ink

: pencil - Inscription

- front, top left corner, handwritten, pencil : 2.0

Rights & Restrictions

- Conditions on Access

- No restrictions on access

- Conditions on Use

- No restrictions on use

Keywords & Subjects

- Topical Term

- Barley. Religion. Swastikas.

- Geographic Name

- Germany.

- Corporate Name

- Nazi Party

Administrative Notes

- Legal Status

- Permanent Collection

- Provenance

- The poster was acquired by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in 1990.

- Funding Note

- The cataloging of this artifact has been supported by a grant from the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany.

- Record last modified:

- 2023-06-01 09:16:00

- This page:

- https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn3752

Download & Licensing

In-Person Research

- By Appointment

- Request 21 Days in Advance of Visit

- Plan a Research Visit

- Request to See This Object

Contact Us

Also in German poster collection

The collection consists of anti-Semitic, advertising, and political posters, and a pair of shoes worn in Buchenwald concentration camp.

Date: 1932-1948

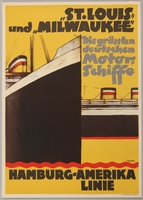

Poster advertising the flagships of the Hamburg-Amerika Line

Object

German advertisement poster for the Hamburg-America Line’s transatlantic liners, St. Louis and Milwaukee. On May 13, 1939, the St. Louis set sail from Hamburg, Germany with 937 passengers, almost all of whom were Jews fleeing the Third Reich. The majority of the passengers had applied for US visas, and planned to stay in Cuba until they could enter the United States. However, shortly before the ship set sail, Cuba invalidated the landing permits and transit visas of the Jewish refugee passengers. When the St. Louis arrived in Cuba on May 27, the Cuban government only allowed 28 passengers into the country. On June 2, the ship was ordered to leave Cuba. With 908 passengers still aboard, the St. Louis sailed to Miami, Florida where the Jewish refugees were again refused entry due to strict quota limits and isolationist sentiment. The St. Louis sailed back to Europe on June 6, 1939. Jewish organizations were able to secure entry visas for the passengers in Great Britain, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands rather than return to Germany. Of the 620 passengers who returned to continental Europe, 254 died in the Holocaust. Gustav Schroeder, the captain of the St Louis was recognized as Righteous Among the Nations on March 11, 1993 in acknowledgement of his efforts to find safe passage for his Jewish passengers.

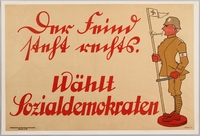

German Social Democratic Party anti-Nazi election poster

Object

German, anti-Nazi political propaganda poster promoting the Social Democratic Party for the elections of 1932. The figure on the poster wears the brown garb of a Sturmabteilung (SA or Storm Trooper), a paramilitary organization that had a reputation for violence and intimidation against Jews and Nazi opponents. By June 1932, Germany was deep in the throes of the Great Depression, with six million unemployed. This economic distress contributed to a rise in the popularity of the Nazi Party who along with the Communist Party and the Social Democrats, were the most popular political parties in Germany. The Social Democrats ran on a platform of maintaining freedom, democracy and the Republic, honoring Germany’s political and financial obligations, job creation, governmental expenditure cuts to lower taxes, and free speech. When Germany held parliamentary elections in July of that year, the Nazi party won almost 40 percent of the electorate in the Reichstag to become the largest party in German parliament. However, Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party failed to defeat incumbent Social Democratic President Paul von Hindenburg in the presidential election. With the backing of his majority party, Hitler was appointed Chancellor on January 30, 1933.

German Social Democratic Party election poster with a man smashing a swastika with a hammer

Object

German anti-Nazi political propaganda poster promoting the Social Democratic Party for the elections of 1932. The poster features a man smashing a swastika, the most recognizable icon of Nazi Party. By June 1932, Germany was deep in the throes of the Great Depression, with six million unemployed. This economic distress contributed to a rise in the popularity of the Nazi Party who along with the Communist Party and the Social Democrats, were the most popular political parties in Germany. The Social Democrats ran on a platform of maintaining freedom, democracy and the Republic, honoring Germany’s political and financial obligations, job creation, governmental expenditure cuts to lower taxes, and free speech. When Germany held parliamentary elections in July of that year, the Nazi party won almost 40 percent of the electorate in the Reichstag to become the largest party in German parliament. However Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party failed to defeat incumbent Social Democratic President Paul von Hindenburg in the presidential election. With the backing of his majority party, Hitler was appointed Chancellor on January 30, 1933.

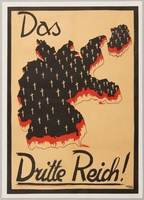

Social Democratic Party election poster depicting Germany as a graveyard

Object

Anti-Nazi political poster from the 1932 German federal elections. The poster depicts Germany bleeding and covered in crosses, implying if the Nazis gained power, their systems of violence and intimidation would cause Germany and its people to suffer. By June 1932, Germany was deep in the throes of the Great Depression, with six million unemployed. This economic distress contributed to a rise in the popularity of the Nazi Party who along with the Communist Party and the Social Democrats, were the most popular political parties in Germany. The Social Democrats ran on a platform of maintaining freedom, democracy and the Republic, honoring Germany’s political and financial obligations, job creation, governmental expenditure cuts to lower taxes, and free speech. When Germany held parliamentary elections in July of that year, the Nazi party won almost 40 percent of the electorate in the Reichstag to become the largest party in German parliament. However Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party failed to defeat incumbent Social Democratic President Paul von Hindenburg in the presidential election. With the backing of his majority party, Hitler was appointed Chancellor on January 30, 1933.

Nazi Party election poster with a man smashing a financial building with a battering ram

Object

Political poster promoting the Nazi Party and Adolf Hitler for the German election in Saxony on May 20, 1928. The poster is dominated by the image of a muscular worker demolishing the Saxon parliament building, which bears the label “International High Finance.” Though the theme of a worker destroying a government building was often used utilized by Communist groups, Nazi political groups also employed it to win the votes of the working class. During the 1920s, both Left-and-Right-wing groups in Germany opposed parliamentary rule. The destruction of a building associated with government and finance implied that Nazi leaders would be able to solve the many social problems plaguing Germany at the time. The nation was deep in the throes of the Great Depression, with six million unemployed. This economic distress contributed to a rise in the popularity of the Nazi Party who along with the Communist Party and the Social Democrats, were the most popular political parties in Germany. The Nazis supported economic nationalism and distrusted international capital, preferring domestic production with the elimination of foreign competition.

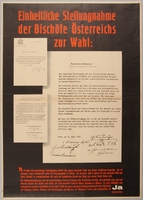

Poster expressing Austrian Bishops' support for Anschluss

Object

Poster displaying three typed letters written by Austrian Bishops and other Catholic clergy members expressing support for Anschluss, the German annexation of Austria in 1938. The letters are marked with the signature and seal of Theodore Innitzer, Archbishop of Vienna. Austria had experienced a prolonged period of economic stagnation, political dictatorship, and intense Nazi propaganda. When German troops entered the country on March 12, 1938 they received the enthusiastic support of most of the population, including the clergy, and Austria was incorporated into Germany the next day. The poster is an attempt to curry support for a referendum that would legitimize the annexation. In April, the German annexation was retroactively approved in a referendum that was manipulated by the Germans to indicate that about 99 percent of the Austrian people wanted the union.

Propaganda advertisement implying that Hitler supports equality and peace

Object

Nazi political poster from the 1930s with a quote from Adolf Hitler calling for equality and peace. The same phrase was used in Nazi election propaganda leading up to Germany’s November 12, 1933 parliamentary elections. The demand for equality refers to the vote on whether Germany would withdrawal from the League of Nations, which it would do in October of that year. The quote may have been reused after Germany annexed Austria in the Anschluss, when the Nazis held a referendum to legitimize their annexation.

War propaganda poster mapping German military conquests

Object

Propaganda map of Europe showing German territorial gains and offensive movements of its army, navy and air force against its enemies in 1942. By 1942 Germany had made alliances with Finland, Italy, Bulgaria and Hungary and had conquered France, Norway, and every European nation in Eastern Europe. The German invasion of the Soviet Union had pushed nearly into Moscow, Britain was fighting to maintain its presence in Africa and the Middle East, and the United States, who just entered the war in December 1941, had made no real impact as of yet. The map depicts Nazi Germany at the height of its domination over Europe.

Pro-Nazi election poster with a farmer using a pitchfork against the bourgeoisie

Object

Political campaign poster for the Reichstag elections of July 31, 1932, showing a muscular Aryan farmer with a swastika belt buckle, using a pitchfork to remove dwarfish caricatures of Nazi Party enemies. These parties are represented by former Chancellor of Germany Herman Müller, a caricature of a stereotypical Jewish businessman with a newspaper (the press) in his pocket, a businessman, and a communist. The Nazis blamed these groups for Germany’s loss in World War I, the failure of the Weimar Republic, and the economic depression that Germany was going through. The poster depicts the Nazis’ target demographic, a young, working class, Aryan man, disposing of the Nazis’ enemies, in essence, empowering the people to take Germany from the rich and powerful and return it to the hands of the farmers and working men.

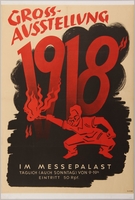

Anti-Bolshevist, Anti-Semitic 1918 Great Exhibition advertisement poster

Object

Poster showing a figure shaded in red with stereotypical Jewish features setting fire to the numbers 1918. It is a propaganda advertisement for the 1944 Grossausstellung 1918 Exhibition, which was designed to show Germans why they were fighting World War II. The Exhibition was title 1918 in order to emphasize that Germany surrendered that year and showed how horrible the conditions in Germany were at the conclusion of World War I. The imagery of a man with Jewish features, with both the year and him presented in red, strongly implies the Nazi belief that Jewish Communists sabotaged the German war effort and brought forth the inevitable consequences for Germany.

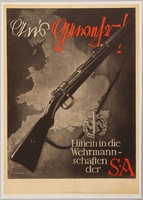

Black and white Sturmabteilung (SA) recruitment poster with a rifle over the British coastline

Object

German recruitment poster for the Sturmabteilung (SA), a Nazi paramilitary organization responsible for protecting party meetings, voter intimidation, and physically assaulting opponents. The wreath and sword symbol at the lower right are also featured on the SA sport badge and armband which were given out for physical accomplishment. As a result of the Great Depression and the growing popularity of the Nazi Party, SA membership swelled to 400,000 by 1932, and by 1933 membership was at approximately two million. On The Night of Long Knives, June 30, 1934, Hitler and the Schutzstaffel (SS) carried out a purge, murdering dozens of SA leaders including its cofounder and commander Ernst Röhm. Afterwards, the SA ceased to play a major role in Nazi affairs.

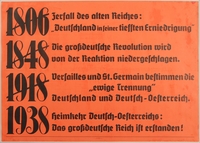

Text only poster declaring the Anschluss as a German Austria homecoming

Object

German text only poster declaring the German annexation of Austria, the Anschluss, as a long overdue homecoming for Austria. The poster highlights several important years and events in Austrian and German history. In 1806, France and Napoleon dissolved the Germanic Holy Roman Empire which had stood for nearly a thousand years, and created a French puppet state from the German kingdoms. The Revolutions of 1848 were a series of revolts against European monarchies that spread from France into Austria and the other German states. The revolts all ended in failure with the monarchies retaining their power. World War I ended in 1918 and the Treaties of Versailles and St. Germain were signed. The Allies placed the blame for the war on Germany and the Kingdom of Austria-Hungary and levied massive reparations against the two nations, forced them to cede territory, and broke up Austria Hungary into several smaller independent nations. Finally, in 1938, Germany annexed Austria, uniting the two German speaking peoples for the first time since the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire.

Waffen SS recruitment poster featuring a young uniformed soldier

Object

Recruitment poster for the Waffen SS featuring a profile image of a uniformed soldier. The Waffen SS was the armed military division of the Schutzstaffel (SS), the Nazi paramilitary organization that was responsible for security, intelligence gathering and analysis, and enforcing Nazi racial policies. They controlled the concentration camp system and planned and coordinated the Final Solution. The SS was originally formed in 1925 to protect Hitler along with other Nazi leaders and provide security at political meetings. In 1929, Heinrich Himmler was appointed Reichsführer-SS (Reich Leader of the SS) and turned the organization into an elite corps based on visions of racial purity and absolute loyalty to Hitler. The Waffen SS was established in 1939, eventually fielding more than twenty divisions and half a million men at its peak. The figure in the poster may have been based on Klemens Behler, who was an SS recruit at the time of the poster’s creation. He would go on to reach the rank of Obersturmbannführer (Senior assault unit leader) in the 23rd SS division, and was awarded the Knights Cross for his actions during the war.

Pro-Nazi election poster with the faces of Hitler and Hindenburg

Object

National Socialist German Workers' Party (Nazi Party) campaign poster featuring a black and white image of the heads of Adolf Hitler and Paul von Hindenburg. The quote below them is from poet Max von Schenkendorf and is inscribed on an 1897 monument to Kaiser Wilhelm I. The monument commemorates the founding of the German Empire and affirms German unity. The reuse of this quote, with its allusions to the monument and the German Empire, reaffirms the Nazi party platform of a union of all Germans. Forming a greater Germany through the abolition of the Treaty of Versailles and the return of lands lost in World War I was part of the Nazi Party platform. The image of Hitler’s face in front of Hindenburg’s and the text on the poster communicates that a reunion of German peoples and restoration of German national pride can only be accomplished through voting for Hitler and other Nazi Party candidates.

Pro-Nazi election poster featuring an oversized Aryan man towering over Germany’s enemies

Object

German poster for the 1932 Reichstag election showing a giant, muscular Aryan man looking down on dwarfish caricatures of the opposition candidates and German enemies. The poster features caricatures of former German chancellors Hermann Müller and Heinrich Brüning, as well as a figure wielding a bloody knife representing the threat of communism. A figure with stereotypical Jewish features and a newspaper in his pocket, denoting that the press is in the pocket of the Jews, is whispering in Müller’s ear, influencing his actions. Heinrich Brüning is holding a sign that references his use of emergency decrees and reliance on Section 48 of the Weimar Constitution during his term as chancellor from 1930-1932. The sign that the communist is holding shows their party’s interests are decidedly non-German, aligning with Russia and China. Müller’s sign implies that he and his Social Democratic Party work for the interest of the rich while the common man suffers.

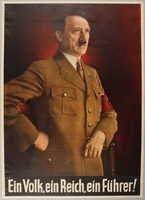

Color poster with a portrait of Hitler and the Nazi slogan: Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Führer!

Object

Color poster of an iconic painting of Adolf Hitler printed in Germany during the Third Reich, 1933-1945. The original painting was created by Heinrich Knirr in 1935-1936, and was based on a photograph taken by Heinrich Hoffman in 1935. Hitler approved the image and it became popular as it was widely used on Nazi propaganda pieces. The slogan Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Fuhrer (One People, One Country, One Leader) was one of the central slogans used by Hitler and the Nazi Party. Nazi propaganda portrayed their leader (Fuhrer) as the living embodiment of the German nation and people. This slogan reinforced the cult of Hitler and the sense of destiny that the Party claimed made him the savior of Germany and father of the German people.

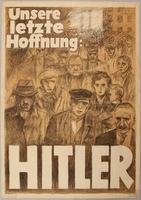

Pro Hitler poster featuring a crowd of forlorn people

Object

Poster for Adolf Hitler’s 1932 presidential campaign as the National Socialist German Workers' Party (Nazi Party) Presidential candidate against incumbent Paul von Hindenburg. This poster was designed by Hans Schweitzer, who went by the pseudonym Mjölnir (the hammer of Thor) and initially preserved by the FJM Rehse Archive and Museum of Contemporary History in Munich, a museum operated by the Nazi Party that preserved much of their early propaganda. By June 1932, Germany was deep in the throes of the Great Depression with six million unemployed. This economic distress contributed to a rise in the popularity of the Nazi Party who, along with the Communist Party and the Social Democrats, were the most popular political parties in Germany. This poster was designed to appeal to the unemployed and destitute and claimed that Hitler was their only hope. When Germany held parliamentary elections in July of that year, the Nazi party won almost 40 percent of the electorate in the Reichstag, becoming the largest party in German parliament. However, Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party failed to defeat Hindenburg in the presidential election. With the support of his majority party, Hitler was appointed Chancellor by Hindenburg on January 30, 1933.

Pro-Nazi election poster with a giant red swastika and number 1

Object

Political poster promoting the Nazi Party and Adolf Hitler for the German elections of 1932. The image shows how, with the people’s support, the Nazi Party became the most popular political party in Germany. This poster was initially preserved by the FJM Rehse Archive and Museum of Contemporary History in Munich, a museum operated by the Nazi Party that preserved much of their early propaganda. By June 1932, Germany was deep in the throes of the Great Depression, with six million unemployed. This economic distress contributed to a rise in the popularity of the Nazi Party who along with the Communist Party and the Social Democrats, were the most popular political parties in Germany. When Germany held parliamentary elections in July of that year, the Nazi party won almost 40 percent of the electorate in the Reichstag, becoming the largest party in German parliament. However Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party failed to defeat incumbent Social Democratic President Paul von Hindenburg in the presidential election. With the support of his majority party, Hitler was appointed Chancellor by President Hindenburg on January 30, 1933.

German propaganda poster featuring a gold eagle and Nazi flags

Object

German World War II propaganda poster featuring a golden eagle soaring in front of a series of Nazi flags created by artist Hans Schweitzer, who went by the pseudonym Mjölnir (Thor’s Hammer). The flag in the image is an interpretation of the Reichskriegflagge (German War Flag). It was designed personally by Hitler and was flown by all military forces of Nazi Germany. In 1943, the tide of the war had begun to turn against the Germans. The early progress of the invasion of the Soviet Union had stalled and the American and British armies had virtually pushed the German armies out of Africa. The Nazis used Nationalistic symbols such as the ones depicted on this poster to inspire the public and army to fight on.

Poster of Adolf Hitler and Konrad Henlein shaking hands after the annexation of the Sudetenland

Object

Poster depicting Adolf Hitler and Konrad Henlein shaking hands and promoting the German annexation of the Sudetenland. This image is a reproduction of a photograph of Hitler and Henlein’s meeting. In the original, Herman Goering is in the background but he has been edited out of this image. Czechoslovakia was founded in 1918 after the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian state at the end of World War I. Within its borders was the Sudetenland, an area with a predominantly German ethnic population. Konrad Henlein founded the Sudeten German Party, whose goal was to achieve autonomy for the Sudeten community so that they could unite their region with Germany. As the Nazi party gained power in Germany, Henlein and the Sudetenland reunification movement aligned with the party and transitioned from the fringes to a mainstream, and sometimes violent, political force. The Sudeten Nazis’ activities included hostile outbreaks and provocative incidents, and in September 1938 extreme violence erupted requiring international intervention. On September 30, representatives of France, Britain, Italy, and Germany met in Munich and issued an ultimatum to Czechoslovakia to cede the Sudetenland to Germany in exchange for a pledge of peace from Hitler. This poster was initially preserved by the FJM Rehse Archive and Museum of Contemporary History in Munich, a museum operated by the Nazi Party that preserved much of their early propaganda.

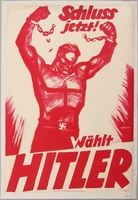

Pro-Nazi election poster of a giant worker breaking his shackles

Object

Political poster promoting Adolf Hitler for the German presidential elections of 1932. The poster features a man breaking chians on his wrists, implying that a vote for Hitler will stop the oppression that shackles the common man. Hitler ran as the National Socialist German Workers’ Party candidate against incumbent Paul von Hindenburg. This poster was designed by Hans Schweitzer, who went by the pseudonym Mjölnir (the hammer of Thor). By June 1932, Germany was deep in the throes of the Great Depression, with six million unemployed. This economic distress contributed to a rise in the popularity of the Nazi Party, who along with the Communist Party and the Social Democrats, were the most popular political parties in Germany. The Nazis supported economic nationalism and distrusted international capital, preferring domestic production with the elimination of foreign competition. When Germany held parliamentary elections in July of that year, the Nazi party won almost 40 percent of the electorate in the Reichstag, becoming the largest party in German parliament. However, Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party failed to defeat incumbent Social Democratic President Paul von Hindenburg in the presidential election. With the support of his majority party, Hitler was appointed Chancellor on January 30, 1933.

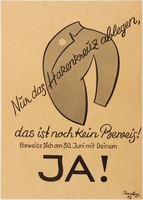

Poster encouraging the public to vote yes in the 1938 Anschluss referendum

Object

Anschluss poster displaying several arms raised for the Nazi salute in support of the Anschluss, the German annexation of Austria in 1938. Austria had experienced a prolonged period of economic stagnation, political dictatorship, and intense Nazi propaganda. When German troops entered the country on March 12, 1938 they received the enthusiastic support of most of the population, and Austria was incorporated into Germany the next day. The poster is an attempt to curry support for a referendum that would legitimize the annexation. On April 10, the German annexation was retroactively approved in a referendum that was manipulated by the Germans to indicate that about 99 percent of the Austrian people wanted the union. This poster was initially preserved by the FJM Rehse Archive and Museum of Contemporary History Munich, a museum operated by the Nazi Party that preserved much of their early propaganda.

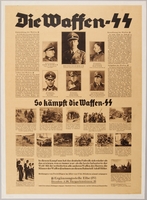

Waffen SS recruitment poster with multiple blocks of small text and photographs

Object

German recruitment poster for the Waffen SS featuring photographs of high ranking SS officers and soldiers participating in their wartime activities. The Waffen SS was the armed military division of the Schutzstaffel (SS), the Nazi paramilitary organization that was responsible for security, intelligence gathering and analysis, and enforcing Nazi racial policies. The SS controlled the concentration camp system and planned and coordinated the Final Solution. The SS was originally formed in 1925 to protect Hitler along with other Nazi leaders and provide security at political meetings. In 1929, Heinrich Himmler was appointed Reichsführer-SS (Reich Leader of the SS) and turned the organization into an elite corps based on visions of racial purity and absolute loyalty to Hitler. The Waffen SS was established in 1939 to strengthen the position of the SS relative to the army and German elites, eventually fielding more than twenty divisions and half a million men at its peak. Members of the Waffen SS were selected based on “racial” ancestry. Selected individuals were expected to have an Aryan Nordic lineage and volunteers were accepted from Germany, and later Norway, Denmark and Holland.

Waffen SS recruitment poster featuring a soldier and a Leibstandarte (SS Adolf Hitler flag)

Object

Recruitment poster for the Waffen SS featuring an image of a uniformed soldier and a Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler flag. The Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler was Hitler’s personal bodyguard regiment. The Waffen SS was the armed military division of the Schutzstaffel (SS), the Nazi paramilitary organization that was responsible for security, intelligence gathering and analysis, and enforcing Nazi racial policies. They controlled the concentration camp system and planned and coordinated the Final Solution. The SS was originally formed in 1925 to protect Hitler along with other Nazi leaders and provide security at political meetings. In 1929, Heinrich Himmler was appointed Reichsführer-SS (Reich Leader of the SS) and turned the organization into an elite corps based on visions of racial purity and absolute loyalty to Hitler. The Waffen SS was established in 1939 to strengthen the position of the SS relative to the army and German elites, eventually fielding more than twenty divisions and half a million men at its peak. Members of the Waffen SS were selected based on “racial” ancestry. Selected individuals were expected to have an Aryan Nordic lineage and volunteers were accepted from Germany, and later Norway, Denmark and Holland.

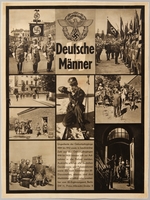

SS recruitment poster with photos depicting SS soldiers’ activities

Object

Recruitment poster for the Waffen SS featuring photographs of soldiers participating in their wartime duties. The Waffen SS was the armed military division of the Schutzstaffel (SS), the Nazi paramilitary organization that was responsible for security, intelligence gathering and analysis, and enforcing Nazi racial policies. They controlled the concentration camp system and planned and coordinated the Final Solution. The SS was originally formed in 1925 to protect Hitler along with other Nazi leaders and provide security at political meetings. In 1929, Heinrich Himmler was appointed Reichsführer-SS (Reich Leader of the SS) and turned the organization into an elite corps based on visions of racial purity with absolute loyalty to Hitler. The Waffen SS was established in 1939 to strengthen the position of the SS relative to the army and German elites, eventually fielding more than twenty divisions and half a million men at its peak. Members of the Waffen SS were selected based on “racial” ancestry. Selected individuals were expected to have an Aryan Nordic lineage and volunteers were accepted from Germany, and later Austria, Norway, Denmark and Holland.

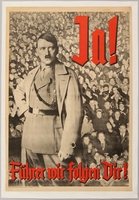

Nazi propaganda poster of Adolf Hitler in front of a mass of saluting people

Object

German political poster encouraging public support for Adolf Hitler’s usurpation of power after the death of German President, Paul von Hindenburg, in 1934. The poster features a photographic image that shows the public saluting and cheering Hitler, and text exclaiming their adoration, implying Germans’ united support for his assumption of power as sole leader of Germany. After Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933, he began laying the foundations for the Nazi state, worked to secure his power, and eliminate his opposition. In February 1933, after an attack on the Reichstag, the government passed the Reichstag Fire Decree, which suspended individual rights and due process of law. In March, 1933, the German Parliament passed the enabling act, which allowed Hitler to create and sign legislation into law without parliamentary consent. To eliminate their opposition, Hitler and the Nazis abolished trade unions, replaced elected officials with Nazi appointees, and outlawed other political parties. On June 30, 1934, the Schutzstaffel (SS), acting on orders from Hitler, executed the party’s political enemies and rival members who threatened Hitler’s rule. On August 2, the last barrier to Hitler’s total control of Germany, President Paul Von Hindenburg, died. Hitler ordered the government to merge his position of Chancellor with the office of the President. To legitimize his position, the Nazis declared a referendum take place on August 19. The Nazis campaigned heavily for public support of the referendum and 89 percent of voters supported the merger, approving Hitler’s absolute control of Germany.

Broadside proclaiming public support for the declaration of Hitler as both Chancellor and President

Object

German political broadside encouraging public support for Adolf Hitler’s usurpation of power after the death of German President, Paul von Hindenburg, in 1934. The broadside features an image of the ballot used in the referendum with the affirmative box brightly marked with a large X. After Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933, he began laying the foundations for the Nazi state, worked to secure his power, and eliminate his opposition. In February 1933, after an attack on the Reichstag, the government passed the Reichstag Fire Decree, which suspended individual rights and due process of law. In March of 1933, the German Parliament passed the enabling act, which allowed Hitler to create and sign legislation into law without parliamentary consent. To eliminate their opposition, Hitler and the Nazis abolished trade unions, replaced elected officials with Nazi appointees, and outlawed other political parties. On June 30, 1934, the Schutzstaffel (SS), acting on orders from Hitler, executed the party’s political enemies and rival members who threatened Hitler’s rule, in what would later be called, the Night of the Long Knives. On August 2, the last barrier to Hitler’s total control of Germany, President Paul Von Hindenburg, died. Hitler ordered the government to merge his position of Chancellor with the office of the President. To legitimize his position, the Nazis declared a referendum take place on August 19. The Nazis campaigned heavily for public support of the referendum, and 89 percent of voters supported the merger, approving Hitler’s absolute control of Germany.

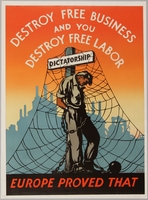

United States pro-free business and anti-dictatorship propaganda poster

Object

Anti-dictatorship, pro-free business poster featuring a man chained to a post, designed by Chester Raymond Miller in 1944, for the Think American Institute as part of the Think American Poster Series. The Think American Institute was formed by a group of industrialists from Rochester, New York, to combat subversive propaganda they felt was infiltrating American business. The group aimed to preserve the social order, boost American morale, extend the institutions of American freedom, and aid the war effort after the U.S. entry into World War II. The group was led by William G. Bromley, president of Kelly-Read & Company, and the lead designer Miller, who also served as the Art Director for Kelly-Read & Company. The Think American Series ran from 1939 to the early 1960s, and produced weekly posters with illustrated messages that were placed in financial, business, and educational organizations across America. The series produced over 300 poster designs during the war and more than 1,000 overall, with the majority conceived by Miller. A main theme of the series was the association of individual freedom with freedom of industry. During the war, this subtext was used to link Axis dictatorships to the subjugation of their citizens through the nationalization of business. The success of American private industry not only provided the tools to fight the war, but it also was an antithesis to Axis ideology. The Think American Institute repackaged and reused these themes after the war, in response to the Cold War and the threat of communism.

French collaborationist anti-Bolshevist propaganda poster

Object

French propaganda poster, published and distributed by the Centre d'études antibolcheviques (CEA, Center for anti-Bolshevik Studies) and the Office de répartition de l’affichage (ORAFF, Display Distribution Office) in German-occupied France between 1942 and 1944. The poster shows an image of two men fighting each other. One man, a physical manifestation of communist Bolsheviks, is bathed in red, a color traditionally associated with communism. The man also has stereotypically antisemitic Jewish features; a large, hooked nose, full lips, and pointed ears, which associate Jews with communists, both considered enemies by the Nazis. He wields a chain, a symbol of oppression, and attempts to wrap his opponent in it. The opponent is a shirtless man symbolizing Germany, struggling against communist Bolshevik subjugation. He (Germany) fights, according to the French caption, “for a free Europe.” In September 1939, following the German invasion of Poland, France and Britain declared war on Germany. In May 1940, Germany invaded and quickly overwhelmed French forces. In June, Marshal Henri Phillippe Petain signed an armistice agreement, granting Germany control of northern and western France, including Paris. After the armistice and occupation, German authorities and French collaborators began releasing propaganda to fuel resentment among the French public toward the Nazi’s enemies. The CEA was a French collaborationist organization created in 1942 to distribute propaganda vilifying the French Resistance, Communists, the British, and Jews. ORAFF was created by German authorities in 1941 to control and censor posters that did not comply with Nazi policy, and publicly display propaganda posters that conformed to Nazi ideals.

Nazi-era propaganda poster motivating the public to work

Object

German propaganda poster designed by Künstlerbund, Karlsruhe A.G. and published by Gaupropagandaleitung Baden der NSDAP (District Baden Propaganda Line of the NSDAP) in 1934. The poster was designed O. Rinne, possibly a pseudonym for German Art Deco artist, Felix Rinne. The poster shows an oversized man wearing the shirt, jodhpurs, and armband from a Nazi Sturmabteilung (SA) uniform preparing to confront a group of affluent men at a table decorated with a Nazi banner. He is rolling up his sleeves and getting ready to work, while the men are leisurely talking at the table instead of working. In addition to printing posters during World War II, Künstlerbund, Karlsruhe A.G. printed maps for the German military.

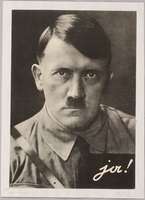

German election poster featuring a photographic portrait of Adolf Hitler

Object

German poster featuring a photorealistic, black and white image of Adolf Hitler wearing a Sturmabteilung (SA) uniform. The Sturmabteilung (SA) was a Nazi paramilitary organization responsible for protecting party meetings, voter intimidation, and physically assaulting opponents. As a result of the Great Depression and the growing popularity of the Nazi Party, SA membership swelled to 400,000 by 1932, and by 1933, membership was at approximately two million. On The Night of Long Knives, June 30, 1934, Hitler and the Schutzstaffel (SS) carried out a purge, murdering dozens of SA leaders including its cofounder and commander Ernst Röhm. Afterwards, the SA ceased to play a major role in Nazi affairs. The image is from a portrait of Hitler taken by his personal photographer, Heinrich Hoffmann. Images of Hitler from this photo session appeared in multiple forms of print media. Hoffmann joined the Nazi Party in 1920, and convinced an initially camera-shy Hitler of photography's political value. Hoffmann orchestrated and took photos of Hitler in public and private, and used the images to craft Hitler’s public image as a benevolent leader. Hoffmann’s photographs were published throughout Germany on postcards, stamps, posters, and books. Both Hitler and Hoffman profited financially from the royalties of the photos, and made millions of Reich marks. Hoffman’s assistant, Eva Braun, became Hitler’s mistress in 1930.

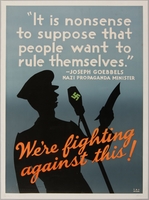

United States anti-Nazi poster of Joseph Goebbels reciting a speech

Object

Anti-Nazi poster using a supposed quotation from Joseph Goebbels to justify American involvement in World War II, designed by Chester Raymond Miller in 1944, for the Think American Institute (TAI) as part of the Think American Poster Series. The Think American Institute was formed by a group of industrialists from Rochester, New York, to combat subversive propaganda they felt was infiltrating American business. The group aimed to preserve the social order, boost American morale, extend the institutions of American freedom, and aid the war effort after the U.S. entry into World War II. The group was led by William G. Bromley, president of Kelly-Read & Company, and the lead designer, Miller, who also served as the Art Director for Kelly-Read & Company. The Think American Series ran from 1939 to the early 1960s, and produced weekly posters with illustrated messages that were placed in financial, business, and educational organizations across America. The series produced over 300 poster designs during the war and over 1,000 overall, with the majority conceived by Miller. Joseph Goebbels was a National Socialist politician and propagandist. He joined the Nazi Party in 1924 and rose swiftly through the ranks. When Hitler and the Nazis ascended to power in 1933, Goebbels took over the Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda. The ministry exerted control over film, radio, theater, and the press, and was responsible for promoting Nazi ideology and antisemitism.

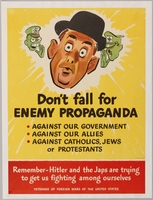

American propaganda poster with anti-Nazi and anti-Japanese caricatures

Object

American propaganda poster urging the public to be alert for enemy propaganda, designed by Jack Betts and distributed in 1943 by Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States (VFW). The poster uses the caricatured faces of Nazi dictator, Adolf Hitler, and Japanese emperor, Hirohito, whispering into a man’s ear as symbols of enemy propaganda reaching the American public. The poster warns the reader that enemy propaganda attempts to divide Americans and turn them against their government and each other. During the war, the government was concerned about the effects of German and Japanese propaganda on the American public. Radio was an important tool, and Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany used native English speakers to broadcast radio messages to the soldiers and the public, spreading disinformation and creating fear. Like the Avoid Careless Talk poster series created by the Office of War Information, it reminds the public of the vital part they play in the war effort. The VFW supported the war effort at home by creating posters, encouraging enlistments, raising money, and establishing an Aviation Cadet program to train and educate young pilots. Jack Betts was an American illustrator and artist who created advertising comics, and illustrations for magazines.

Satirical, Hitler wanted for murder poster

Object

Anti-Nazi propaganda poster distributed in the United States during World War II. The poster falsely claims that Adolf Hitler’s real name is Adolf Schicklgruber. An assertion which was originated by Hans Habe, a Viennese Jewish writer. The claim was based on the last name of Hitler’s father, who was born Alois Shicklgruber. Before Hitler was born, Alois changed his name and it became Alois Hitler. The motif of Hitler’s “real” name was likely an attempt to ridicule the leader and belittle him to the public. The Adolf Schicklgruber and Hitler "wanted for murder" motifs were also used on other ephemera, such as buttons. The poster was distributed by Fight for Freedom (FFF), an interventionist organization founded in April 1941. The FFF called for the United States to enter the war against Germany, and frequently coordinated with President Roosevelt’s aides, British propagandists, and other interventionist organizations to rally public support. The FFF told Americans the Axis powers were murdering civilians in the countries they occupied, and sponsored rallies to protest mass murders. After the United States entered the war, a wave of American patriotism and anti-Axis sentiment swept through the country. Much of this was manifested through pieces of ephemera such as posters, buttons, pins, cards, toys, and decals. This sentiment continued in America until the end of the war.

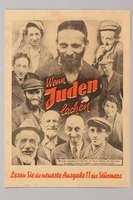

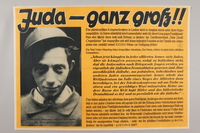

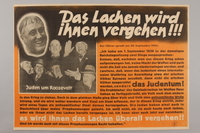

Antisemitic Der Stürmer advertising flier showing several Jewish people smiling

Object

Antisemitic, advertising flier for the Der Stürmer newspaper showing photographic images of the “devilish grins” of Jews. The text claims that Jews are born criminals, who are incapable of laughter, and can only smile nefariously, which implies their untrustworthy nature. Two versions of the flier were published: this one with red lettering and an advertisment on the bottom, and one with black-and-white text without a bottom advertisement. The antisemitic newspaper was founded by Julius Streicher and published from 1923 to 1945. Striecher used the paper as a platform to foment public hatred of the Jewish race. The paper blamed Jews for the depression, unemployment, and inflation in Germany as well as rape and other crimes against the German people. Der Stürmer also accused Jews of "blood libel" or "Jewish ritual murder" antisemitic fabrications that were common in the Middle Ages. They claimed that Jews used Christian blood, usually from children, obtained from a torturous ritual sacrifice to perform religious ceremonies. The paper often featured crude and distasteful cartoons that showed Jewish people as ugly, with exaggerated features and misshapen bodies. The paper became very popular, eventually reaching a circulation of 800,000. After the war ended, Streicher was arrested by the US Army in May 1945. He was tried by the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, convicted, and executed per the ruling that his repeated publication of articles calling for the annihilation of the Jewish race were a direct indictment to murder and a crime against humanity.

Antisemitic poster with an image of and poem about the Wandering Jew

Object

Nineteenth century antisemitic poster printed by C. Burckardt in Weissenburg, Germany (now Wissembourg, France) featuring an image and a poem by Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart about the Wandering Jew. Christian Schubart was an 18th century German poet and musician. The poster references the story of the Wandering Jew, a Jewish man (in some versions named Ahasuerus) who taunted Jesus on his way to be crucified. In response, Jesus said “I stand and rest, but you will go on,” dooming him to live until the end of the world or the second coming of Christ. The origin of the story is uncertain, although parts may have been inspired by biblical passages. Some versions name the wanderer Cartaphilus, and claim he was Pontius Pilate’s doorkeeper, who struck Jesus, urging him to go faster on the path to his crucifixion. The Ahasuerus version can be traced back to a German pamphlet published in 1602 which was translated into several languages and widely distributed. The story of the Wandering Jew has been portrayed and depicted in works of art, poetry, literature, plays, and films. In Schubart’s poem, the Jew is named Ahasver and he denies Jesus’ request for rest on the way to his crucifixion. As a result Ahasver is cursed to never die by an angel. Ahasver lives to see his loved ones die, cities and nations rise and fall, and bears mortal wounds that only cause him pain and suffering. In the end, the angel returns, and allows Ahasver to die, showing God’s mercy.

Pro-Nazi election poster of a man smashing a red and black block

Object

Political poster published by Hermann Esser and printed in Munich, Germany, promoting the Nazi Party candidates for a national election held between 1924 and 1933. The poster features an image of a tradesman smashing a black and red block with a hammer, while a swastika within a sun-like circle hovers over the horizon. The image implies that the people will smash the previous government, represented by the block depicted in two traditional colors of the German flag, while the Nazi party rises. Herman Esser, was a co-founder of the German Worker’s Party, and a prominent early Nazi Party member. He was the first chief of Nazi Party propaganda, however, his role in the party diminished, in part due to his unscrupulous personal life and antagonistic relationships with other prominent party members. The Nazis first entered candidates in German elections in 1924. However, they, did not have much success until 1930, when the party won 107 seats in Germany’s parliament, the Reichstag. In July 1932, the Nazi Party won 230 seats, and became the largest political party in the Reichstag. With the support of his majority party, Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor on January 30, 1933. In March, the final free election was held in the Weimar republic, and the Nazi Party won 288 seats in the Reichstag. Later that month, the cornerstone of Hitler’s dictatorship, the Enabling Act was passed. It allowed Hitler to enact laws, including ones that violated the Weimar Constitution, without approval of parliament or President von Hindenburg.

Poster for the Lenie Riefenstahl film, Olympia, about the 1936 Olympics

Object

Poster for the German propaganda sports film, “Olympia” (The Gods of the Stadium), about the 1936 Summer Olympics held in Berlin, released in April, 1938. The poster features a photographic image of German Olympic athlete Erwin Huber in a discus throwing stance. Huber participated in the 1928 and the 1936 games. The poster image is reproduced from a scene in the opening of the film. The stance is reminiscent of the Discobolus, an ancient Greek statue of a discus thrower, which symbolizes the Olympics and the athletic ideal. Nazi authorities used the games to promote an image of a new, strong, and united Germany to foreign spectators and journalists while masking the regime’s targeting of Jews and Roma (Gypsies), as well as Germany’s growing militarism. Germany fielded the largest team, 348 athletes, and won the most medals. The games were used to promote the myth of “Aryan” racial superiority, physical prowess, and symbolize that "Aryan" culture was the rightful heir of classical antiquity. Leni Riefenstahl, who directed “Triumph des Willens” (“Triumph of the Will”), shot at the 1934 Nuremberg Rally, was commissioned by the Nazis to produce a film about the Berlin games, which would also promote all these ideals. Riefenstahl made two films, “Olympia Part I: Festival of the Nations” and “Part II: Festival of Beauty" and combined them to create “Olympia.” Riefenstahl’s work pioneered numerous cinematographic techniques and won Best Foreign Film honors at the Venice Film Festival and a special award from the International Olympic Committee (IOC) for depicting the joy of sport.

Military Order Number 201 announcement poster issued by postwar Soviet occupation forces in Germany

Object

Poster announcing Military Order Number 201, issued by the Sowjetisch Militärverwaltung in Deutschland (Soviet Military Administration in Germany, SMAD) in August 1947. Order 201 announced the implementation of new guidelines for denazification policy in the Soviet occupied zone (SBZ). After the German surrender on May 8, 1945, Germany was divided into zones of occupation by the Allies. The Soviet zone encompassed the eastern part of Germany. On June 6, SMAD was established to administer and carry out military, political, and economic tasks in the SBZ. One of the principal tasks undertaken in every occupation zone was denazification. After the conclusion of the war, the Allies worked to cleanse Germany of all traces of Nazi ideology, institutions, and laws. Additionally, they removed Nazi party members from office or positions of responsibility in an effort to wipe out the Nazi party and its influence. In the SBZ, this process was carried out by several commissions and committees, and was also used as a means to consolidate Communist rule, nationalize industry and confiscate property for land reforms. Denazification was used to purge public officials and fill the positions with members of Communist Party of Germany (KPD), which later became the Socialist Unity Party (SED), the ruling party of East Germany. However, many former Nazis were allowed to keep their positions so long as they conformed to Communism. By the 1950s, denazification efforts ended and many former Nazis were able to return to their former roles in industries and government in both East and West Germany.

Postwar East German "vote yes" poster on a public referendum

Object

Poster encouraging the German public of the Soviet-occupied region of Saxony to vote "yes" on a referendum to expropriate factories and companies owned by Nazis. The poster was designed by Wilhelm Schubert, who worked with the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), and distributed in May 1946. The poster implies that voting "yes" to the referendum will help to ensure peace in occupied East Germany. On June 30, the referendum passed, with 82.9 percent voting in favor. After the German surrender on May 8, 1945, Germany was divided into zones of occupation by the Allies. The Soviet zone encompassed the eastern part of Germany. On June 6, SMAD was established to administer and carry out military, political, and economic tasks in the Soviet occupied zone (SBZ). One of the principal tasks undertaken in every occupation zone was denazification. After the conclusion of the war, the Allies worked to cleanse Germany of all traces of Nazi ideology, institutions, and laws. Additionally, they removed Nazi party members from office or positions of responsibility in an effort to wipe out the Nazi party and its influence. In the SBZ, this process was carried out by several commissions and committees, and was also used as a means to consolidate Communist rule, nationalize industry and confiscate property for land reforms. Denazification was used to purge public officials and fill the positions with members of Communist Party of Germany (KPD), which later became the Socialist Unity Party (SED), the ruling party of East Germany. However, many former Nazis were allowed to keep their positions so long as they conformed to Communism. By the 1950s, denazification efforts ended and many former Nazis were able to return to their former roles in industries and government in both East and West Germany.

Postwar campaign poster encouraging Germans to vote on June 30, 1946

Object

Poster encouraging Germans to vote on June 30, designed by Barlog in 1946. The vote on June 30 is likely referring to the Bavarian state election in June 1946, to choose members of the Bavarian Constituent Assembly. After the German surrender on May 8, 1945, Germany was divided into zones of occupation by the Allies. The American-occupied zone encompassed the southeastern part of Germany, including Bavaria. The American goals during the occupation included denazification and the reintroduction of democratic values into German society. Denazification was a postwar Allied initiative to cleanse Germany of all traces of Nazi ideology, institutions, and laws. They also sought to remove Nazi party members from office or positions of responsibility in an effort to wipe out the Nazi party and its influence. In the American zone, anyone who had been an active Nazi, and individuals who held key positions in the regime were fired. In the summer if 1945, German political parties were reformed, and the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (Social Democratic Party, SPD) and the Kommunistiche Partei Deutschlands (German Communist Party, KPD), left-leaning parties that existed during the Weimar Republic reemerged. They were joined by the new Christlich-Demokratische Union (Christian Democratic Union, CDU) a more moderate party. These three parties became the largest in Germany. The Bavarian Constituent Assembly election on June 30, 1946, was the first free election held in Bavaria since 1932. Although denazification was labeled as a success, by the 1950s, many former Nazis were able to return to their roles in industries and government in both East and West Germany.

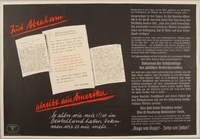

Antisemitic poster denouncing claims of Jewish persecution by Germany

Object

German propaganda poster likely issued the week of December 8, 1938, from the Parole der Woche (Word of the Week) series. The poster depicts letters allegedly written by a German-Jewish émigré in America, Abraham Reis, to his father, Simon Reis in Germany. The poster asserts that the letters reveal that Jews are lying about German persecution. The poster also claims that American Jews proposed plots to kill Adolf Hitler. The Nazis used propaganda to buttress public support for the war effort, shape public opinion, and reinforce antisemitic ideas. As part of their propaganda campaign, the Nazis created the Word of the Week Series of posters (also referred to as Wandzeitung, or wall newspapers), the first of which was distributed on March 16, 1936. Each week, approximately 125,000 posters were strategically placed in public places and businesses such as: market squares, metro stations, bus stops, payroll offices, hospital waiting rooms, factory cafeterias, schools, hotels, restaurants, post offices, train stations, and street kiosks so that they would be viewed by as many people as possible. Posters were the primary medium for the series, but smaller pamphlets were also produced, which could be plastered on the back of correspondence. The posters used colorful, often derogatory caricatures, and photorealistic images with vibrant language to target the Nazis’ early political adversaries, Jews, Communists, and Germany’s enemies during the war. The series was discontinued in 1943.

Nazi propaganda poster denouncing the United States for criticizing Germany's Jewish policies

Object

German propaganda poster, likely issued the week of January 19 to January 25, 1939, from the Parole der Woche (Word of the Week) series. This poster depicts a picture of Bishop Stephan Donahue, an auxiliary bishop of the Catholic Archdiocese of New York. Donahue was one of several American religious leaders to openly rebuke the Nazis for their persecution of Jews and other groups. The German text criticizes the United States for its discrimination against African and Asian Americans, and implies that Donahue is a hypocrite for not rebuking these policies as well. The text also reminds the reader of the antisemitic myth of Jewish deicide, the belief that Jews are collectively responsible for Christ’s death, and implies that the views of Donahue and the American Catholic leaders may be influenced by Jews. The relationship between the Nazi party and religion was complex. Initially, the Party was not openly hostile to the Protestant and Catholic Churches; however, the Party believed that Christianity and Nazism were ideologically incompatible. The Nazi government signed a Concordat with the Vatican, stating it would recognize the Nazi regime, which would in turn would not interfere in the Catholic Church. However, the Concordat was broken by the Nazis with the passage of anti-religious policies to undermine the church’s influence in 1935. The first Word of the Week Series of posters (also referred to as Wandzeitung, or wall newspapers), were distributed on March 16, 1936. The series used colorful, often derogatory caricatures, and photorealistic images with vibrant language to target political adversaries, Jews, Communists, and Germany’s enemies during the war. The series was discontinued in 1943.

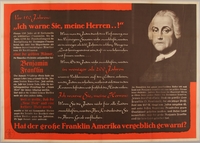

Antisemitic poster featuring supposed warnings about Jews from Benjamin Franklin

Object

German propaganda poster issued in 1939 from the Parole der Woche (Word of the Week) series. This poster shows excerpts from the Franklin Prophecy, an antisemitic speech falsely attributed to Benjamin Franklin, one of the founding fathers of the United States. Franklin is one of the most respected historical figures in the US, who helped write the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution. The first publication of the speech was on February 3, 1934, in “Liberation,” a paper published by William Dudley Pelley, a Nazi sympathizer and founder of The Silver Shirts. The group was aligned with the German-American Bund. According to the speech, Franklin believed that Jews were morally and commercially corrupt, and if allowed, would stream into the country and do nothing but leach off society. The speech was quickly debunked as a fraud by the Franklin Institute, the International Benjamin Franklin Society, and distinguished American historian, Charles Beard. However, the speech paralleled Nazi beliefs and was widely distributed over the radio, in writing, and was cited in speeches by Nazi leaders. The first Word of the Week Series of posters (also referred to as Wandzeitung, or wall newspapers), were distributed on March 16, 1936. Each week, new posters were placed in public places and businesses to be viewed by as many people as possible. Posters were the primary medium for the series, but smaller pamphlets which could be plastered on the back of correspondence, were also produced. The posters targeted the Nazis’ early political adversaries, Jews, Communists, and Germany’s enemies during the war. The series was discontinued in 1943.

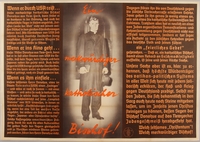

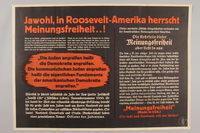

German poster accusing the United States of unfairly censuring figures critical of Jews

Object

German propaganda poster issued in 1939, from the Parole der Woche (Word of the Week) series. The poster references America’s Freedom of Speech and accuses the United States of censuring voices critical of Jews. As proof, the poster claims that Father Charles Coughlin, an extremist, antisemitic radio personality during the 1930s was unfairly censured for his broadcasts attacking Jews. The text then compares father Coughlin to George Mundelein, the Archbishop of Chicago, and a critic of Adolf Hitler and the Nazis, saying that he is allowed to speak because he is subservient to the Jews. The poster also falsely implies that US President Franklin Roosevelt is being influenced by Jews. In reality, Coughlin was ordered off the air by his superiors within the church, and was being investigated for denouncing America’s entry into World War II following the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. The Nazis used propaganda to buttress public support for the war effort, shape public opinion, and reinforce antisemitic ideas. As part of their propaganda campaign, the Nazis created the Word of the Week Series of posters (also referred to as Wandzeitung, or wall newspapers), which began distribution on March 16, 1936. Each week, new posters were placed in public places and businesses to be viewed by as many people as possible. Posters were the primary medium for the series, but smaller pamphlets which could be plastered on the back of correspondence, were also produced. The posters targeted the Nazis’ early political adversaries, Jews, Communists, and Germany’s enemies during the war. The series was discontinued in 1943.

Antisemitic poster concerning Jews in allied armies

Object

German propaganda poster issued in 1940, from the Parole der Woche (Word of the Week) series. The poster references Jews fighting for the British army and frames it as an act of desperation by the British. The yellow background color is a similar shade as the Star of David badges Jews were forced to wear in Germany. The poster shows an image of a captured Polish-Jewish soldier, attempting to make Jews appear inept as soldiers. Approximately 100,000 Jews fought in the Polish army against the invading German Army. At the outbreak of the war, Jewish leaders in Britain and Palestine campaigned for an official Jewish unit in the British Army. Meanwhile, approximately 30,000 Jews volunteered for service in the army. The Jewish Brigade formed in September 1944, and fought German forces in Italy. Overall, approximately 1.5 million Jews fought in Allied armies, and hundreds of thousands received citations for combat and bravery. The Nazis used propaganda to buttress public support for the war effort, shape public opinion, and reinforce antisemitic ideas. As part of their propaganda campaign, the Nazis created the Word of the Week Series of posters (also referred to as Wandzeitung, or wall newspapers), which began distribution on March 16, 1936. Each week, new posters were placed in public places and businesses to be viewed by as many people as possible. Posters were the primary medium for the series, but smaller pamphlets were also produced. The posters targeted the Nazis’ early political adversaries, Jews, Communists, and Germany’s enemies during the war. The series was discontinued in 1943.

German propaganda poster mocking British defeats and criticizing politician Duff Cooper

Object

German propaganda poster issued in 1940, from the Parole der Woche (Word of the Week) series. The poster references British politician Duff Cooper, who was Secretary of State for War in Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s administration. Cooper believed that Hitler and Nazi Germany were a threat to European peace, and used his position to fight for increased military budgets and rearmament. His views went against those of Chamberlain’s administration and public sentiment at the time. He was viewed by many as increasingly hawkish, and along with Winston Churchill and Anthony Eden, Cooper was called a warmonger by Hitler. Cooper disagreed with Chamberlain’s appeasement policy toward Hitler. After Chamberlain conceded Czechoslovakia to Germany in the Munich Agreement, Cooper resigned from office in protest. When Winston Churchill became Prime Minister, Cooper served as Minister of Information and as the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. The poster also references British defeats during the battles of France and Norway in 1940. The Nazis used propaganda to buttress public support for the war effort, shape public opinion, and reinforce antisemitic ideas. As part of their propaganda campaign, the Nazis created the Word of the Week Series of posters (also referred to as Wandzeitung, or wall newspapers), which began distribution on March 16, 1936. Each week, new posters were placed in public places and businesses to be viewed by as many people as possible. Posters were the primary medium for the series, but smaller pamphlets were also produced, which could be plastered on the back of correspondences. The posters targeted the Nazis’ early political adversaries, Jews, Communists, and Germany’s enemies during the war. The series was discontinued in 1943.

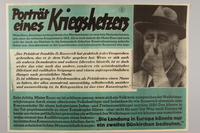

Nazi propaganda poster criticizing Franklin Roosevelt and American interventionist efforts

Object

German propaganda poster issued in 1941 from the Parole der Woche (Word of the Week) series. The poster references United States Secretary of the Navy, William Franklin "Frank" Knox, calling him a warmonger, likely because he advocated for support of the Allies before the U.S. entry into World War II (1939-1945). Knox, a former political rival of Roosevelt, was appointed as Secretary of the Navy in 1940, to encourage bipartisan support. The poster attempts to frame U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt, as a power hungry leader by using a supposed quote about the President by Knox. The text claims that President Roosevelt is a servant of the Jews, and American intervention in the war would lead to disaster for the U.S. The Nazis used propaganda to buttress public support for the war effort, shape public opinion, and reinforce antisemitic ideas. As part of their propaganda campaign, the Nazis created the Word of the Week Series of posters (also referred to as Wandzeitung, or wall newspapers), which began distribution on March 16, 1936. Each week, new posters were placed in public places and businesses to be viewed by as many people as possible. Posters were the primary medium for the series, but smaller pamphlets were also produced, which could be plastered on the back of correspondences. The posters targeted the Nazis’ early political adversaries, Jews, Communists, and Germany’s enemies during the war. The series was discontinued in 1943.

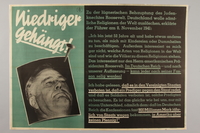

German propaganda poster claiming Hitler and the Nazis are not against religion

Object

German propaganda poster, issued the week of December 3 to December 9, 1941, from the Parole der Woche (Word of the Week) series. The poster shows an unflattering picture of United States President Franklin Roosevelt. The German text claims that Roosevelt is a Jewish puppet that said that the Nazis wish to destroy all religion. To refute this, the poster quotes a speech Adolf Hitler gave on November 8, 1941, at Löwenbräukeller in Munich, Germany, to commemorate the anniversary of the Beer Hall Putsch. In the speech, Hitler claims that he does not care what religion a person is. He goes on to falsely claim that religious leaders in the U.S. are barred from speaking out against the state, and that soldiers cannot attend religious ceremonies. The relationship between the Nazi party and religion was complex. Initially, the Party was not openly hostile to the Protestant and Catholic Churches; however, the Party believed that Christianity and Nazism were ideologically incompatible. The Nazi government signed a Concordat with the Vatican, stating it would recognize the Nazi regime, which would in turn would not interfere in the Catholic Church. However, the Concordat was broken by the Nazis with the passage of anti-religious policies to undermine the church’s influence in 1935. The first Word of the Week Series of posters (also referred to as Wandzeitung, or wall newspapers), were distributed on March 16, 1936. The series used colorful, often derogatory caricatures, and photorealistic images with vibrant language to target political adversaries, Jews, Communists, and Germany’s enemies during the war. The series was discontinued in 1943.

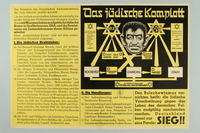

Nazi propaganda poster exposing the Jewish conspiracy links to the Allied Nations

Object

German propaganda poster issued during the week of December 10 to December 16, 1941, from the Parole der Woche (Word of the Week) series. The poster contains a diagram that maps out the alleged power structure and key Jewish figures that controlled the Nazi’s enemies. The accompanying text elaborates on the diagram. It gives brief backgrounds of the key figures, and shows their interconnectedness as well as their familial relationships with world leaders. The antisemitic myth that Jews use their power and influence to manipulate and control world governments is one of the most prevalent and long-lasting antisemitic conspiracy theories. Popularized with the widespread publication of the fabricated, antisemitic text, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the canard was a key component in Nazi ideology. Propaganda propagating the hoax was widely distributed throughout German territories. The Nazis used propaganda to buttress public support for the war effort, shape public opinion, and reinforce antisemitic ideas. As part of their propaganda campaign, the Nazis created the Word of the Week Series of posters (also referred to as Wandzeitung, or wall newspapers), which began distribution on March 16, 1936. Each week, new posters were placed in public places and businesses to be viewed by as many people as possible. Posters were the primary medium for the series, but smaller pamphlets were also produced, which could be plastered on the back of correspondences. The posters targeted the Nazis’ early political adversaries, Jews, Communists, and Germany’s enemies during the war. The series was discontinued in 1943.

German propaganda poster claiming the United States Army is using criminals to fight in Germany

Object

German propaganda poster issued during the week of June 17 to June 23, 1942, from the Parole der Woche (Word of the Week) series. The poster depicts pictures of American criminals from the recent past, including: Al Capone, Thomas Pendergast, Robert Emmet O'Malley, Robert J. Boltz, and William P. Buckner. The text purports that United States President Franklin Roosevelt recruited criminals to serve in the American armed forces against Germany. It also accuses Roosevelt of being a money launderer, and claims he has a rapport with the criminal elements. The Nazis use this unfounded appraoch as evidence that America’s war on Germany is unjust and ignoring that Germany declared war on the U.S. The poster also attempts to justify the Nazi’s treatment of Jews by showing a captioned picture of a man called, “Louis the rabbi” along with the criminals, and claims that Jews are in league with organized crime. The Nazis used propaganda to buttress public support for the war effort, shape public opinion, and reinforce antisemitic ideas. As part of their propaganda campaign, the Nazis created the Word of the Week Series of posters (also referred to as Wandzeitung, or wall newspapers), which began distribution on March 16, 1936. Each week, new posters were placed in public places and businesses to be viewed by as many people as possible. Posters were the primary medium for the series, but smaller pamphlets were also produced, which could be plastered on the back of correspondences. The posters targeted the Nazis’ early political adversaries, Jews, Communists, and Germany’s enemies during the war. The series was discontinued in 1943.

Antisemitic Nazi propaganda poster declaring that Jews are the enemy of the German people

Object

German propaganda poster issued during the week of July 1 to July 7, 1942, from the Parole der Woche (Word of the Week) series. The slogan in the title is an idiomatic phrase similar in meaning to the English saying "a leopard can't change its spots." The yellow background color is a similar shade as the Star of David badges Jews were forced to wear in Germany and German-occupied nations. This poster calls Jews enemies of the people and claims that Joseph Hertz, Chief Rabbi of the United Kingdom, declared that Jews were committing crimes against England’s war economy. The poster then accuses Jews of pushing nations into wars, and profiting from them at their nation’s expense. These new antisemitic stereotypes were proliferated in a defeated Germany after World War I (1914-1918). At the end of the war, the German public was unaware of the country’s faltering position and many believed Germany was winning. After surrender, it was said that the war was started and sabotaged by Jews with the goals of enriching themselves and creating a political climate more susceptible to Jewish control. These myths were seized- upon and distributed widely in Nazi ideology and propaganda, and used as a justification for Jewish persecution. The Nazis used propaganda to buttress public support for the war effort, shape public opinion, and reinforce antisemitic ideas. As part of their propaganda campaign, the Nazis created the Word of the Week Series of posters (also referred to as Wandzeitung, or wall newspapers), which began distribution on March 16, 1936. Each week, new posters were placed in public places and businesses to be viewed by as many people as possible. Posters were the primary medium for the series, but smaller pamphlets were also produced, which could be plastered on the back of correspondences. The posters targeted the Nazis’ early political adversaries, Jews, Communists, and Germany’s enemies during the war. The series was discontinued in 1943.

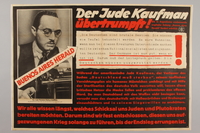

Nazi propaganda poster claiming American Jews want to exterminate the German people

Object

German propaganda poster issued during the week of August 19 to August 25, 1942, from the Parole der Woche (Word of the Week) series. This poster uses a quote from Theodore Kaufman’s book, “Germany Must Die,” and claims that the Jews and their allies are fighting to exterminate the German people. Theodore Kaufman was a fringe, Jewish-American extremist writer who advocated for the sterilization of German men and women as a means to eliminate the German people, and the partition of German territory among neighboring nations. Although his writings were not popular in America, the Nazis used them heavily in their propaganda to advocate for public support for the war. They falsely claimed that Kaufman’s ideas were popular opinion in America, and that Kaufman was an associate of President Roosevelt. The Nazis used propaganda to buttress public support for the war effort, shape public opinion, and reinforce antisemitic ideas. As part of their propaganda campaign, the Nazis created the Word of the Week Series of posters (also referred to as Wandzeitung, or wall newspapers), the first of which was distributed on March 16, 1936. Each week, approximately 125,000 posters were strategically placed in public places and businesses so that they would be viewed by as many people as possible. Posters were the primary medium for the series, but smaller pamphlets were also produced, which could be plastered on the back of correspondences. The posters used colorful, often derogatory caricatures, and photorealistic images with vibrant language to target the Nazis’ early political adversaries, Jews, Communists, and Germany’s enemies during the war. The series was discontinued in 1943.

German antisemitic poster alleging Roosevelt's Brain Trust is comprised of Jews

Object